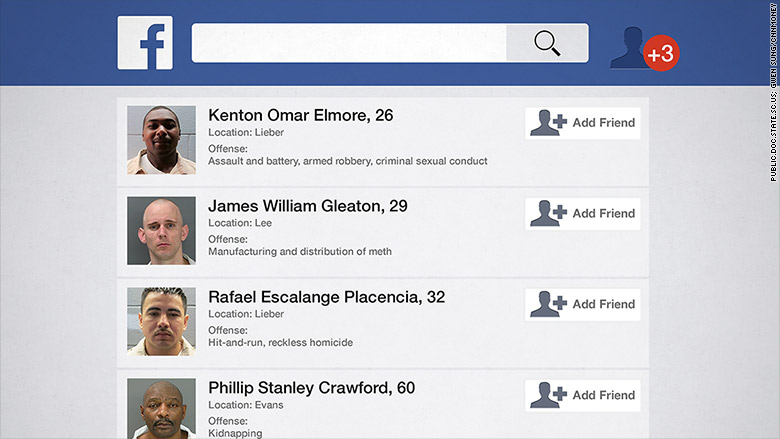

South Carolina prisoners get the harshest in-prison punishment -- solitary confinement -- just for using Facebook.

A report released Thursday by Electronic Frontier Foundation researcher Dave Maass shows that South Carolina's Department of Corrections considers "creating and/or assisting with a social networking site" while in prison an offense akin to committing a violent crime against another prisoner or officer.

Prisoners found to post on Facebook in South Carolina's system can face losing privileges such as visitation rights and telephone access, and many receive solitary confinement sentences, state documents show.

Punishments are doled out separately for each day that an inmate posts on a social networking site, such as Facebook or Twitter. That means posting once on Monday and once again on Wednesday counts as two individual violations, but posting 50 times on a single day counts as just one violation.

Over the past three years, 432 disciplinary cases have been brought against 397 South Carolina inmates for using social networks (mostly Facebook). Of those disciplined prisoners, 40 received more than two years in solitary confinement, and 16 were sentenced to more than a decade alone in a cell.

One inmate, Tyheem Henry, received a 37-year solitary confinement sentence for posting on Facebook 38 times. He also lost 74 years worth of phone, visitation and canteen rights.

Of the three prisoners who received more than two decades of solitary confinement, none will be able to serve their full punishment -- their sentences are all up before 2025.

They likely wouldn't have spent all that time in solitary confinement anyway. As a result of such long sentences, the South Carolina Department of Corrections has been forced to suspend punishments due to a lack of solitary confinement cells.

Just last week, the state began to roll back its use of solitary confinement as punishment for social media use. It will eventually cap time alone at 60 days -- and inmates can be let out early with good behavior.

South Carolina Corrections Department Director Bryan P. Stirling said he's dialing back, because he recognizes the severity of the punishment. He asserts that inmates don't deserve social media access. And even if they did, officers have too few resources to monitor Facebook usage to make sure inmates aren't stirring up trouble. So, he must equate unmonitored social media use via contraband cell phones as a potential threat to people's safety.

"Any hole in the system -- and social media is a hole into the system -- is a way for them to continue their criminal ways," he said. "There needs to be a punishment that's worse than, 'No candy for you today,' or, 'You won't see your mother.' There has to be something more severe than that."

Most prisons generally forbid inmates from using social media like Facebook (FB) and Twitter (TWTR), though South Carolina's punishments are particularly extreme.

Meanwhile, Facebook allows law enforcement officers to issue "inmate account takedown requests," preventing inmates from having a social media presence -- even disallowing friends or loved ones from posting on their behalf.

"They're acting like a censor. They don't have to do this," EFF researcher Dave Maass told CNNMoney.

In its defense, Facebook noted it's only following strict company rules that preclude others from signing into your account.

"Accessing Facebook from prison does not violate our terms, but allowing another person to access your account on your behalf does," a Facebook spokesman said.

The company said it will block accounts "when we believe they have been compromised for any reason, including in the case of people who are incarcerated and don't have Internet access."

"There's no U.S. law that requires Facebook to take down these pages," said David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union's national prison project. "We need to ask why Facebook is helping the government carry out its censorship agenda."

It's worth noting that, despite their crimes, inmates retain the right to free speech. They can write physical letters. They can make phone calls. Some even have websites.

Then again, a presence on social media is remarkably different from having a website. In many ways, digital playgrounds like Facebook are mere extensions of our physical neighborhoods.

Christine Ward, executive director of crime victim support network iCAN, worries about inmates on Facebook making veiled threats or directing gangs outside prison walls.

"We've dealt with inmates who've been stalking their victims from prison," she said. "It's not about free speech. It's about the safety of our community and others. You lose some privileges when you go to prison."

In documents obtained by EFF, South Carolina prison guards say they spotted one inmate posting photos of himself throwing signs "related to the Gangster Disciple gang." Another was "checking out" the prison nurse on Facebook. And another guy just had his mom make posts on his behalf.