We have tech solutions to address everything from cybercrime to health -- so why not diversity?

That question was the impetus for Unitive, a software startup founded by computer scientist Laura Mather.

Most employers wouldn't think twice about using words like confident or decisive in job descriptions, but in fact, those terms can discourage women from even applying.

So do words like "ninja," "fast-paced environment," "work hard, play hard" -- and "Silicon Valley."

"[They] project a 'brogrammer' culture," said Mather.

She's no newbie to solving problems in the tech world. She worked as a research mathematician at the NSA, followed by fraud defense at eBay (EBAY). In 2008 -- before cybersecurity was on the tip of everyone's tongue -- she launched cybersecurity firm Silver Tail, which raised $20 million from Andreessen Horowitz.

Mather's idea to solve diversity issues with technology was met with skepticism.

"80% of people [I talked to] said that's not possible," said Mather. "We should be embarrassed because we use technology to address everything."

So she developed software to root out unconscious bias in hiring decisions. For instance, a manager might be predisposed to hire someone who looks like the person who last filled the role.

Unitive's software uses years of research to eliminate unconscious biases like that.

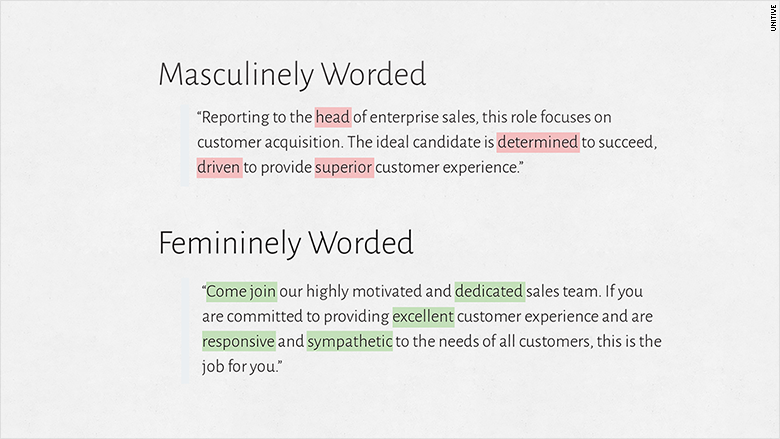

Certain words are more masculine (competitive, confident, determined, decisive and outspoken are a few common ones), others are deemed feminine (cooperative, honest, interdependent, loyal, understanding).

To improve diversity, companies need to be conscientious about balancing masculine-gendered terms in a job description with feminine-gendered ones.

The software underlines words in red if they should be reconsidered and links to the appropriate research so users can learn why the words are flagged. There are currently over 400 words (both problematic and inclusive) in the database.

Related: Can reality TV help tech's diversity problem?

It's not just about neutralizing the language: A McKinsey study found women only apply for jobs if they fit all the criteria, whereas men respond if they meet just 60%.

"The good news is: White men still apply," said Mather. "They're not turned off by inclusive words."

Mather demoed the software -- a recruiting and hiring suite that will be released in April -- at CNNMoney last month. Its user-friendly interface lets recruiters build job descriptions, review resumes and develop interview questions -- all in the system.

The software also asks employers to rank which qualities are most important in a candidate. That way, unconscious bias doesn't slip in.

"At the moment when [bias] is affecting our decisions, we don't feel like [it is]. It feels to us like we're making a decision on the merits," said Keith Payne, associate professor at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who Mather consulted in developing Unitive. "[A lot of people] are sincerely trying to do the right thing but are nonetheless showing systematic bias."

The resume review portion of the software separates a candidate's education from their experience -- which stems from a personal frustration. Mather said she applied to Google (GOOG) in 2006 and was told by the recruiter, "Larry Page looked at your resume and your experience is fantastic, but you didn't go to an Ivy League school so he's pretty concerned that you're not going to do well here." She was offered the job but declined it. "I had been out of school for 12 years," she told CNNMoney.

Mather sees many parallels with how companies viewed cybersecurity seven years ago and the way most address hiring today.

"In 2008 in security, the big realization was that we could no longer do things manually," said Mather, who sold Silver Tail for "hundreds of millions" of dollars to EMC (EMC) in 2012.

Improving diversity in hiring is similarly switching to automatic detection methods -- a market potentially worth $600 million, according to Deloitte.

"Before I even started, I was getting calls with people saying, 'How much would you charge us?'" Mather said, noting that she'll charge enterprise customers "six figures per year."

"The companies that invest in this now are going to be ahead profit-wise, innovation-wise," she said.

"And they probably aren't going to have as many lawsuits."