Greece has edged closer to default and possible exit from the eurozone after opting to postpone its 300 million euro ($337 million) payment to the International Monetary Fund.

But somehow, the prospect of Greece dropping out of the euro is not freaking out global markets as much as it once did.

Here is why a Grexit, while undoubtedly painful, might be much less of a deal now than in 2012 or back in 2010, when the eurozone was on the brink of collapse.

1. Stronger creditors: The structure of Greece's debt has changed dramatically. In 2010, 85% of Greek debt was held by private investors, leaving them with plenty to lose.

That ratio has flipped since then -- recent data from Open Europe show that 80% of Greek government debt is now held by governments and other institutions, such as the IMF and the ECB, which are better equipped to deal with a potential Greek default.

2. Risk is spread out: No single bank holds a significant chunk of the debt either, so no one creditor would take too much of a hit. Plus, foreign banks held just $46 billion of Greek debt at the end of 2014. That compares to $300 billion in 2010, according to data from Wells Fargo and the Bank for International Settlements.

And global banks aren't being punished despite the fact that the debt standoff is shaking confidence in the Greek financial system. Shares in the biggest Greek banks Piraeus (BPIRF) and Alpha Bank (ALBKF) have dropped by 51% and 32%, respectively, since the start of the year.

Related: Greece delays IMF payment as cash runs short

3. No fear of domino effect: Greece looks gloomy, but Portugal, Italy and Spain -- the other "troubled" eurozone countries -- are doing much better after working through their own painful bailout programs.

Bond yields tell the story. Investors are more willing to lend their money to the rest of the group, because they are less afraid these countries would follow Greece out of the eurozone.

Spain's 10-year bond yields now stand at 2.2%, compared to 7% in 2010. In fact, both Spain and Italy can currently borrow money cheaper than the U.S.

Related: Spain's economy charging ahead

4. ECB stimulus: The European Central Bank unveiled a big stimulus program in January, making investors very happy. The $1.3 trillion bond buying program is expected to help boost eurozone's growth. The cheap cash can help offset any potential fallout from Greece.

5. Economy growing: Europe, although battling the effects of a long recession, is in better shape now compared to the last time a Grexit was on the cards in 2012.

The eurozone economy grew by 0.4% in the first quarter, compared with the final quarter of 2014. The annual rate of growth picked up to 1%.

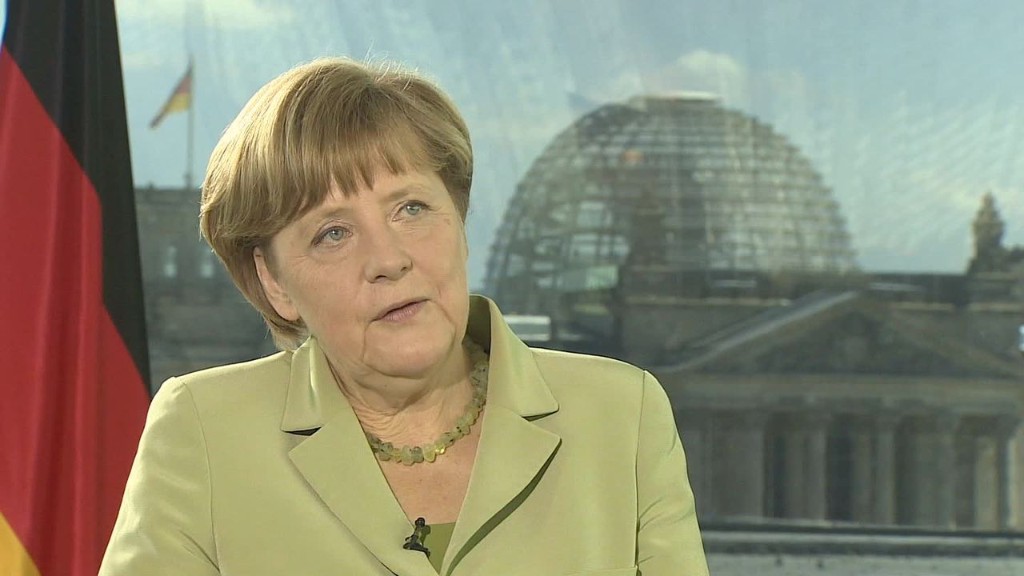

Related: Merkel says Greece needs to make 'harsh reforms'

6. New plan for member states: When the eurozone crisis first struck in 2010, the bloc's leaders didn't have any framework to turn to if a member state runs into troubles.

Since then, eurozone countries established the $800 billion bailout fund for emergency loans. They also agreed on rules on how countries can access this money.