For Jim Melo, being an American is a huge responsibility.

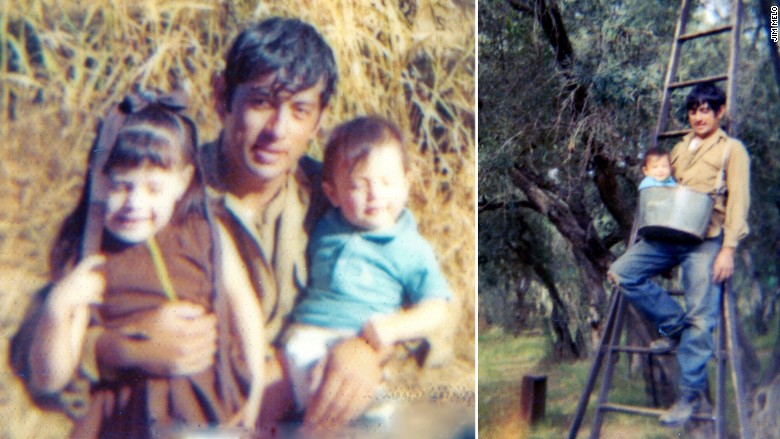

His parents and siblings came to the United States in the early 1970s without papers from Mexico. To survive, they picked fruit in Northern California, where Melo was eventually born.

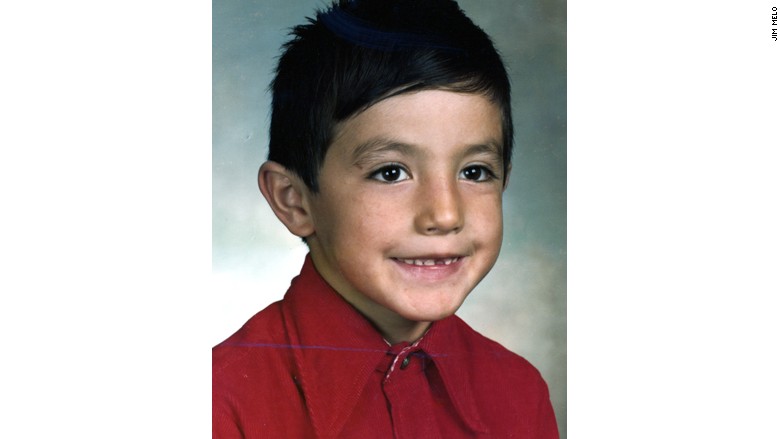

As the first person in his family to be born in the U.S., Melo put a lot of pressure on himself to succeed.

"I was the physical embodiment of my parents' American Dream," says Melo.

That drive spurred Melo to work hard in school, attain an Ivy League degree, graduate from law school and eventually open his own law firm in Durham, North Carolina.

"My parents told me 'you can do anything you want and be anything you want,'" said Melo, now 44. And from a very young age, Melo knew what he wanted.

"When people asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I never said 'fireman'... I never said anything but 'lawyer,'" he said.

He knew that a good education was the key to this dream and set his sites on getting into an Ivy League school -- either Harvard, Princeton or Yale.

"But no one was correcting my English at home, because my folks didn't speak English very well," he said. So he learned English from watching TV, particularly Sesame Street. And he read -- a lot. "I have a voracious appetite for books."

Melo's family moved to Ferguson, Missouri, when he was a toddler. And, in the late 1970's, they gained their U.S. citizenship through President Carter's amnesty program.

Even though Ferguson has become the epicenter of strained race relations, Melo says his early years there were idyllic. His father worked a union job building Corvettes at the nearby General Motors plant. His mom built military tanks at Sunbeam Corp.

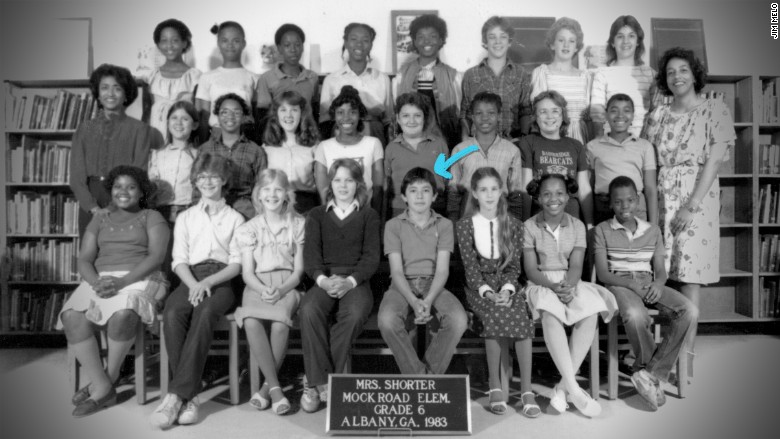

After elementary school, the family moved to Albany, Georgia because his father got a job at a Delco Remy auto parts plant.

Once they arrived in Georgia, "I quickly realized that the schools in the black neighborhoods were the bad schools and the ones in the white neighborhoods were the good schools," Melo said.

He also realized that if he wanted to get accepted into one of the Ivies, he would need to go to one of the good schools. So he asked his parents to buy a house in a good school district -- and they did.

Fortunately by then, Melo's parents were earning a good living. His dad had a good job in the auto industry and his mom was running several successful Mexican restaurants.

It was a good life, but as Melo entered his teen years, he grew rebellious. "I was drinking and smoking pot," he said. And after getting pulled over by police while driving home from a party one night, he knew he needed a change in environment.

Melo's brother was attending Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah and Melo asked his parents if he could live with him and attend high school there.

"The minute I walked [into my new high school in Utah] it was a world of difference," he said. "I took every AP class I could take, I got involved in student government and ran cross country."

He was so determined to go to Harvard, Yale or Princeton, that he only applied to those schools -- no safety school needed, he thought. He second-guessed this decision when he was wait listed at Harvard and Yale. Finally, he was accepted at Princeton.

After his first semester of college, however, Melo left for a two-year Mormon mission in Chile. While he was abroad, his father passed away and he began to question his religion.

"Religion was telling us that you couldn't do or be whatever you wanted to be," he said.

It was the opposite of what his parents had always told him. "The American dream won out," he said.

Melo returned to Princeton, graduated and then moved to San Francisco. He had taught himself HTML computer programming language and landed jobs working for various start ups as a programmer in the early days of the dot-com bubble.

And while he didn't become a millionaire (none of the companies he worked for went public), he says he made a very nice living. He stopped working just before the bubble burst and decided it was time to go to law school. "But first, I traveled the world and enjoyed my money," he said.

At 32, Melo embarked on getting his law degree from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

After he graduated in 2006, Melo practiced criminal law, but he eventually found himself taking on more and more immigration cases.

"It's not something I ever really wanted to do. Immigration law is mainly paperwork," he said.

But a growing number of his Latino clients were getting picked up by police and then disappearing or being held longer than the 48 hours that the law allowed.

By 2008, Melo was taking on immigration cases full time.

"Wake County was holding people for longer than the 48 hours, and a lot of my clients were being deported," he said. "So I sued the county under a writ of habeas and won."

Wake County now observes the 48 hour limit.

Melo has since returned to criminal law. One of his associates now handles the immigration cases.