Denisse Rojas was inspired to become a doctor by her undocumented immigrant family's struggle to obtain health care. But her path has taken her much further than that.

She not only went on to become the first undocumented student to attend the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, she has also made it possible for thousands of other undocumented students to attend medical schools all across the U.S.

"I want to be able to provide the care that I had limited access to growing up -- and to change policy," she said.

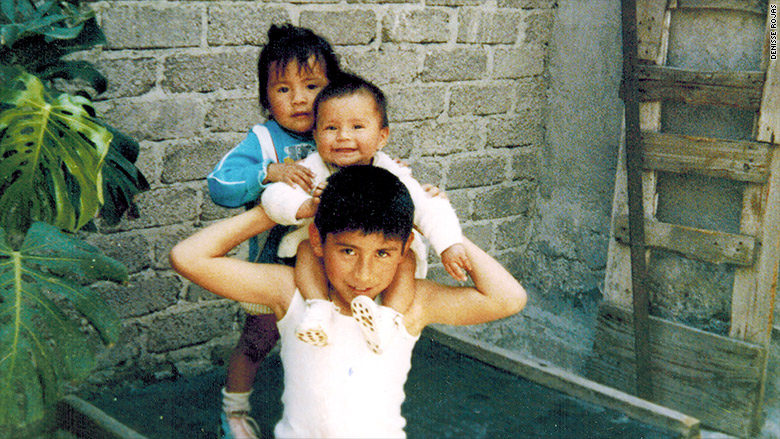

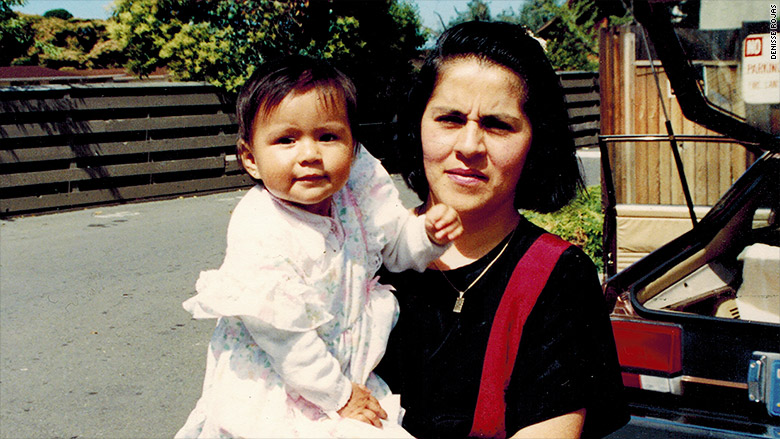

Rojas, 26, came to the U.S. from Mexico City when she was just 10 months old. As a child growing up in Fremont, California, she didn't quite grasp the impact of the family's undocumented status. She just knew money was tight.

But as she grew older, she started seeing things that made her increasingly fearful of the police -- and of being deported.

Related: I'm no 'anchor baby,' I'm Jim Melo -- an Ivy League-educated lawyer

"The scariest time was during the holidays," said Rojas. "If there was a DUI check, my parents could be jailed and deported for driving without a license."

She also saw her parents grieve when family members back in Mexico passed away and they were unable to attend the funeral.

Getting proper medical care was another issue. Undocumented immigrants often can't qualify for health insurance.

"My aunt waited a long time to go see the doctor and she was diagnosed with stage-3 gastric cancer and passed away in three months," Rojas said.

A lack of health insurance also forced her parents to leave the U.S. for Canada. They joined Rojas' brother, Edgar, who had moved to Ottawa after he was unable to obtain a visa to work as a computer programmer in the U.S.

Three months after arriving in Canada, Rojas' mother was able to get a surgery she needed to remove tumors from her uterus, Rojas said.

A lot has changed since Rojas' parents left.

Related: I'm no 'anchor baby,' I'm Yanely Gonzalez and I'm going to vote

In 2012, the Obama administration implemented Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, which gives undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children some protections from deportation and access to work permits for a period of two years.

"I was able to obtain health insurance, a driver's license, have safety from deportation and in essence become fully incorporated into society. In addition, DACA made possible my ability to enter medical school," Rojas said.

In addition to her medical degree, Rojas is also getting a master's in public policy. She wants to eventually practice medicine, perhaps as a general practitioner or OB/GYN.

Getting to this point has not been easy though. "I applied and was thrilled when I got the interview. But when the financial aid office made its presentation to all the students, none of it applied to me."

The school was familiar with the non-traditional financial aid needs on international students. However, they'd never had an undocumented student and didn't know how to handle the the ins and out.

"But they assured me that they wouldn't leave me hanging," Rojas said.

Related: I'm no 'anchor baby,' I'm LGBT gym owner Nathalie Huerta

Her financial aid package eventually included loans from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, her merit-based scholarship and some other scholarship awards.

During her last semester of undergrad at University of California, Berkeley, Rojas had met other undocumented students who dreamed of going to medical school and they began comparing notes about the hurdles they faced.

Many felt they were wasting hundreds of dollars on applications that would not even be considered. And if they only had a list of schools that accepted undocumented students they could save their much-needed money.

To help, the group created a web site offering this type of guidance and best practices for applying to schools and securing financial aid. For example, it recommends students apply to schools with strong international programs because these institutions are well versed at working with students with visa issues.

"We started getting responses from people saying thank you and we realized that this was something bigger," said Rojas.

The movement evolved and the group started speaking with admissions officers at schools that had been refusing to accept undocumented students.

Related: How this son of migrant farm workers became an astronaut

One by one, the schools began changing their policies.

Now, all of the University of California campuses and over 50 medical schools throughout the U.S. consider undocumented students.

Rojas and her advocacy group, Pre-Health Dreamers, also joined California State Senator Ricardo Lara, to successfully lobby for the passage of Senate Bill 1159, which allows undocumented Californians to get professional licenses.

It not only helps medical professionals, but gardeners, hair stylists, builders and anyone else that needs a license to operate legally or to become bonded and insured.

All of these have been major wins for Rojas. And in April, her accomplishments helped her to become one of 30 recipients to receive a Paul and Daisy Soros New American fellowship of up to $90,000 to help pay for her studies.

"I love this country!" she said. "This is home and I just hope to change the rhetoric about immigrants in this country and that others can see how much immigrants contribute."