Would you still fly if you couldn't see the sky?

The newest generation of airliners come in all different sizes, but they all have one thing in common: bigger windows.

But a new project from Airbus Group's Silicon Valley unit, A^3 (pronounced A cubed) is imagining a future without a direct view of the sky. The project, called Transpose, is rethinking what an airline cabin can be for passengers by making it quickly and inexpensively flexible.

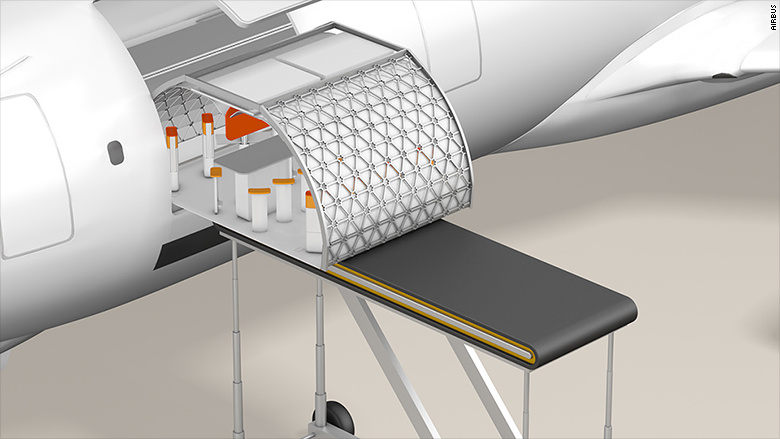

Like trains that add and remove sleeper cabins and cafe cars, Airbus is experimenting with the same concept for planes. Each module, piece-by-piece, would load on and off through a large cargo door onto a modified and nearly-windowless freighter.

The goal is to give airlines a blank canvas on which to design a new passenger experience and expand their revenue model beyond traditional tickets and fees.

Transpose imagines a flying Starbucks, sleeper bunks, a play zone for kids, gyms, spas or even a section for a movie studio promoting a new summer blockbuster.

Airbus offers a peek at its flying taxi

Through Transpose, Airbus is trying to solve an expensive problem for airlines. Over a half-decade of use -- or longer -- interiors get worn out and quickly outdated. A mid-life overhaul on a twin-aisle jetliner can cost tens of millions of dollars and take weeks.

"Airlines aren't allergic to change, but the cost makes it hard" to quickly try new things, said Jason Chua, Airbus's project executive.

Chua doesn't want to have to reinvent an all new airliner (that costs $15 billion or more). By using an adapted freighter based on Airbus's A330 long-range airliner, the goal is to change an interior in eight hours or less. It's already designed to haul large pallets and heavy containers.

But with train car-style customization comes a big, and potentially jarring change for passengers. The Airbus project wants to design "windowless technology" using OLED screens embedded in the walls of each module.

The Transpose team is digging deeper to find out if this is what airlines and passengers want. The project has rented a warehouse near San Jose to build in early 2017 a 150-foot long, 20-foot wide mockup to test out simulated flights. By the end of the decade, the team plans to demonstrate the concepts in flight.

But even as A^3 ponders a cabin without natural light, plane makers, including Airbus, have put windows at the center of the passenger experience.

Boeing's bigger windows on its new 787 Dreamliner were a major selling point. Their research suggested a connection to the sky was a hallmark of an improved flying experience. And seeing out bigger windows -- no matter where a passenger was sitting -- was central to that. The argument was so compelling that Airbus followed suit on its own all-new A350 XWB. The rivals have been sparring over who gives passengers a better view ever since.

Many long-range flights today, Chua contends, are flown with the window shades down.

But windows aren't only for passenger comfort -- they're also for safety. Many airlines request passengers keep their window shades open for takeoff and landing to see outside during an evacuation to avoid any hazards. The same goes for emergency crews looking in from the outside.

Transpose will still have some windows, at least six on each side of the plane to make sure cabin crews can see outside in an emergency. "You can have a great experience, but if it's not safe, people shouldn't be flying. That's definitely our first priority," said Chua.

Airbus's design isn't the only future vision without a view. Aerospace engineers at Boeing have long been studying a blended wing body design that is leaps more efficient than traditional planes. But such designs separate the passenger cabin into windowless rooms.

Hans Weber, an aerospace consultant at TECOP International, said the increasing proclivity toward staring at screens, whether our phones or virtual reality, might make losing the view easier to take. Someday we'll say of windows, "that's an anachronism," said Weber. "That's how we used to do things."