Sal Moceri gets visibly agitated at the very mention of the word "NAFTA." He thinks the trade deal killed the American Dream.

"NAFTA was one of the worst contracts ever negotiated for the American worker," the 61-year-old Ford worker told CNNMoney.

Moceri has one of the coveted jobs that President Trump wants more of in America. He earns about $30 an hour fixing tools at a Ford (F) plant in Detroit. The job has allowed him to send four kids to college.

He calls himself a "lifelong Democrat." That is, until 2016, when he voted for Donald Trump, largely because of Trump's vow to redo NAFTA.

Michigan has lost nearly 300,000 manufacturing jobs since 2000. Moceri kept his job, but he says he has a lot of friends who didn't.

Many economists say there's no way those jobs will come back. The problem, they argue, is that machines took over. One study by Ball State University says 87% of American manufacturing jobs have been lost to robots. Only 13% have disappeared because of trade.

But workers in Michigan think the experts have it wrong. They don't blame robots at all. In fact, they love the machines.

"Automation is great. I want it to excel. I want more computers. I want more robots," says Moceri.

Frank Pitcher, a fellow Ford worker and UAW union member, agrees. He strongly believes robots have saved workers' backs and caused Ford employees to become a lot more skilled.

Robots have "replaced a lot of jobs that actually injured people," says Pitcher, who is about to turn 50 and glad his body isn't busted up. "I don't fear the technology or the automation. I welcome it."

CNNMoney spent a week in the Detroit metro region talking to current and former manufacturing workers. Almost all said the same thing: It's not the robots that took U.S. jobs, it's NAFTA.

Related: Trump gives America's 'poorest white town' hope

'I've had to let most of my workers go'

A giant American flag hangs on the wall of Matt Seely's small manufacturing shop in Detroit. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, his company, Quality Bending and Threading, was buzzing. He employed 17 workers. The phone rang all the time with orders from the big auto companies and defense contractors for specialty steel parts.

Today he employs just five people. He blames NAFTA for the decline.

"There was a point in time before NAFTA came in where there was a machine shop like this literally on every corner in the metro Detroit area," Seely says. Now he thinks people don't want to pay for American-made when they can get it cheaper from Mexico.

NAFTA was the trade deal President Bill Clinton signed with Mexico and Canada that went into effect in January 1994. It allows many goods to be imported into the U.S. from those countries without being taxed.

"We're not trading equally, and that's the real issue," says Seely. He believes it's not fair the U.S. ran a $63 billion trade deficit with Mexico last year, meaning the U.S. bought more from Mexico than it sold to Mexico.

Seely says he was never much of a political guy, until Trump camp along. He and his wife volunteered for Trump and ended up running a campaign office. Trump's son Eric toured Seely's factory.

Trump has clearly tapped into this anti-NAFTA fervor. He campaigned hard in Michigan, holding four rallies there in the final week before the election. He vowed that "Detroit -- the Motor City -- will come roaring back." He ended up winning Michigan by 10,704 votes.

Related: Mexico ready to retaliate by hurting American corn farmers

Trump calls NAFTA a 'catastrophe'

Since taking office, Trump has called NAFTA a "catastrophe" and promised to start renegotiating it this spring. It's exactly what Ken Sultes, another Ford worker and union member, wants to hear.

It's been "a downward spiral as far as jobs leaving this country," laments Sultes, who loves cars and wore a BMW ball cap to his interview. He also thinks the experts have it wrong about what's been hurting his industry.

"It's not like a robot comes to a line and 500 people lose their job," he explains. Sultes says only a few jobs are replaced by machines at a time. Typically, the displaced workers stay in the factory and move to another job.

In contrast, manufacturing workers are well aware of when there's a big factory closing. When that happens, hundreds of jobs go to another state -- or overseas.

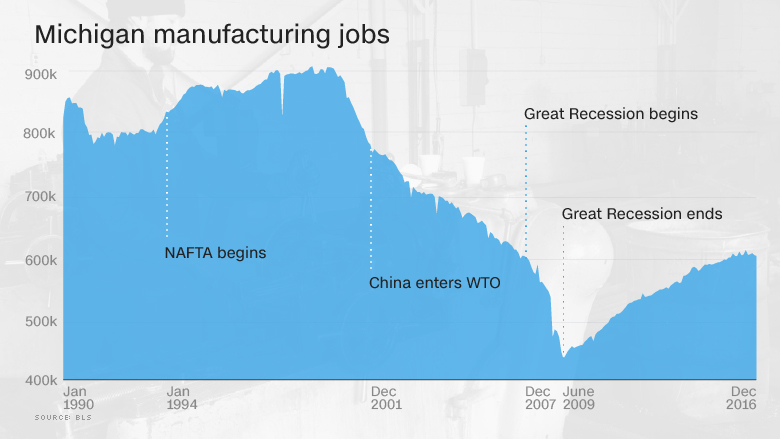

While Trump and many workers blame NAFTA for the Rust Belt's woes, the data shows a far more murky story. Michigan actually gained manufacturing jobs after NAFTA was signed in 1994. The real downturn didn't begin until 2000, around the time China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

The Great Recession caused more losses, although Michigan has actually rebounded from the worst of the crisis. Over 150,000 manufacturing jobs have come back since the low of 2009. It's helped that U.S. car sales have been at record levels lately.

Related: I raised 3 kids on minimum wage. Here's what Trump should know

Michigan: Some jobs are back, but at what pay?

While there's a lot of worry in Michigan, the state's unemployment rate just hit 5%, the lowest level since 2001. That implies there are jobs in Michigan again.

But workers likes Sultes and Pitcher argue the jobs around now aren't middle-class jobs, especially for workers just getting started. Even at the auto plants, the big companies like Ford have created a "two-tier system" where they pay some employees about $30 an hour and others a far lower wage of about $20.

Many workers blame NAFTA -- especially cheap Mexican labor -- for pulling down U.S. wages.

"We never had a two-tiered employment where I worked before the NAFTA program," says Moceri, shaking his head. The company basically said, "If you don't accept this lower wage, this job will be gone."

-- CNNMoney's Logan Whiteside and Richa Naik contributed to this story.