If British voters were hoping for televised debates to help them decide in the election that was just announced, they'll be disappointed.

There won't be any -- at least not featuring the prime minister.

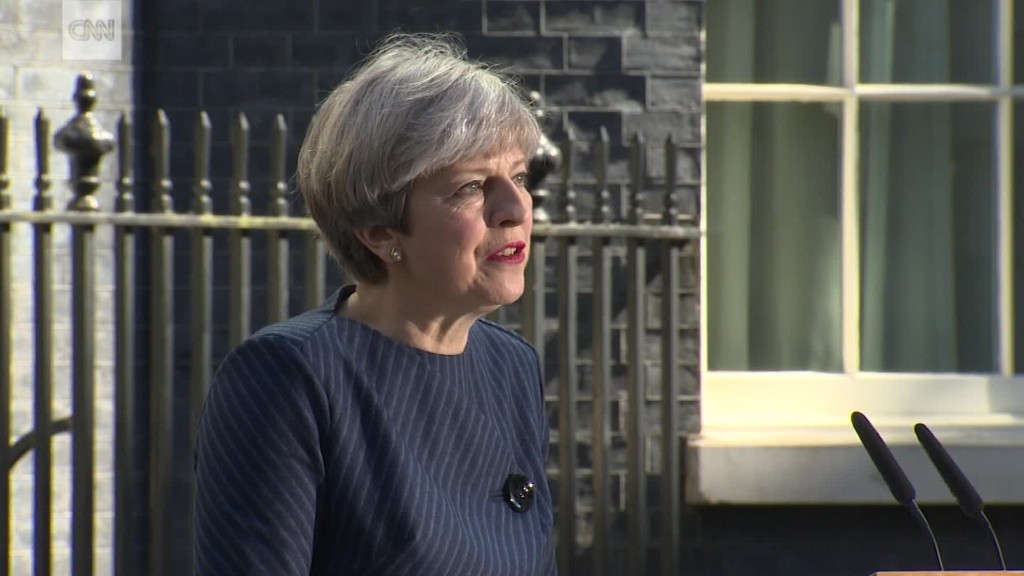

Theresa May, who called for an early general election on June 8, has indicated she will refuse to debate her challengers. She says she already debates them once a week, during the session known as Prime Minister's Questions.

The opposition says she's running scared.

"If she's so proud of her record, why wouldn't she debate it?" Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn asked in Parliament on Wednesday.

Tim Farron, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, asked: "What is she scared of?"

May stepped in as prime minister without winning a general election or facing a debate. Her predecessor, David Cameron, resigned after Britain voted last year to leave the European Union. May is calling for the early election in June because she wants a bigger mandate in Brexit talks.

In the United States, generations of voters have grown used to debates and consider them part of the job application. France held hours-long debates ahead of its upcoming presidential election. Germany's Angela Merkel will almost certainly face off with her challengers later this year.

But Britain doesn't have much of a tradition of televised debates.

Former Prime Minister John Major famously said that only politicians who expect to lose agree to debate. Margaret Thatcher, according to her authorized biography, also rejected the idea, saying that "policies should decide elections, not personalities."

Brexit: U.K. election makes a painful breakup more likely

That changed in the 2010 election, when the leaders of the three biggest parties faced off on TV. Experts credit those debates with giving a platform to Liberal Democrats leader Nick Clegg, who led his party to major gains in Parliament.

The format suited Cameron, then the leader of the opposition. He pressed for the TV debates, anticipating he would do better than Prime Minister Gordon Brown. Cameron won the election.

For the 2015 election, seven leaders participated. Cameron wanted a wider, "more diluted" debate, said John Bartle, a political communication expert and education director at the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

Now it looks like the experiment is over.

"The prime minister is not a personality that enjoys this kind of thing," Bartle said. "And she's got nothing to gain from it. She is expected to win the elections, and she doesn't want to risk a disappointing debate."

Related: They want to kill the euro

Opposition voices have called for the debates to go forward anyway, with an empty chair for May. Bartle thinks that's unlikely.

"The TV companies would be very cautious about embarrassing the person who is likely to be a strong prime minister," Bartle said.

And they could get in trouble with regulators: Under British election law, major broadcasters must dedicate a "due amount" of coverage to major parties. Leaving out the frontrunner could be a problem, even if it was her decision.