It all started with wine from Portugal. And it's served as the foundation to free trade.

A key trade theory turns 200 years old Wednesday. The marquee birthday comes at a time when President Trump is trying to redefine U.S. trade with other countries.

Published on April 19, 1817, British economist David Ricardo used a now famous example of wine from Portugal versus cloth from England to talk about trade in a paper entitled: "On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation."

His theory was that it took fewer workers in Portugal, a country with a long history of wine making, to make wine than it does to make cloth in that country. And it took fewer workers to make cloth in England, a textile powerhouse at the time, than to produce wine there.

Thus, Portugal should export its wine to England, while England should export cloth to Portugal. Workers weren't the only factor. Other considerations were equipment, skills and the value of currencies.

Related: IMF warns world leaders not to erect trade barriers

The idea in a nut shell: Focus on your biggest advantages and sell them to other countries.

Ricardo called it "comparative advantage."

The main concept: You focus on the products you're most efficient at making and ship them to other countries. Then other countries focus on what they're most productive at making and export those products to you.

"The idea of comparative advantage has been an essential part of every economists' intellectual toolkit," Dartmouth professor and former Reagan trade adviser Doug Irwin wrote in a blog post Wednesday.

The same concept is true today in the U.S. economy.

Consider this example: the U.S. is a leader in manufacturing airplanes. Boeing (BA) exports its jets to countries and airlines around the world.

Related: Fed: Pulling out of NAFTA would hurt U.S. companies

For instance, Boeing sells planes to Avianca, the Colombian airline. Colombia doesn't have much of an airplane manufacturing industry. But Colombia does have a robust coffee industry. And Americans love coffee.

So, Ricardo's theory plays out on a very basic level in this interaction -- the U.S. imports loads of coffee from Colombia while Colombia buys U.S.-made planes.

More broadly, Ricardo's idea plays out across the global economy. The strength of the U.S. is largely in services like education and it has a trade surplus in services with the world. Mexico produces goods like car parts and it has a goods surplus with the U.S. and many other nations.

The problem in Trump's view is that Mexico, for instance, is selling more goods to the U.S. than the U.S. is selling to Mexico. That creates a trade deficit. Trump wants to eliminate that, but hasn't shared any details on how he would do it.

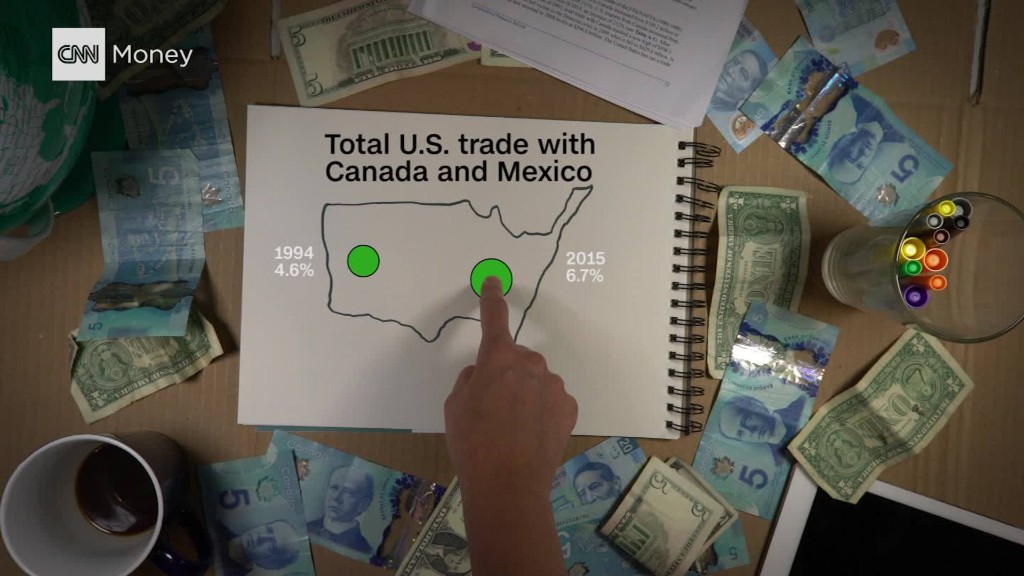

Ricardo's timeless theory could be tested again when the Trump administration renegotiates NAFTA, the free trade deal with Mexico and Canada, this year.

The U.S. though, with its Napa and Sonoma Valleys, does have at least one notable, comparative advantage over Mexico and Canada: Wine.