President Trump on Tuesday threatened to make trouble in negotiations for next year's budget.

"Our country needs a good 'shutdown' in September to fix mess!" he tweeted.

A president calling for a shutdown of a government that he and his party now run is problematic for many reasons.

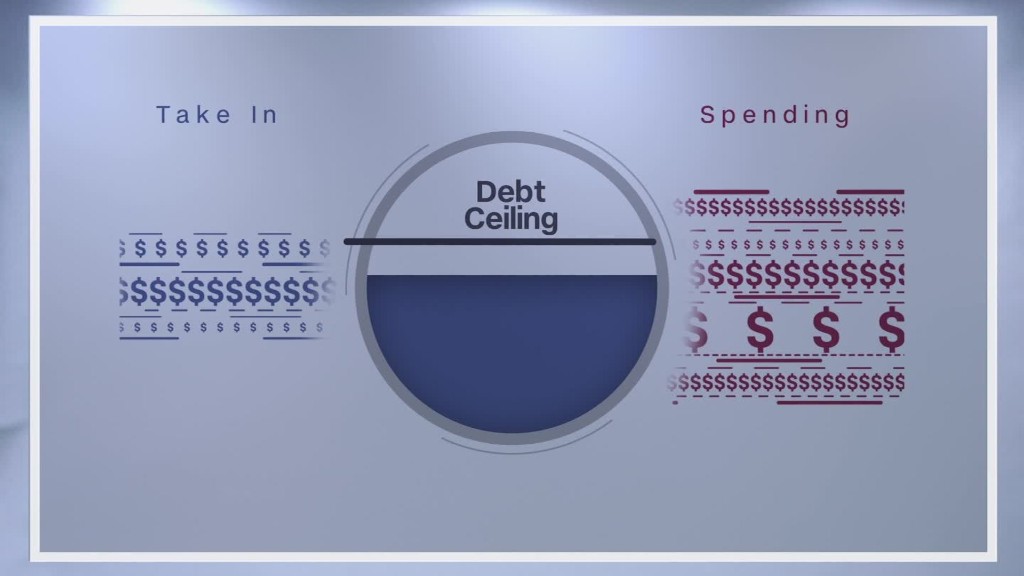

But it is especially so because it could invite gridlock when negotiating another crucial issue: the U.S. debt ceiling. That's the legal borrowing limit that must be raised or suspended this fall if the United States is to avoid a default on its debt.

To be clear, a government shutdown and a debt default are two very different things with different consequences. A default is far worse, though, because U.S. debt is considered the safest investment in the world. Missing any payments due -- first to bondholders, then to everyone else (e.g., federal contractors, Social Security beneficiaries, soldiers, etc.) -- would risk a market and economic crisis.

Treasury working on borrowed time

The debt ceiling is currently set at $19.8 trillion. Debt levels are near that cap and Treasury has begun using special accounting measures to keep outstanding debt just below the limit. But those measures are only expected to last until sometime this fall.

At that point, if nothing is done, Treasury won't have enough cash and revenue on hand to pay all the country's bills in full and on time.

Related: Treasury Secretary Mnuchin calls out debt limit as a "ridiculous concept"

Congress must decide whether it wants to raise the debt ceiling by a specified amount or to suspend it for a period of time, during which Treasury would be allowed to borrow what's needed to pay the country's already-incurred obligations.

But it can be an ugly fight, when lawmakers seeking leverage to get what they want make hard-line demands in exchange for their votes.

Now add to that potential cauldron Trump's volatile style coupled with his early warning that he's willing to risk a shutdown over funding. That could breed even more bad blood with Democrats and even some Republicans, creating a recipe for high-stakes brinksmanship.

Lawmakers need to agree on a 2018 budget

Lawmakers must now pivot and start the budget process for fiscal year 2018, which starts October 1. Ideally, they will adopt a budget resolution that sets out their topline numbers for 2018 (e.g., how much to spend in broad spending categories and how much revenue to raise).

This year, Republicans also want to include so-called reconciliation instructions that would let them pass tax legislation with a simple majority in the Senate instead of the typical 60 votes required.

That way, if they can't garner Democrats' support, the 52 Republicans in the Senate can pass the bill on their own.

The budget resolution also could include a decision to raise or suspend the debt ceiling. That would be the easiest path.

But there's a fair chance that lawmakers won't be able to agree to a budget resolution this year.

"Failure to do so means everything in the Senate relating to debt and, separately, the [budget] process, will need 60 votes for passage," said Steve Bell, a former Senate Budget Committee senior staffer who is now senior adviser at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

That could upend Trump's and the GOP's legislative agenda.

Related: Congressional negotiators reach deal for funding through September

But failure is a possibility because the Republicans are not speaking with one voice.

The fiscally conservative Freedom Caucus may demand that the budget resolution require a balanced budget at the end of 10 years, Bell said.

That won't square with Trump's calls to increase spending in a variety of areas, including defense and infrastructure, while refusing to consider changes to the biggest spending programs -- Medicare and Social Security.

Plus there's no agreement that Republicans' desired tax cuts would have to be offset so that they don't increase deficits. Republican leaders have been pushing for that, but not everyone in the rank-and-file agrees. Nor apparently does Trump, whose one-page tax plan outline could add $5.5 trillion to deficits in the first decade.