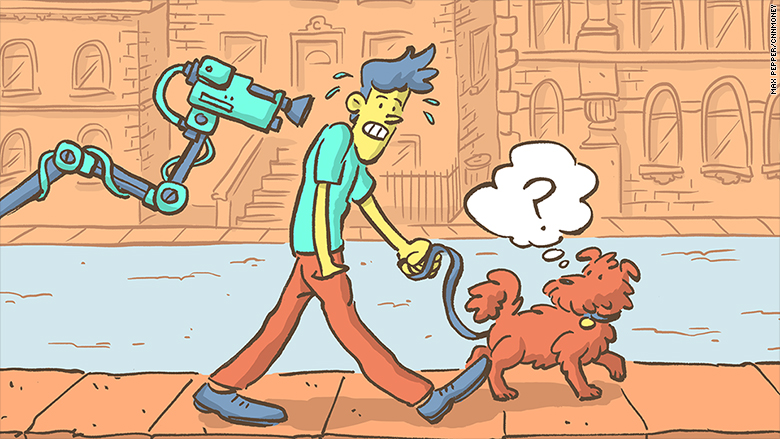

If you're walking a dog in Moscow, make sure you clean up after it.

Moscow's government is upgrading its network of 146,000 cameras to better monitor city streets and make sure residents, businesses and visitors are staying in line.

Moscow's government has steadily built out the massive network of cameras over the past five years. They're posted along streets, giving the government a 24-7 view of street activity. They are mounted on everything from street lights to buildings and construction sites.

As governments around the world plant more eyes on the streets, people may have no choice but to be upstanding citizens. Crime might drop. But questions about privacy and civil liberties will also be raised. How much surveillance will people put up with? And what happens if camera data falls into the wrong hands?

In Moscow, the technology is a double-edged sword, according to Mark Galeotti, a senior researcher at the Institute of International Relations in Prague.

"It's this funny combination of big brother in both the negative and the positive sense of the word," Galeotti told CNN Tech. "It's an authoritarian regime that wants to have all the capabilities for a security state. At the same time, [the Moscow government] is genuinely committed to providing public services, and is committed to a wired up city and pushing the various ways that new technology can actually make it better."

Galeotti said he's been struck on his visits to Moscow by the number of city services that can be accessed on a smartphone.

Currently, the cameras are used to check if the trash is picked up, crack down on speeding and red-light running, make sure on-street advertising is legal and track snow removal. Roughly 75,000 violations are caught per day, according to Andrey Belozerov, senior adviser to the Moscow city government's chief information officer. Violators generally receive a fine.

But the local government isn't content with its success. It sees far more potential in the cameras, which have cost $250 million, according to Belozerov. It's working to make its system more intelligent so that video footage can be analyzed more deeply. Computer programs could analyze footage, automatically doling out tickets.

"For the future, we would like to have more algorithms, starting from whether a seat belt is fastened or not, or is a person talking [on] a mobile phone," Belozerov told CNN Tech.

Related: This company offers U.S. cops free body cameras

Moscow's experimentation is possible due to recent breakthroughs in computer vision. Engineers in the field are highly sought after.

"If you see a computer vision person walking down the street, you grab them by the neck," said Andrew Moore, dean of Carnegie Mellon University's school of computer science. "So many products depend on having great computer vision engineers."

The dream of computer vision researchers is to one day empower machines to see as well as humans. It's unclear when this may happen, but the implications of computers' new abilities will be vast.

And that's why dog walkers in Moscow should get used to cleaning up after their animals. In a matter of years, governments will be able to monitor and enforce good behavior like never before. Belozerov can foresee using cameras to automatically identify when a person doesn't clean up after their pet. Leave your dog's waste behind, and you risk getting a ticket in the mail.

In theory, a government could do this already. But it would require humans manually monitoring thousands of video feeds. That would be too expensive. But by automating the task with computer vision algorithms, it would become an affordable option for identifying bad behavior.

Related: New Nest camera zooms in and recognizes faces

Earlier this year, Belozerov did a pilot test of facial recognition technology outside Moscow subway stops. Some cameras were able to recognize faces with 95% accuracy. Belozerov envisions making the technology available to the police department to aid in looking for criminals.

For now, the technology is still a work in progress. Some cameras in the pilot proved ineffective, due to the lighting or the vantage point.

As the cameras have proliferated, the city has had to address privacy concerns.

"The technology is relatively neutral. The real question is what is the political, economic and social context in which that technology is deployed," said John Verdi, VP of policy at the Future of Policy Forum.

There are more than 15,000 people in Moscow's local government who can access the video footage, some with restricted access, according to Belozerov. For example, school officials can only access video from the cameras outside schools. The police department gets first dibs if it wants to point a camera in a given direction, or zoom in on something. All of Russia's federal agencies can receive camera footage upon written request.

Video recordings from the cameras are stored for five days.

"If we had more money," Belozerov said. "We'd probably buy more storage."