The U.S. city bus has fallen on hard times. Commutes are becoming painfully slow. Ridership is down.

Most buses must sit at red lights and jockey for space with cars. After buses pull over to pick up passengers, they have to wait for another vehicle to allow them back into the flow of traffic.

"The vast majority of cities are experiencing what can only be described as a crisis in ridership," said Yonah Freemark, the founder of The Transport Politic. "It's no surprise people are choosing to take other modes of transportation. It's simply too slow to take the bus."

In the age of Uber, it might seem prudent for cities to stop investing in buses. But some are doubling down on buses with innovations that bolster a service these cities see as vital.

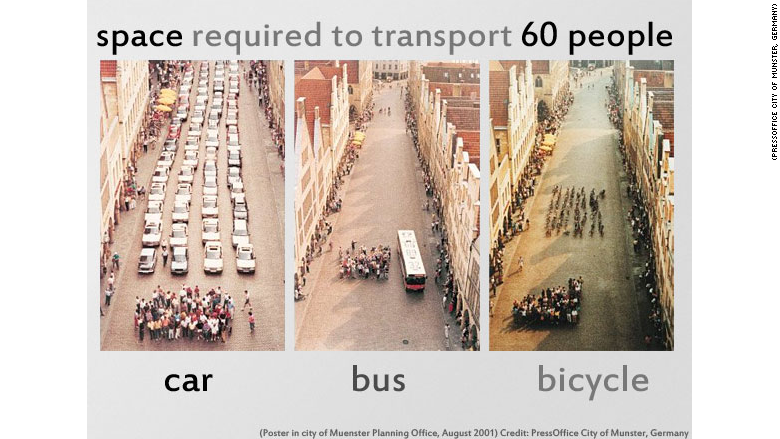

As cities almost universally struggle to address traffic congestion, experts say buses are a solution. Bus ridership is an extremely effective use of precious street space.

"If you stop being innovative with your transit system than you're going to continue to lose ridership," said Michael Riordan, the chief operations officer for the City of Albuquerque. "We know when you add a premium service ridership responds."

For example, Albuquerque is currently installing bus-only lanes on Central Avenue, the backbone of the city, a part of historic Route 66. These buses won't be slowed by regular traffic, making them fast and appealing for riders. Traffic lights will cater to the buses, remaining green longer when a bus approaches.

Seattle is a rarity among big cities -- its bus ridership is actually on the rise.

The city relies on every tool in the bus innovation playbook, from dedicated lanes to giving buses a head start at traffic lights. Green lights are held longer so buses keep moving. The city has used "bulb outs," where the sidewalk extends farther into the street. That way buses don't have to pull out of the flow of traffic to get passengers, which slows them down.

Related: Uber and Lyft are creating a traffic problem for big cities

"In order for Seattle to continue to thrive, to be a livable place, where people want to work and live, transit has to work," said Andrew Glass Hastings, the transit mobility director for Seattle's Department of Transportation.

The city has grown dramatically in recent years, as Amazon and other companies have blossomed. It invested in buses because that was the fastest way to adapt mass transit to an influx of new residents.

Los Angeles announced this week it will test a "microtransit" service next year.

Vehicles smaller than buses but larger than cars will transport people. Riders will generally book a ride with an app and be asked to walk to a nearby street corner for pick-up. Routes will adjust on the fly, depending on where people are going.

Joshua Schank, chief innovation officer for the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority, sees it as an attractive option for sprawling areas where it's a challenge to run buses frequently enough to attract passengers.

"This is the kind of bold experimentation that's needed to solve our transportation problems," Schank said. "We can't sit idly by and watch new technologies come and go, without seeing how they fit in to the transportation landscape."

Yet Freemark cautions about what may happen if more cities don't experiment.

He warns that today's bus crisis could trigger a vicious cycle: fewer rides means less money to invest in buses. And with less investments in buses, service will decline. With bad service, even more riders will shift to less efficient modes of transportation, worsening congestion and pollution.