General Electric has been a piston of the American economic engine for 125 years. It pioneered the light bulb and the jet engine. It survived the Great Depression, the dot-com crash and the 2008 financial meltdown.

But now GE faces a different kind of challenge -- a nightmare cash crunch that could take years to recover from. GE (GE) has been left in turmoil by years of questionable deal-making, needless complexity and murky accounting.

These problems were self-inflicted. And they are startling because they happened not just at an icon of American business but under two legendary CEOs, Jack Welch and Jeff Immelt.

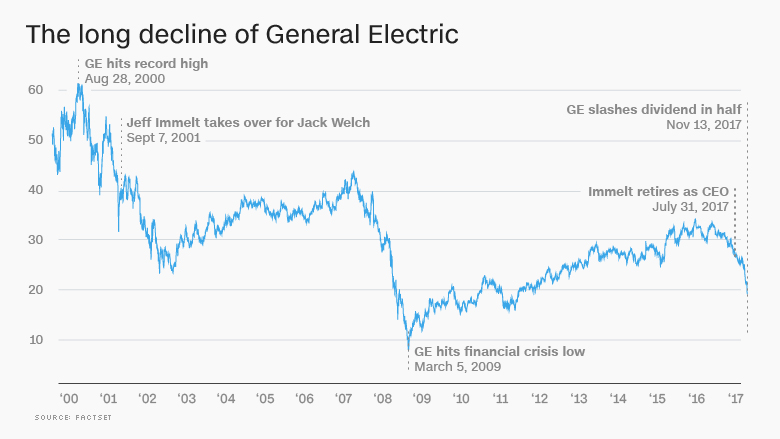

For GE's 300,000 employees and millions of shareholders, the consequences have been painful. More than $100 billion in market value has vanished from GE since November 2016, more than the combined values of Ford (F), Delta (DAL) and UnitedContinental (UAL). GE, still a staple in investment portfolios, has plummeted 42% this year.

The stock crashed to a six-year low last week after the company admitted it can no longer afford the dividend that once symbolized its stability. It's only the second time since the Great Depression that GE has cut the dividend.

John Flannery, the CEO brought in to clean up the mess, acknowledged that fixing GE will take time and require selling off another chunk of its shrinking empire.

This mainstay of corporate America is experiencing a low point even as the rest of the economy surges.

"When many people think of GE, they think of America," said John Inch, a Deutsche Bank analyst who covers GE. "It's hard for them to understand how this thing fell apart so quickly."

Related: GE is broken. Fixing it will be long and difficult

GE's shopping spree gone bad

Welch, the CEO from 1981 to 2001, built GE into a super-conglomerate that owned a major bank and NBC. But that business model has since been cast aside as overly complex, and in retrospect, it's clear that Welch's shopping spree masked problems.

Those problems blew up when he left. The most obvious example is GE Capital, the finance company that dealt GE a near-fatal blow during the 2008 crisis.

"Immelt inherited a company from Jack Welch that had brushed a lot of issues under the rug," Inch said.

Martin Sankey, a senior research analyst at Neuberger Berman who has been following GE closely since 1981, said Welch made his share of mistakes with deals and operations, "some of which showed up on his watch and others showed up later."

Not long ago, the criticism of Welch would have been unthinkable. He was a larger-than-life force whom Fortune named "manager of the century" in 1999. That aura has since been punctured.

Welch, who declined to comment for this story, still appears frequently on CNBC. He recently launched an online MBA program at Strayer University, named after himself.

Related: GE is breaking up with the light bulb

'Train wreck'

One of the chief responsibilities of the CEO is deciding where to deploy cash. After Immelt took over from Welch, GE often picked the wrong places at the wrong times.

Those poor decisions about mergers and acquisitions have contributed to the cash crunch: This giant company no longer generates enough money to pay for investments in the business and dividends for shareholders. The crunch has been years in the making, but only recently has Wall Street come to grips with how bad it is.

Consider GE's $9.5 billion acquisition of Alstom's power business, which makes coal-fueled turbines used by power plants. The 2015 transaction was GE's biggest-ever industrial purchase.

For GE, the deal represented a doubling down on fossil fuels, even as renewable sources of energy, like solar, were gaining popularity. Not surprisingly, GE admitted this week that Alstom has been a major disappointment, and that its power business is in shambles.

"If we could go back in the time machine today, we would pay a substantially lower price than we did," Flannery said on CNBC.

Inch called the Alstom deal a "disaster" that supports GE's reputation for "buying high and selling low."

Elsewhere, he said GE overpaid for many of its oil-and-gas properties, forcing it to merge those businesses last year with Baker Hughes (BHGE), a major provider of services and equipment for oil drilling. GE said this week it's already exploring ways to exit its majority stake in Baker Hughes.

GE has had an "abysmal M&A history," Scott Davis, CEO and lead analyst at Melius Research, wrote in a recent report.

Much of it occurred under Immelt, who himself once had a reputation as a world-class CEO. He was named one of the "world's best CEOs" by Barron's three times and sat on CEO councils under both President Trump and former President Barack Obama.

Yet GE was the worst-performing stock in the Dow during Immelt's 16-year reign. It was an original member of the venerable stock average. Now there's talk of kicking GE out of the Dow altogether.

Davis described Immelt's tenure was a "train wreck" and said his exit this year "came about 10 years too late."

Related: Will GE get kicked out of the Dow?

Immelt is gone now, and GE is shedding businesses -- but at a time when many of those businesses are at a low point. For instance, the company has put its century-old railroad business up for sale. But Flannery has warned that rail faces a "protracted slowdown" in North America, suggesting that buyers will not exactly be lining up.

Likewise, GE is looking to unload its business that makes light bulbs -- the product that, perhaps more than any other, symbolizes the company's history of innovation. Light bulb sales soared between 2007 and 2014, thanks to the LED lighting that GE helped to invent. The problem is that LED bulbs last for decades, so sales have tumbled.

Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at the Stern School of Business, blamed Immelt for not moving more quickly and aggressively to shrink a maturing GE.

"Accept the fact you're aging. Don't fight it with acquisitions," said Damodaran. "That's like a 75-year-old doing a face lift. You can't look good for long because gravity will work its magic sooner or later."

Immelt declined to comment.

'Too proud' to let go of GE Capital

Consider GE Capital, which was built into a behemoth by Welch and Immelt through a series of acquisitions. It was essentially a too-big-to-fail bank, inside a company that makes power plants and MRI machines.

GE Capital became a huge liability during the financial crisis. It got so bad that GE couldn't borrow money when the overnight lending market vanished, forcing it to get an emergency investment from Warren Buffett and other investors.

Pankaj Patel, who worked at GE during the 1990s, defended GE management by arguing the company was a victim of a once-in-a-generation meltdown.

"They got caught in the middle of the financial crisis," said Patel.

Others argue GE should have sold GE Capital long before it got so big that it endangered the rest of the company.

"They were too proud. They couldn't let it go. By the time they spun off GE Capital, it was already damaged and nobody would give them a fair price," Damodaran said.

Related: GE cuts dividend for 2nd time since Great Depression

'Murky' accounting

GE has long been criticized for using cloudy accounting and confusing reporting metrics that made it difficult for investors to determine the company's true health.

The SEC charged GE with accounting fraud in 2009, alleging the company used "overly aggressive accounting" to make false and misleading statements to investors. GE agreed to pay $50 million to settle the charges, though the company neither admitted nor denied wrongdoing.

GE's accounting remains controversial. The Wall Street Journal published a recent series highlighting how the company's "murky" accounting makes it hard to understand its cash flow.

Take GE's "industrial CFOA," which is supposed to gauge free cash flow. But a footnote explains this measure excludes deal taxes as well as pension plan funding, a huge cost at GE.

"It's gone on for many years," said Deutsche Bank's Inch. "The important numbers are buried. They don't want people to understand."

Acknowledging that these issues have hurt GE, Flannery promised last week to simplify reporting and increase transparency. However, GE stopped short of abandoning customized metrics altogether.

Flannery has downplayed accounting concerns, telling CNBC, "There is no accounting issue. ... No one's been had."

GE declined further comment.

Accounting scrutiny is a headache GE does not need. Flannery already faces what he calls a "heavy lift" turning around this great company. He expressed optimism about that challenge, citing GE's long history of remaking itself.

For this next chapter in the GE story, the company is planning to shrink itself by selling its transportation, light bulb and other businesses.

The goal is to make the GE of the future more nimble, easier to operate and squarely focused on its core strengths: health care, power and aviation. Flannery has also vowed to improve GE's culture by making it more open and transparent. And to do a better job of allocating GE's limited resources.

The dream is to make GE a modern industrial leader that is once again on a sustainable financial path.

"This is the opportunity, really of a lifetime, to reinvent an iconic company," Flannery said.