David Michael Jones can't resist describing the house he bought a year ago in a suburb of Killeen, Texas — it's 2,800 square feet, set up on a hill, with a formal dining room and an enormous master bedroom that includes a bathroom big enough to do cartwheels in.

"To me, I'm on top of the world," says Jones, 68, a reverend and father of nine. "It's my world, but I'm on top of it."

Jones credits his ability to buy such an ideal abode, in large part, to his long career with the military. He retired with a full pension and disability benefits that total about $70,000 a year, and obtained special home loan financing through the Veterans Administration in a place where houses are plentiful and affordable. And as a fully disabled veteran in Texas — resulting from his post-traumatic stress disorder, diabetes and hypertension — he doesn't have to pay property taxes either.

Jones' path to real estate bliss is far from the norm for African Americans.

Fifty years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act, which banned lending discrimination on the basis of race, the black homeownership rate in the US is back down to where it was in the 1960s. That's mostly because of a precipitous decline that began in 2000, as African Americans were disproportionately hard-hit by predatory lending and the foreclosure crisis that followed.

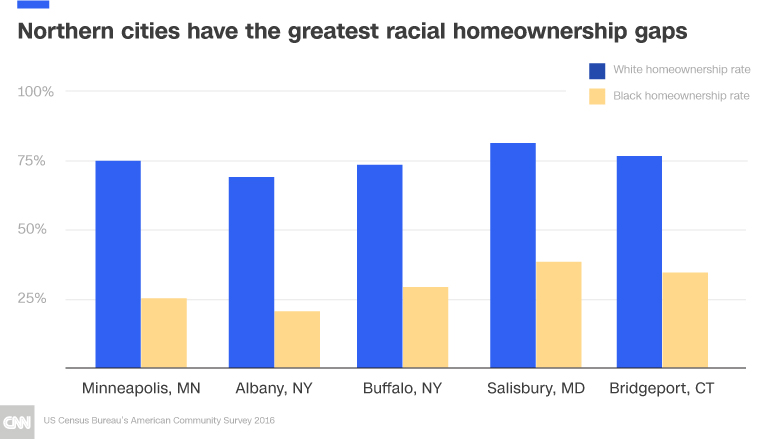

In 2015, only 41.2% of black households owned their homes, compared to 71.2% of white households. That disparity explains much of America's staggering wealth inequality, with the median white family owning ten times the assets of the median black family.

But Killeen, a city of about 140,0000 people located an hour's drive north of Austin, is different.

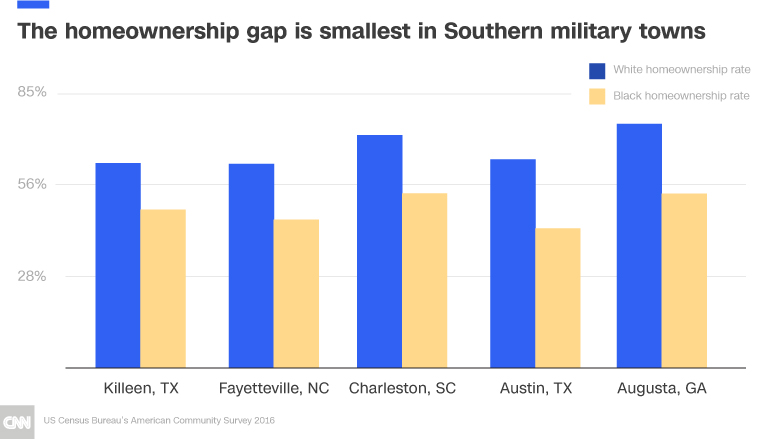

According to an analysis by the Urban Institute, a non-partisan think tank, Killeen has the lowest racial homeownership gap in the country. In this metropolitan area, the white homeownership rate is only 14.5 percentage points above the rate for the city's black households, which stands at 48.5%.

Related: How Colorado became one of the least affordable places to live

The reason: Fort Hood, one of the largest military installations in the United States, serves as a powerful on-ramp for opportunity for historically disadvantaged populations. (The city with the next smallest racial homeownership gap is in Fayetteville, North Carolina, which is home to the mammoth Fort Bragg.)

Although Fort Hood says it does not track the racial composition of its active duty population of about 37,500 people and 46,500 family members, African Americans are overrepresented in the armed forces generally, and 40% of Killeen's overall population is black.

Most soldiers live outside Fort Hood's walls, in private housing. On top of their base pay, soldiers receive a housing allowance, which can go toward either renting or buying a home. With a VA certificate, they can purchase a home with no down payment and a lower-than-market interest rate.

And in the Killeen metropolitan area, where the median home price is only about 68% of the national median, even the lowest-ranking soldier can afford to buy.

"If I'm an E4, and I'm making barely enough to survive, I can still buy a home and have my boss pay the mortgage," says John Driver, who served as operations director for Fort Hood's housing division from 2002 through 2016.

In addition, the military can ease one of the barriers to homeownership that African-American people too often face in the rest of the country: Expensive credit. Many studies have shown that black and Hispanic people have a harder time getting loans and face higher interest rates if they are approved.

Lenders don't give the troops much trouble, especially in a place as diverse in Killeen. "They still scrutinize, but they know that if a person has that [VA] certificate, then they have the means to pay that monthly mortgage," Driver says.

According to lending data obtained through the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, 72.9% of home loans in Killeen were financed by the VA in 2016, compared to 11.2% nationwide.

There are some downsides. Killeen's abundance of single-family homes, which are still mushrooming in subdivisions across the scrubby rolling hills, keeps real estate from appreciating very much. So houses in the city aren't as good of an investment as those in hot markets like Austin.

But in Killeen, the military offers other routes to prosperity. In exchange for their commitment and potentially putting their lives at risk overseas veterans enjoy tuition benefits through the GI Bill, as well as preferences for small business loans, government jobs, and federal contracts, which can be quite lucrative.

"The way to really build black wealth is to go into the military in your 20s, and get all your education," says Gregory Johnson, a veteran and real estate investor who serves on Killeen's city council. "Then you come out and you can roll into these jobs, and you're drawing thousands of dollars per month."

Related: The financial impact of winning (and losing) the birth lottery

And veterans tend to stick around the area. According to the Heart of Texas Defense Alliance, a non-profit coalition of Fort Hood-area governments and businesses, about 85% of local retirees remain within the region; 295,000 veterans and their family members now live in the Killeen area. It's a convenient place to retire, with a large VA hospital nearby, and each of Texas' major cities within a few hours drive.

In addition, the relative economic parity that Fort Hood fosters between the races also supports integration and harmony that other places lack, longtime residents say. It's easy to find a black real estate broker or a black dentist, and the walls of the hospital are filled with portraits of black physicians. With few private schools, everyone's kids end up in the same classrooms — a far cry from educational segregation in big Texas cities like Houston.

"It's the only city I know where there isn't a 'white neighborhood' and a 'black neighborhood,'" says Ross Caviness, an insurance agent who's lived in Killeen since 1982. "They'd have Klan rallies in Waco. And they still do. But I think Killeen is like an island. You just don't feel the racial tension."

Of course, that doesn't mean Killeen doesn't have its share of problems. There are neighborhoods with housing in bad condition, and the poverty rate is about average for Texas, higher for black people than for whites.

But for thousands, like Jones, the military and Killeen offered a ticket to financial security that employment in the private sector so often doesn't, especially for African Americans. "Jobs were difficult in the 1960s and the 1970s. And so I took the easy way out," Jones says.

It wasn't really easy, he admits — after four tours in Vietnam, Germany, Japan and Korea, he was left with PTSD that still sometimes haunts him. But eventually, it paid off.

"I had a roof over my head. I could feed my family. I was able to purchase an automobile. Unless they shut down Fort Knox, I knew that I was going to get a paycheck," Jones says. "And now my children are grown and gone, my grandchildren are grown and gone, I have great grandchildren, and they can come to Pawpaw's house. And I'm ok with that."