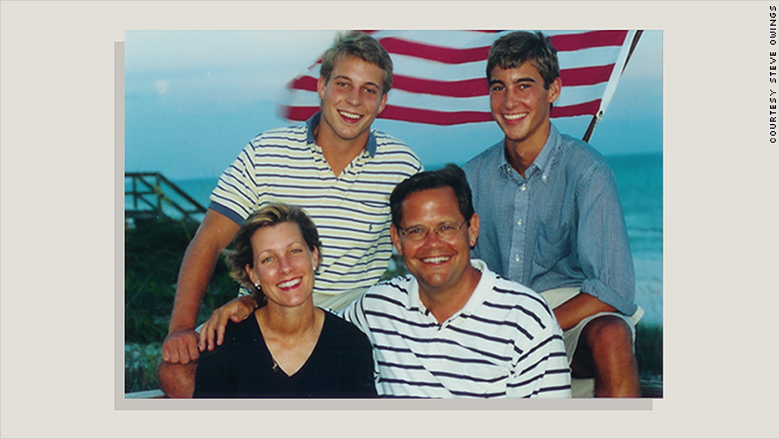

It's been 15 years since Steve Owings lost his son to a speeding tractor trailer, which barreled into the college senior's car while he was on his way back to school.

Ever since, Owings has been pushing for a new federal rule that would require devices limiting large trucks to a top speed of 65 miles per hour. The American Trucking Association, representing most of the industry, agreed; most new trucks already had built-in speed limiters.

The Obama administration came out with a draft version in 2016, and went through the required comment period.

Finally, Owings thought, Washington might do something to help prevent accidents like the one that took his son's life. According to the US Department of Transportation's own research, limiting truck speeds could save between 63 and 214 lives per year.

"If ever there was a layup, this is it," Owings says.

And then, the unfinished rule hit a red light.

As one of his first official acts in January 2017, President Donald Trump announced Executive Order 13771. The order said that for every new regulation, two need to be relaxed or tossed out. On top of that, agencies have to reduce the total cost burden of the regulations they impose on businesses, non-profits, and governments.

In 2017, the agencies could impose no net new costs. In 2018, costs need to be reduced by at least $686 million, according to targets set by the White House's Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

But cutting red tape is easier said than done. Many of the Trump administration's attempts to get rid of existing rules with a big financial impact have ended up getting tied up in the courts. If agencies can't win major cost savings by cutting back, finalizing new rules — even ones that businesses favor, like the one limiting truck speeds — becomes much more difficult.

Owings sits on an advisory committee that tried to come up with old rules to cut in order to offset the cost of the speed limiter rule, but they couldn't name many.

Under the rubric set up by Executive Order 13771, the speed limiter rule would be expensive. The Department of Transportation's original analysis had determined that it would cost between $200 million and $1.5 billion annually due to slower delivery speeds, but the executive order's scoring system doesn't count the benefits to truckers, such as better gas mileage. Last year, the Transportation Department stalled the rule indefinitely by putting it on its long-term agenda.

A spokesperson for the Transportation Department confirmed that the rule is still under review. The department also noted that while it takes the executive order's guidance into account, it still assesses every rule on its own merits.

To Owings, the order feels like an almost insurmountable hurdle. "There are plenty of regulations that can be improved, but it's very difficult to find regulations that can completely be eliminated," Owings says. The two-for-one requirement "really just kind of shut things down, which I guess was the goal."

Savings vs. societal benefits

That's exactly what advocates for causes like consumer and workplace safety and the environment are worried about. They say Trump's anti-regulatory regime will prevent agencies from issuing new rules to address health and safety threats, or set guidelines for nascent industries, like commercial space flight and autonomous vehicles.

"Will they be able to undo many existing rules? No," says Peg Seminario, director of occupational safety and health at the AFL-CIO. "But I think the big focus for the industry is that they didn't want any new rules. I think the main impact of this will be to stop progress."

Related: The surprise winners of the bank regulation rollback

To be sure, regulators are hard at work finding rules to scrub. In 2017, federal agencies racked up 22 deregulatory actions for every regulatory action. While most of the 67 deregulatory actions were relatively minor, the White House estimates they will save businesses a total of $570.4 million a year.

Trump has talked up these initiatives at rallies with his supporters. Deregulation "hits home in parts of middle America, where folks are struggling and businesses have been shut down and folks are looking for work," Anthony Campau, the chief of staff at the White House's Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, said last month. "The president, when he says these things, he gets standing ovations."

That apparent progress, however, may not be sustainable — or even as impressive as it sounds.

In 2017, the Trump administration had a big assist from Congress, which swiftly undid 15 recently-passed rules using the Congressional Review Act. They included everything from a rule making it harder for mentally ill people to obtain guns to another protecting Internet users' privacy.

The window to use the Congressional Review Act on rules enacted during the Obama administration has since closed, meaning agencies will have to go through a much more drawn out process in order to meet their regulatory cost targets.

In OIRA's spring 2018 Unified Agenda, 631 rulemakings were subject to the president's executive order. Nearly three out of four were deregulatory, meaning they will weaken, delay or withdraw a rule rather than establish one. According to the right-leaning American Action Forum, following through on all of those plans would save $1.4 billion annually — about twice the administration's 2018 goal of $686 million.

Industry groups are behind many of these efforts, both big and small. After years of lobbying and litigation, for example, wealth management firms won nearly $1.5 billion in regulatory cost savings last year when the Department of Labor delayed the implementation of a rule requiring financial advisers to consider their client's interests before any commissions they might earn.

Related: Trump official: Regulators don't have a 'blank check'

Other deregulatory actions on the agenda include changing the type size for calorie declarations on snacks sold in vending machines and weakening the Environmental Protection Agency's authority over rivers and streams.

But the bulk of the rules underway — nearly 1,600 of them — are exempt from Trump's executive order, including those with a defense or national security purpose, those having to do with agency personnel and management, and those issued by independent agencies like the Securities and Exchange Commission.

That's why some scholars don't see the executive order as the cost-cutting red tape killer that the administration made it out to be.

"They're talking about this stuff as if it's hugely significant to the economy, has the potential to boost growth in a serious way," says Philip Wallach, a senior fellow at the libertarian R Street Institute.

He points out that the $570.4 million a year saved through deregulatory actions in 2017 is peanuts in the grand scheme of things. "It's kind of hard to understand how those numbers match up with the claims of really having taken deregulation to the point where you're setting businesses free," says Wallach.

Defenders of the White House's approach counter that the economic gains from clearing the path for business could have a cumulative impact, which isn't easily captured in a cost-benefit analysis.

"If actions being taken by the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration will eliminate or modify old rules that are getting in the way of autonomous vehicles, the cost savings might be small, but the potential gains to the economy are enormous, because they're eliminating barriers to innovation," explains Patrick McLaughlin, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

McLaughlin also points to the United Kingdom and the Canadian province of British Columbia, which have established "regulatory budgets."

But those differ from the White House's order in one big way: They take into account a rule's societal benefits, not just its costs. Although an earlier order requiring complete cost-benefit analysis remains on the books, Trump's executive order does not consider the potential economic benefits of a regulation — such as cleaner air, fewer deaths from roadway accidents and better wages for the lowest-paid workers.

Red tape on red tape

That's partly why many of the administration's biggest attempts at deregulation are tied up in the courts. Environmental groups have challenged most of the Environmental Protection Agency's major rollbacks, and public interest groups are fighting the administration over the legality of the executive order itself.

Sometimes even businesses themselves want regulation. Farmers represented by the Organic Trade Association, for example, sued over the withdrawal of a final rule that would have put greater restrictions on livestock care and slaughter. "The continued success of the organic sector demands that organic standards be robust, consistent and clear in order to stay meaningful," the group said.

Roncevert Almond, a lawyer who represents aviation and space clients in regulatory matters, says setting uniform rules of the road where few exist would help create certainty for emerging industries, like commercial space flight.

"At every National Space Council meeting, all they're talking about is 'how can we deregulate or streamline,'" Almond says. "And the problem is, you can't streamline what doesn't exist."

There's some irony in this regulatory battle. Environmental and worker advocates have long bemoaned the hurdles that get in the way of making new rules. But now, those same hurdles are protecting some of the rules they fought hard to win.

"Conservatives are facing this problem: Getting rid of a regulation requires a regulatory action," says James Goodwin, senior policy analyst with the left-leaning Center for Progressive Reform. "They have to go through the very same process."

Related: 10 years after the financial crisis, have we learned anything?

What's more, many rules are difficult or even impossible to wipe away without congressional action because they are spelled out in sweeping and long-established laws, like the Clean Air Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Neomi Rao, the conservative law professor whom Trump appointed to head OIRA, said at an event at the Brookings Institution that president's goal of cutting the Code of Federal Regulations to 20,000 pages, which is how long it was in 1960, is impossible without legal changes.

"The growth from 1960 to today is largely based on a number of statutes that have required a lot of regulations," said Rao. "So you'd have to work with Congress in order to get back to those levels."

Republicans in Congress are now taking aim at some of those statutes, but it's slow going. In the meantime, Owings is still waiting for the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration to require the use of speed limiter devices on trucks, as the number of deaths caused by truck crashes each year keeps growing.

"If someone explained all this to the president, I think he'd say, 'Of course, do that, are you kidding me?'" Owings says. "Yet we're in this quagmire of a process that just doesn't work. It's negligent and it borders on criminal."