With unemployment near historic lows, there seems to be just one missing piece in the economic recovery: Wage growth.

Take-home pay picked up in 2015 and 2016, but it has since flattened out at annual growth rates that remain substantially below the 5% that workers enjoyed prior to the Great Recession.

There are lots of theories for why that's the case. But there are also lots of different ways of looking at wages themselves, and each data set can tell a different story.

Here are a few ways that the federal government measures compensation and what they show us about Americans' financial well-being.

Real weekly earnings for all workers remained flat for the year

The Bureau of Labor Statistics' Current Employment Survey publishes data on the private sector, or about 85% of workers. Taking all of those workers and adjusting for inflation, average weekly earnings rose 0.3% in May to $928.74, from a year earlier. But that increase is largely because the number of hours people worked went up by the same amount.

Earnings had improved in 2014 and 2015 — in part, because workers were putting in more hours — but then they stopped short and have been relatively stagnant ever since.

For workers who don't manage others, earnings growth has slowed

When taking a look at production and non-supervisory workers, who don't manage other people, earnings have been functionally flat for the past two years.

This data set divides their earnings by the hour rather than the week and found that wages for this group have only risen 7 cents since May 2016, to an average of $22.59 per hour.

By comparison, earnings for all workers, including managers, have grown by 16 cents, to an average of $26.92 an hour.

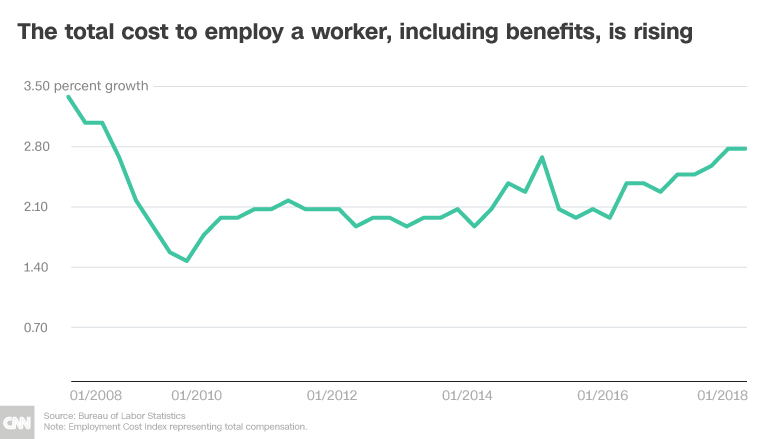

It's getting more expensive to employ people

What ends up in an employee's bank account is only part of what it costs to keep someone on the payroll, however. Over time, wages have made up a shrinking percentage of total compensation.

From an employer's perspective, workers are getting pricier, especially when you take into account health insurance, retirement contributions, paid leave and other benefits.

That's measured by the Employment Cost Index. That report isn't typically adjusted for inflation, which has accelerated over the past year and a half. The increase may be due in part to an increasing number of employers adopting or extending their parental leave policies in response to both legislative and public pressure.

Overall, getting to extremely low unemployment hasn't managed to propel wage growth to where it should be in order to meaningfully improve workers' standards of living.

Related: There are now more job openings than workers to fill them

That mismatch has puzzled economists, although they have proposed some possible explanations: The decline of worker bargaining power, the erosion of labor standards and the high cost of living in big cities that keeps people from moving there for better jobs.

Meanwhile, unemployment is expected to keep dropping through the end of this year, meaning it's not hard to find a job — it's just hard to find one that covers all the bills.