America's birth rate is at its lowest level in three decades. That's a problem for Pampers and Huggies.

Birth rates began dropping in 2008 as the economy sank into a recession. Better access to contraceptives and younger Americans having children later in their lives have extended the decline, the National Center for Health Statistics found.

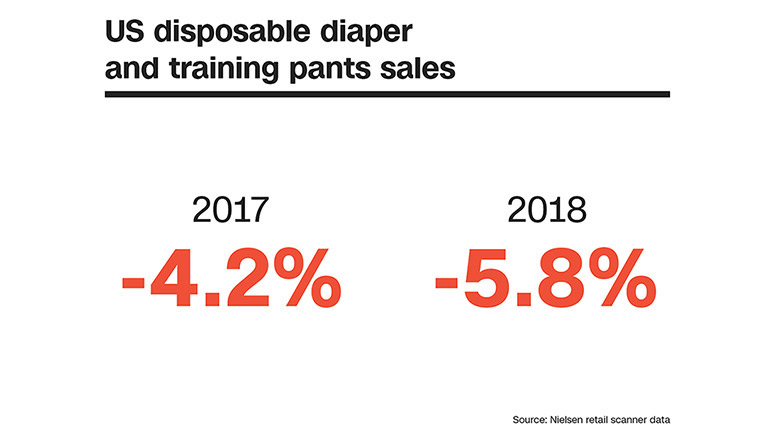

The downturn caused disposable diaper and training pant sales to fall almost 6% from April 2017 to 2018, according to Nielsen's most recent brick-and-mortar retail scanner data.

"This new reality is beginning to take a substantial toll," said Svetlana Uduslivaia, the head of industry research at Euromonitor International. The diaper slump will probably be the "normal for the foreseeable future."

Diaper wars

Fewer babies mean falling sales for Procter & Gamble (PG) and Kimberly-Clark (KMB), the country's leading diaper suppliers. (P&G makes Pampers and Luvs, and Kimberly produces Huggies and Pull-Ups training pants.)

In January, Kimberly said it would lay off around 13% of its workers and shutter 10 manufacturing plants to save money in the pinch.

"You can't encourage moms to use more diapers in a developed market where the babies aren't being born," chief executive Thomas Falk told analysts.

Related: The maker of Huggies and Kleenex is cutting thousands of jobs

Diapers are key businesses for both companies.

Huggies or Pull-Ups account for about a third of the company's $18 billion in sales, according to AllianceBernstein analyst Ian Gordon. (Kimberly does not break out diaper sales.)

Pampers are P&G's top-selling brand, bringing in more than $8 billion a year. The conglomerate's baby care unit was its second largest business in 2017. It made up 14% of P&G's $65 billion worth of sales.

Huggies and Pampers have cornered the market by convincing parents that their diapers are the safest and most reliable for newborns and toddlers.

Last year, P&G controlled 43% of the market and Kimberly grabbed 35%, according to Euromonitor.

"Parents are extremely brand loyal when it comes to products for their kids," said Morningstar analyst Erin Lash. "If a diaper works and you don't have accidents or issues when you're out with your child, you probably will stick with it."

The rewards of retaining shoppers are huge for diaper makers.

Related: Meet the guy Walmart is betting $3.3 billion on to fight Amazon

"If you have multiple children, and it works for one kid, you're going to start there for your second child," Lash said.

Diapers are also a profit windfall for the companies because they're expensive and parents repeatedly need to restock.

"There aren't as many expenditures for a household as big as diapers," said Leonard Lodish, a professor emeritus at the Wharton School of Business and an early investor in Diapers.com, the online startup founded by Marc Lore.

Parents can spend more than $700 on diapers for babies during the first year of their lives, Uduslivaia said.

Pampers Pure

P&G has taken several successful steps to respond to the demographic changes.

The company has extended its reach to parents concerned about diaper materials and ingredients.

In February, it unveiled Pampers Pure diapers and wipes, a "natural" collection with zero fragrance, lotion or chlorine. Pampers Pure will compete with Unilever-owned Seventh Generation and Jessica Alba's startup Honest Company, brands that have gained traction with eco-friendly marketing.

Related: Jessica Alba's Honest Co. just got a $200 million lifeline

Pure has already become the top-selling natural diaper, P&G's chief financial officer Jon Moeller said at a conference this week.

The brand is more expensive than P&G's regular line, but raising prices is difficult.

Promotions and discounts are a staple of diaper marketing, and shoppers want to save money on big-ticket purchases. Retailers, under pressure to attract shoppers, want to hold the line on prices.

"If you are going to raise the price, you have to justify why," Uduslivaia said. "What is so unbelievably great about that diaper that people would be willing to spend more?"

P&G has also focused more on faster-growing areas: pant-style diapers for toddlers and Always Discreet, an underwear line for women with bladder issues.

And it has overhauled its diaper business in China.

Pampers missed Chinese consumers looking for solely the most absorbent diaper to finding ones that were also softer and more aesthetic. "We were in many ways irrelevant" Moeller said.

But P&G poured resources into improving Pampers' premium diapers and pants in China. It's now projecting to grow the brand for the first time in four years.

Pampers' re-emergence comes right in time: China is scrapping its one-child policy.

Mama Bear

To add to the challenges, P&G and Kimberly are also grappling with retailers' private labels and Amazon.

"The market is changing and some customers are aggressively pursuing private label," P&G CEO David Taylor said in April.

Private label brands are as much as 20% cheaper — a threat to Luvs, P&G's value line. P&G has responded by lowering Luvs' prices, but that hasn't stopped the bleeding.

"The lower private-label pricing has been a real challenge," Taylor said. "While we've taken some steps to restore Luvs' competitiveness, it hasn't had the desired effect yet."

Kimberly, looking for ways to fuel growth, has turned to a risky source: Amazon.

Amazon quietly added diapers to its Mama Bear baby line for Prime members last year, and analysts confirmed that Kimberly is manufacturing the label. (Both Kimberly and Amazon declined to comment.)

Although Mama Bear will compete directly with Huggies, Kimberly has decided that strengthening its private label offerings is the best choice.

"In a tough, competitive environment, where it's really hard to grow organic sales, why not?" said Uduslivaia. "If they don't do it, somebody else will."

For Amazon, its the company's second crack at diapers. It launched Amazon Elements diapers in 2014, but quickly pulled them after poor reviews.

But the company has attracted shoppers in recent years with Amazon Family, an online subscription service that offers 20% off diapers and baby food.

Amazon has found that many parents prefer ordering diapers online more than going to the store every time they run out.

"It's a pain in the neck to keep replenishing them," Lodish said. "They're big and bulky and you don't want to buy them and have to schlep them home."