When Laura Pedersen opened her clinic for young pregnant women in Tucson nearly 20 years ago, her job seemed overwhelming — around 12,000 babies were born to teens in Arizona a year, with all of those young moms requiring special counseling and support. The program, called Teen Outreach Pregnancy Services, even opened a second location in Phoenix to keep up with the need.

But 18 years later, demand has fallen off a cliff. In 2016, fewer than 6,000 teens gave birth in Arizona.

"We have definitely experienced a decline in the number of referrals," Pedersen says. "There's not as great a need for our services."

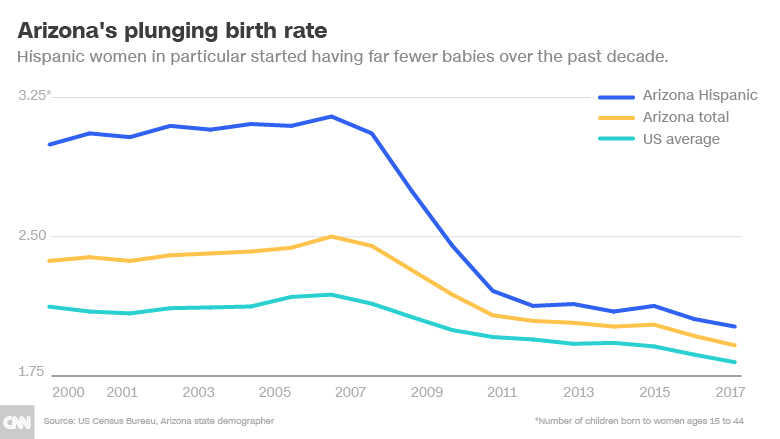

Arizona, which in the early 2000s had one of the highest fertility rates in the country, saw the largest decline in the number of births of any state over the past decade. It went from nearly 103,000 births in 2007 to about 81,000 last year — a 20% drop.

What's happening in Arizona is an extreme example of a wider trend occurring across America. The "total fertility rate" in the United States, representing the number of kids the average woman will have in her lifetime, sank to an estimated 1.76 in 2017, down from 2.12 in 2007. (This isn't the lowest point, however. The nation's birth rate reached 1.74 in 1976, after a huge spike from the Baby Boom, when American women had more than three kids each on average.)

Related: the US economy needs seniors to work longer. Here's how.

So what's going on?

According to economists and fertility experts, it's a combination of factors.

First, the recession sucked away resources needed for supporting families, like stable housing and money for child care, causing many families to think twice about having kids. Meanwhile, improved sexual health education and access to birth control has helped reduce teen pregnancies. Ramped up immigration enforcement by federal and state governments has deterred women of child-bearing age from crossing the Mexican border, and they have fewer kids after they arrive.

The falling birth rate has some experts worried that America will be left with too few people of working age to support its burgeoning elderly population — both by paying into programs like Social Security and by filling jobs in fields such as health care and home assistance.

"If we stay at 1.76, it's not a huge issue," says Bradford Wilcox, director of the National Marriage Project, a nonpartisan research group at the University of Virginia that examines trends in family and childbearing. "If we continue to see a decline in fertility, that would be more likely to lead to some important social and economic challenges."

That's why it's important to keep an eye on Arizona, where the recession and a crackdown on immigration have created a generation that will be much smaller than those that have come before.

Immigrants hit hard

To put Arizona's baby bust into context, it's important to understand its boom.

In the 1990s and into the 2000s, Arizona's fertility rate hovered near 2.4 children per woman, while the US average stayed between 2 and 2.1. However, the Hispanic birth rate in Arizona was much higher, at 3 children per woman in 2006, with foreign-born Hispanic women pulling up the average.

Tom Rex, manager for research initiatives at Arizona State University's Office of the University Economist, says that's largely because Arizona was drawing in so many Mexican immigrants for work in tourism and construction.

The financial crash hit Arizona's red-hot real estate industry particularly hard, causing thousands of immigrant families to lose their primary source of income. According to the 2006 American Community Survey, 37% of foreign born women of childbearing age in Arizona had a spouse employed in construction. In 2016, that figure was down to roughly 27%.

Fertility usually starts falling right before a recession hits, which economists have theorized might cause an impending sense of economic insecurity among families that prompts them to put off the financial burden of having kids. Arizona's large immigrant population, which was largely employed in recession-prone economic sectors and had higher-than-average birth rates before the recession, magnified that effect.

But something else was going on in Arizona that was different from other heavily Hispanic states, like California and Texas. In 2007, the legislature required employers to verify their workers were in the country legally using the federally run E-Verify system. Employers who use E-Verify submit their employees' personal information online, where it's then checked against information in databases at the Social Security Administration and US Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Related: In Arizona, the mandated use of E-Verify has had mixed results

The state cracked down even harder in 2011, when it passed S.B. 1070, allowing police to ask for proof of citizenship during stops for minor infractions. According to one study by economists Mark Hoekstra of Texas A&M University and Sandra Orozco-Aleman of Mississippi State University, S.B. 1070 alone reduced the flow of undocumented immigrants by more than 30%.

By 2017, Arizona's Hispanic total fertility rate was down to less than 2 births per woman.

"[The laws] could've had morale effects for Hispanics in Arizona in terms of not wanting to have as many kids because things were uncertain," says Jessamyn Schaller, an assistant economics professor at University of Arizona.

Schaller analyzed data from the National Center for Health Statistics and found the number of births to foreign-born Hispanic women fell by more than half between 2006 and 2016, with most of the decline occurring during the recession.

More prevention, fewer kids

While economics and politics drove Arizona's birth rate down swiftly, longer-running social forces were at work as well.

Birth control has become more widely available and socially acceptable, especially after the Affordable Care Act was put in place in 2010. Obamacare not only required insurance plans to cover birth control, but also provided grants to states to boost teen pregnancy prevention programs.

Crystal Cortes, 27, has seen both of those forces at work in her own life.

A daughter of conservative Catholic Mexican immigrants, her family didn't teach her about sex and the public high school she attended in Tucson taught abstinence as the only form of birth control. At age 17, she ended up getting pregnant and decided to keep the baby.

But she credits Teen Outreach Pregnancy Services' programs with helping her avoid getting pregnant a second time. Now on the board of the organization and a neonatal nurse herself, Cortes thinks that girls today have more options.

"If girls really want to take a stand for their reproduction, they can," she says. Meanwhile, she's planning to hold off on having another child, which she feels is more in line with middle-class American life.

"Coming in here and trying to figure out the American dream, I think that's part of it, a smaller family," Cortes says. "I think that's actually financially smarter than having too many kids that you can't provide for."

What happens when less babies are born?

Having fewer babies can carry consequences for industries and governments.

Longer term, employers may start having a harder time finding workers, especially if more immigrants aren't allowed into the country. While Arizona's population is still growing as more people move into the state, the construction industry is already experiencing labor shortages, as is healthcare, where staff needs are mounting as the population ages.

But there are fiscal benefits, too. According to Jim Chang, Arizona's state demographer, public school grade sizes are starting to shrink, which could mean that the education system will need to contract in coming years. The state will also have to pay less for Medicaid for poor children.

"Clearly, it will take pressure off the welfare system if women have delayed childbirth and they're in the labor force," says Elliott Pollack, a Scottsdale-based economics consultant.

Since most of the decline in Arizona's births were likely unintended pregnancies, the state's children may be better prepared for success in the future, says Elizabeth Wildsmith, a family demographer at Child Trends, a non-profit research group that studies youth well-being.

Related: How do you talk about fertility at work?

"The evidence suggests that kids tend to do better when they're born into situations where they're a little bit more stable and that is more likely to be the case when parents are able to finish school and be in jobs that have higher wages," she says.

The only danger on the horizon: The Trump administration has shifted US health education programs to emphasize abstinence only, and has also proposed a rule change that would cut off funding to any organization that provides information about abortion.

Teen Outreach Pregnancy Services is one of the groups that depends on federal funding, and is now struggling to bring in even enough money to serve its reduced caseloads. Its two offices will have to downsize, and the organization is planning to merge with another in order to avoid shutting down completely.

"As long as there are still teens getting pregnant, they deserve to receive health education and supportive services," says Pedersen. "There is still work for us to do!"

Correction: An earlier version of this article misreported Bradford Wilcox's first name and misidentified the university Jessamyn Schaller works for.