Programming note: Go back to the decade that's responsible for your smartphone and social media addictions: 'The 2000s' airs Sundays at 9 p.m. ET/PT starting July 8 on CNNTV and CNNgo.

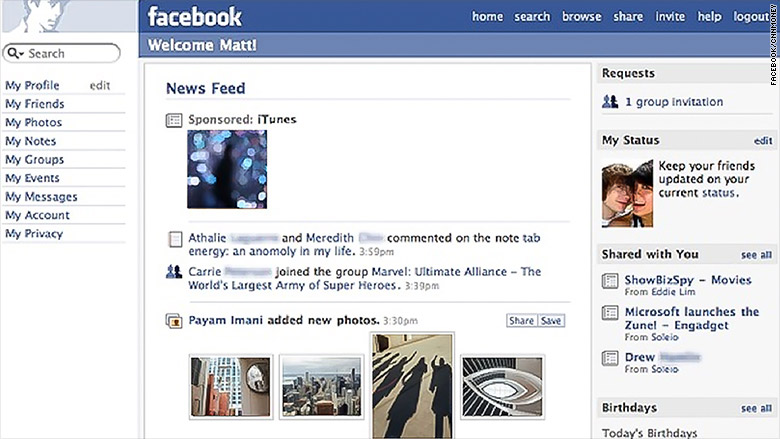

During a six-month period in 2006, two pivotal events helped upend the internet as we knew it: Twitter launched in March and Facebook announced News Feed in September.

The two services introduced the social media news feed to a mass audience, changing how we engage with friends, consume news and view the world. These never-ending streams of updates are curated at least in part by opaque algorithms designed to personalize content and keep you scrolling, scrolling, scrolling so you see as many targeted ads as possible.

Feeds proved to be the death knell for the bygone era of web browsing, when people surfed the messy, often chaotic internet one URL at a time. "This is how the Wild West was tamed," says Ramesh Srinivasan, a professor at UCLA who studies the impact of technology on society. That led to a radical shift in how people consume information. Rather than deliberately scouring blogs, forums and news sites, "information is finding us, but we don't know how," Srinivasan says.

At its best, this shift sparked and supported new relationships, viral social good campaigns and pro-Democracy movements like the Arab Spring in 2011. But it also paved the way for filter bubbles, social media addiction, FOMO anxiety, and election meddling. For much of the past two years, Facebook (FB) and Twitter (TWTR) have faced mounting scrutiny over the role their feeds played in spreading fake news and disinformation campaigns intended to sow discord in the U.S. and abroad.

Related: Silicon Valley's 'gut-wrenching' year of confronting its dark side

Looking back, some early employees remain proud of what they built, despite the unintended consequences. "Obviously there's been some really bad stuff," says Blaine Cook, a member of Twitter's founding team. But "the thing we built did what it was supposed to do. It gave communities a voice."

Others sound more resigned.

"Is it net positive?" says Ezra Callahan, one of Facebook's first employees. "I don't know. It is what it is."

Mostly, the consensus among those who built the platforms, and those who criticize them today, is that the rise of the feeds was unavoidable. The surge in people sharing posts online -- a trend that would only grow with the introduction of Apple's original iPhone in 2007 -- necessitated better tools for broadcasting and sifting through all that information. "It was always inevitable," Callahan says. "The feed culture was always going to happen."

The sense of inevitability was so strong in 2006 that people inside Facebook never seriously debated whether to proceed with News Feed, despite ample cause for concern. Employees and a small group of users testing News Feed during its development were stunned to see all the updates about new friendships and breakups and other things occurring across the platform every minute surfaced in one place.

"The initial reaction of so many during testing was, 'This feels like I'm seeing something I'm not supposed to about all these people,'" Callahan says. Some employees worried that Facebook was "just going to take users and throw them into the deep end," as Callahan puts it.

Ultimately, that's exactly what happened. On September 5, 2006, users signed on and discovered the change, which Facebook called a "facelift." Hundreds of thousands of people would soon protest the new feature. CEO Mark Zuckerberg, just 22 at the time, would issue one of his first public apologies in what you could call a foreshadowing of the privacy scandals to come.

While feeds may have taken off no matter what, perhaps some of the worst consequences could have been avoided. Soleio Cuervo, an early Facebook designer, remembers Facebook employees at least briefly teasing the possibility of including a "truth check" for posts in News Feed. The idea, as he recalls it, was that a "yellow squiggly line" might highlight something of questionable accuracy in the same way that a red squiggly line highlights questionable grammar or spelling in Word documents.

The conversation was not entirely unlike the current debate over how best to combat fake news. But at the time, it was a non-starter. "It was an exercise in fortifying our principles," Cuervo says. Those principles included Facebook's fervent commitment to freedom of speech and the "need to be a platform for all ideas, even the ones that are falsifiable."

Meanwhile, the traditional gatekeepers of news were trying to leverage social feeds to expand their audiences. But they failed to anticipate how much this technology would destabilize the media industry by "hoovering up" attention and ad dollars, says Vivian Schiller, the former CEO of NPR who later worked as Twitter's head of news. "There is no way we imagined it would become so profoundly disruptive to the way people engaged with news," she says.

The threat to online publications should have been clearer, given the cumbersome nature of browsing for news online at the time. "The notion of typing in a URL is ridiculous to the user. It's a bad user experience," Schiller says. Facebook and Twitter "created an efficiency for news." But in the process, they created an efficiency for fake news.

Related: Facebook touts fight on fake news, but struggles to explain why InfoWars isn't banned

"There's always been misinformation on the internet, but it wasn't really centralized," says Renée DiResta, who researches disinformation online as the head of policy at Data For Democracy. With social networks, audiences were consolidated in a handful of online destinations. The feeds then served as a perfect pipeline to funnel false information to what DiResta calls a "large, easily manipulatable" audience.

Under pressure from regulators around the world, Facebook, Twitter and other companies are struggling to crack down on fake news and disinformation. That includes using artificial intelligence to battle fake accounts and working with third-party fact-checkers to flag false news. But it may be too late.

"Doing it now, because of Facebook's sheer reach and its sheer power, is going to be very difficult," Cuervo says. If there was ever an ideal time to introduce a tool to fight disinformation on Facebook, he says, it would have been back in 2006, before the feeds changed everything.