In a ceremony last week, President Donald Trump signed a defense bill authorizing $717 billion for more troops and equipment. Buried in the 788-page bill was a provision he didn't mention — one aimed squarely at addressing wealth inequality in America.

Previously known as the Main Street Employee Ownership Act, the mandate was tacked on by Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York. Her goal: Help more workers to own a piece of the company they work for.

The concept of employee ownership has been gaining traction as a way to shrink the gap between people who make money on investments and those who work for a living.

The most common way to do this is through employee stock ownership plans, or ESOPs. Workers pay nothing to participate — the company takes out a loan to buy the shares from the previous owner or shareholders, then divides the shares among the employees. Profits from the employee-owned portion of the company are tax-free, so the tax savings can be used to pay off the loan. As co-owners of the company, employees vote on major events like mergers and spinoffs, but a management team still handles day-to-day decisions.

The average participant in an ESOP today has a share in their company worth $119,691, on top of any other retirement savings, allowing them to build equity in their job just like they might build equity in a house. The company must buy back an employee's shares at fair market value soon after he or she retires or leaves the company.

The plans were formalized by Congress in 1974. While some notable companies, like Wawa and Publix Supermarkets, offer them, they remain a modest part of total American stock holdings, at $1.3 trillion.

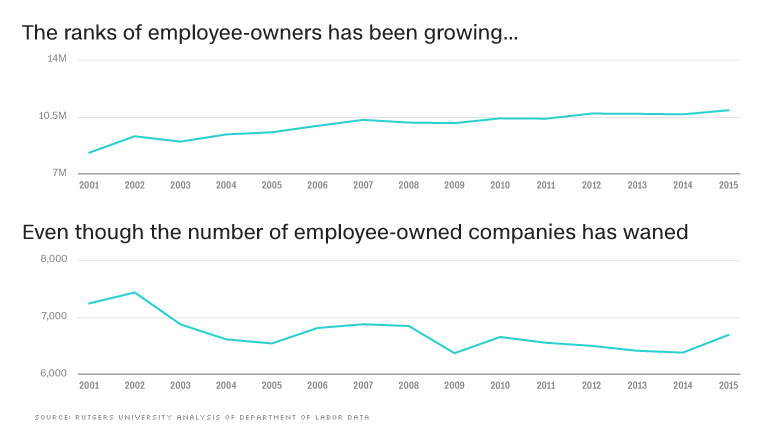

Although the number of workers invested in employee stock ownership plans has risen steadily over the years, the total number of companies offering the plans has actually declined slightly.

And that, scholars and advocates say, is a big missed opportunity.

A professor's proposal makes it into law

America is facing a wave of retirements by baby boomers, who in 2012 (the most recent year for which Census data is available) owned nearly half of the privately-held businesses in America. Many of those will simply dissolve if the owner can't find a buyer or a family member to take it over.

That's why, in early 2017, Rutgers professor Joseph Blasi went to Washington.

Blasi, who directs the school's Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing, has advocated for greater employee ownership for years as a way to level the economic playing field and keep small businesses alive when their owners die or move on. He met with both Republicans and Democrats, hoping that further tax preferences for employee stock ownership plans could be incorporated into the GOP tax plan — something Hillary Clinton had included in her campaign platform — but he got nowhere.

"The bottom line was that the White House was not interested," Blasi says. "They simply wanted to say that cutting taxes for companies will benefit workers."

Gillibrand, however, seized on the idea. She convened a bipartisan group to come up with a plan that could pass, marrying conservatives' sympathy for small business owners with liberals' interest in boosting workplace democracy.

Another key selling point: The package doesn't cost anything. Rather, it directs the Small Business Administration to make its loan guarantee programs more readily available to employee stock ownership plans and worker-owned cooperatives, which often have trouble accessing capital through regular banks. It also makes it easier for a business to transition to worker ownership.

Will the new plan work?

It will definitely help, says Halisi Vinson, the executive director of the Rocky Mountain Employee Ownership Center, a Denver-based nonprofit that helps small businesses convert into employee stock ownership plans. Vinson had hoped the legislation would have created a new department within the Small Business Administration to foster worker ownership, but she says building the expertise at the agency to facilitate loans is a step in the right direction. "Access to capital is the next best thing," Vinson says.

But none of it will matter unless far more business owners learn about employee stock ownership as a succession strategy, advocates say. Kevin McPhillips is the executive director of the Pennsylvania Employee Ownership Center, which was created in 2016 to bolster new worker ownership plans in the Northeast, with help from philanthropies and universities like the Kellogg Foundation and the University of San Diego's Beyster Institute.

"By far, the single greatest enemy to this is awareness," McPhillips says. "From a political standpoint, there's a lot of support. The problem we have is that because everybody likes it, it just can't get the attention of things like defense or crime."

To address the problem, he's setting up a separate organization to scale the idea nationally, with the goal of adding one million worker-owners by 2024. Another initiative funded by Citi Community Development called Fifty by Fifty is shooting for 50 million new worker-owners by 2050.

At one company, employees go 'above and beyond'

These efforts aim to replicate the success of companies like New Age Industries, a family-owned maker of plastic tubing located in Southampton, Pennsylvania. CEO Ken Baker has been handing over company stock to an employee stock ownership plan since 2006, beginning with a 30% stake and gradually adding more. He says it's increased the staff's commitment, reduced turnover, and allowed people to retire with hundreds of thousands of dollars more than they otherwise would have.

"We have a team that walks through walls for the company," Baker says. "When you see employees start doing things above and beyond what they're supposed to be doing, you just smile and say this was the right move."

New Age's employee stock ownership plan now owns 49% of the company, and Baker says he plans to transition the rest when he eventually steps back into the role of chairman, leaving his employees fully in control — a better alternative to selling the company to a larger manufacturer that might not have their best interests at heart.

"It beats what's happening in America right now, with a lot of small companies being sold to private equity and multinationals," Baker says. "Not all of them get destroyed, but many of them do."