The sound you heard Monday was global automakers exhaling.

The preliminary trade agreement reached by the United States and Mexico would rewrite parts of NAFTA and establish stricter requirements for cars sold in North America to be free of tariffs.

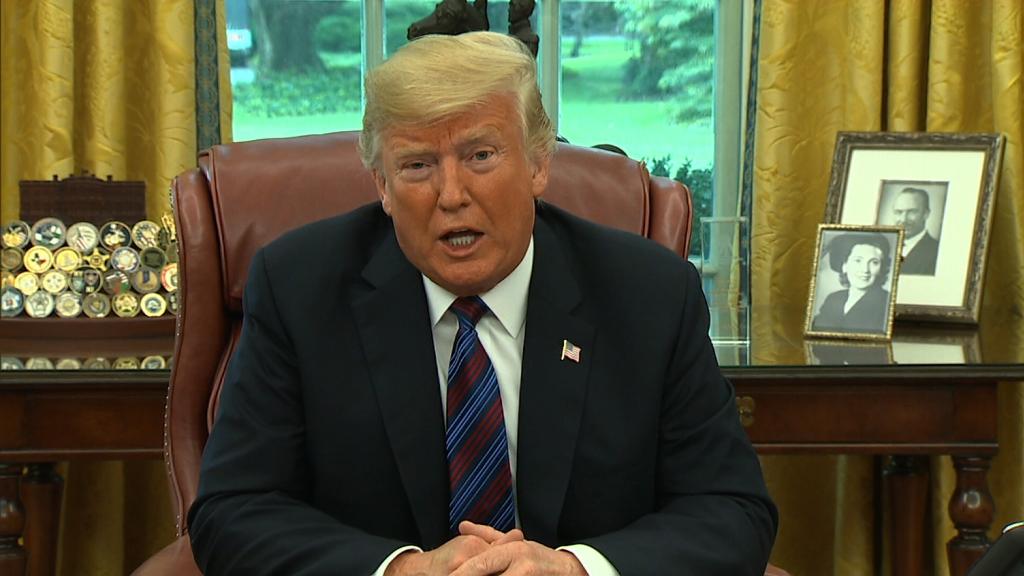

But it would not dramatically change how the car industry does business. That's a win for the industry. The deal, if enacted, would not be nearly as disruptive as what President Donald Trump has long threatened. Trump had said he wanted to get rid of NAFTA, which he claimed had cost thousands of auto jobs.

Trump promised that a new deal would bring those auto jobs back home to the United States. But experts are skeptical about how many jobs will return if the agreement becomes law.

"The supply chain is not being substantially impacted," said Miro Copic, business professor at San Diego State. "It gives the manufacturers the flexibility they wanted."

Investors in US automakers are already showing signs of relief. GM (GM) stock was up almost 5% Monday, and Ford (F) climbed more than 3%.

The new rules outline a couple of major changes that would affect auto companies.

The agreement says at least 40% to 45% of the car must be made by workers earning at least $16 an hour to avoid tariffs when the vehicles are moved across the US-Mexico border.

It also requires that 75% of a car's parts must come from North America to avoid tariffs. That's about 12 percentage points higher than the current threshold.

Experts say the wage provision could tip the balance when automakers are deciding whether to build a plant in the United States or Mexico, but its effectiveness may also depend on how it is enforced.

Matthew Rooney, director of economic growth at the George W. Bush Institute, sees it as a potential "enforcement nightmare."

"[It] leaves a lot of discretion to customs officers, and could be very difficult to manage," Rooney added.

Others say the changes might not matter much, because many of the cars being assembled in Mexico already comply with the new rules. That may have been one of the reasons the Trump administration was able to reach a deal.

"I don't anticipate there will be any major dent in the Mexican economy as a result of this deal," said Chris Garcia, CEO of Vicar Financial, and a former high ranking official at the Commerce Department under Trump.

Executives in the auto industry were huddling on conference calls Monday trying to sort out the details. But they've also been lobbying the Trump administration since its inception to make sure any rules were not as draconian as Trump's original promises.

"This deal is the result of a very concise and targeted advocacy effort to make sure the administration understood the implications of driving too hard a bargain," Garcia said.

Instead, the real losers could be parts plants in Asia or even Europe, because the agreement would require that more car parts must come from North America to avoid tariffs.

"I would think it won't mean any closing of the plants here [in Mexico]," said Gaston Pereira, CEO of the digital finance firm QPagos, based in Mexico City. "In fact the requirement for [more] regional content could mean more investment in Mexican plants."

Still, automakers will have to look closely at their supply chains should the deal go through.

If changing things up would cost more than the tariff on foreign autos, which is around 2.5%, companies may decide to just take the hit and import their cars as foreign vehicles.