Drivers need insurance before they get on the road. And space companies need it before they hurtle metal projectiles into the sky.

Offering insurance for space flight might seem like an insane business decision. The pool of customers is tiny, and the risk is, well, astronomical.

The industry collected $715 million in premiums and paid out $636 million in claims last year, according to an insurance industry expert. That's a slim profit, but margins are known to bloat or thin from year to year. Having a small pool of customers means dealing with volatility.

Yet, it remains a consistently profitable business. A small group of insurance underwriters around the world have racked up expertise that helps the space industry assess risk and write policies.

But a new era of space flight is ushering in drastic changes.

A whole new world of risk

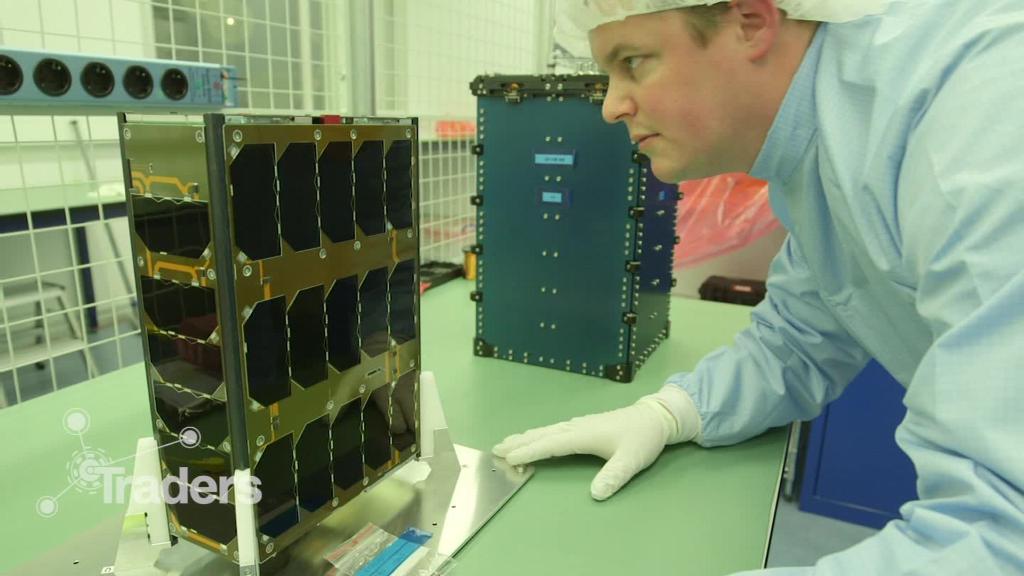

Private companies are driving down the costs of launch vehicles and satellites, making space travel more common.

Insurance for the space industry comes in various forms, including insurance that covers hardware during transportation before launch, insurance that covers launch, and insurance that covers satellites while they're in orbit.

Satellite coverage in particular is about to get a lot more complicated.

Earth's orbit already has a problem with space debris — pieces of junk flying around with no means to control them. They include discarded rocket boosters dating back to the early days of space flight and tiny pieces of shrapnel from a 2007 satellite explosion and a 2009 collision.

Low-Earth orbit, or LEO, is the most crowded area, and companies including SpaceX and OneWeb have plans for new satellite constellations that will put thousands of new devices in LEO.

Space is huge, and collisions are rare. But the more stuff that's put in orbit, the higher the probability of a crash. And the risk doesn't just involve objects that are dead in orbit. It involves potential collisions between active satellites as well.

Satellites can cost a few million dollars on the low end. But companies that operate large communications satellites in geosynchronus orbit — which can be worth as much as $1 billion — are particularly interested in protecting their massive investments from spaceborne projectiles.

That's where insurance steps in. Without it, the satellite operators would have to write off the satellite as a complete loss, potentially cutting deep into its bottom line.

Assessing collision risks is a key piece of what insurers do. Just like in every other field of insurance, the higher the risk is, the higher premiums climb.

Christopher Gibbs, head of space with AmTrust at the insurance company Lloyd's of London, said it's a top concern for underwriters.

"It's something that we constantly talk about," Gibbs said. And if more collisions do occur, "the insurance market will react and premiums will undoubtedly rise."

The broader space community is largely eager to tackle the collision issue. Many in the industry advocate for tougher standards for new satellites to ensure they won't become a dead object in orbit later on. And other startups and researchers have ambitious plans for devices that may be able to move or de-orbit some of the junk in space.

Chris Kunstadter, a senior vice president at XL Catlin (XL), which recently merged with AXA, said insurers are "involved" in a number of those activities. He declined to elaborate.

"Everyone recognizes that it's in their interest to develop solutions to the issue," he said.

The history of insurance

Not all insurance for space flight comes from the private sector. The US government made the crucial decision three decades ago to cover massive amounts of collateral damage in the event of a disaster during a commercial rocket launch.

That insurance doesn't cover the cost of a rocket or valuable payloads — companies still need private coverage for that — but it does cover the potentially cataclysmic damage if, say, a rocket fails and plummets into an urban area.

The government's decision to shoulder that risk was a game changer.

Jim Cantrell, the CEO of rocket startup Vector and an early SpaceX executive, credits that decision with making it possible for commercial space companies to exist at all.

It was a win-win, Cantrell said. Space flight was no longer considered too risky for the private sector to get involved. And it gave the government an incentive to regulate the launch industry to ensure companies wouldn't build reckless rockets.

Fast forward a few decades, and the United States is home to one of the most successful rocket companies in the world: SpaceX. Despite a few mishaps, Elon Musk's rocket startup is running a booming business and beating longtime government contractors for launch awards.

Insurance underwriters who handle the other policies that rocket companies need for launch are comfortable with SpaceX. And other players in the launch game have long track records that make their launches easy to assess.

New rockets

The droves of new space startups amount to a lot of new risks to identify. Every new rocket that enters the market must be meticulously vetted by insurers and federal regulators.

Dozens of new rocket companies have popped up in recent years, and some of them are beginning to enter the market.

Rocket Lab, a US-based venture with a launch pad in New Zealand, completed its first successful orbital flight earlier this year.

Cantrell's Vector plans to reach orbit before the end of the year. And Richard Branson's Virgin Orbit and Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin are planning to debut their own orbital launch technology in the coming months and years.

"That's where companies are made or lost in this commercial business is insuring for their loss," Cantrell said.

Appropriately assessing the risk of newcomers is essential for insurers, but not many of them will threaten to put a major dent in the industry's revenue. The majority of startups, including Vector, are planning to introduce small, inexpensive rockets that will launch relatively cheap satellites.

But with less financial risk comes less reward for insurers.

While the broader global space economy is expected to triple over the next two decades, growing to $1 trillion, the insurance sector grows around 14% — from about $700 million to $800 million, according to a recent report from Morgan Stanley.