No matter who wins the election on Tuesday, the next president will have to immediately stare down the country's largest, most pressing domestic problem: the fiscal cliff.

That cliff -- which starts to take effect in January -- includes $7 trillion worth of tax increases and spending cuts over a decade.

Among the policies at issue are reductions in both defense and non-defense spending, the expiration of the Bush tax cuts, the end of a payroll tax holiday and extended unemployment benefits, and the onset of reimbursement cuts to Medicare doctors.

Lawmakers must choose whether to leave in place some or all of them, replace them, postpone them or cancel them entirely. The decision will affect the economy, the country's credit rating and the U.S. debt burden.

If left in place, the fiscal cliff would lead to the biggest single-year drop in the annual deficit as a percent of the economy since 1969.

But because it would be so abrupt and arbitrary, it also could throw the United States back into a recession next year, when more than $500 billion will be taken out of the economy. (Related: Americans face $3,500 fiscal cliff hit)

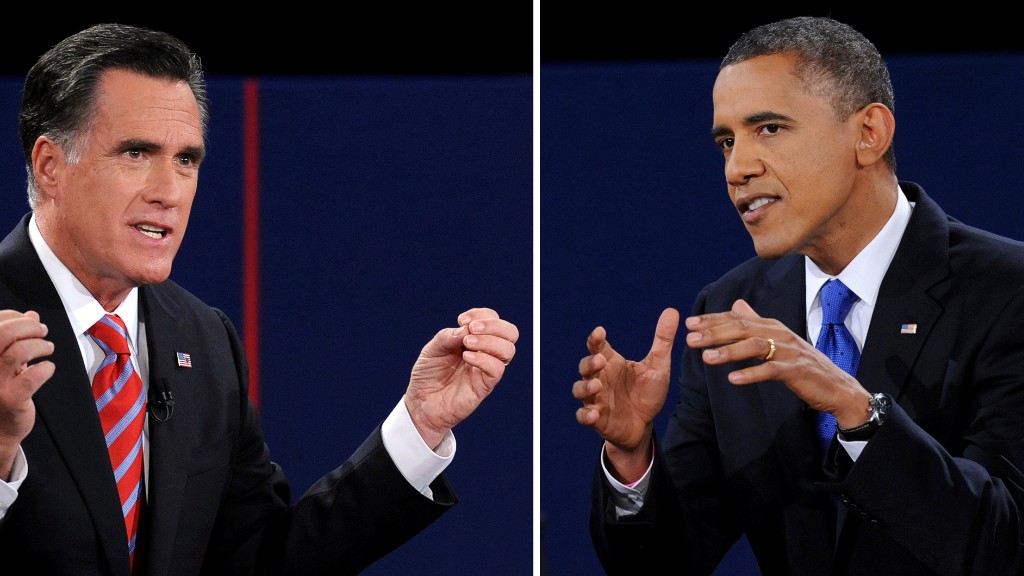

Neither President Obama nor Mitt Romney has said much about the cliff, though each has been vocal on two components: the expiring Bush tax cuts and defense spending cuts.

And neither has said anything about the debt ceiling, which likely would be part of a fiscal cliff deal. The country's borrowing limit will be reached by the end of the year, but the Treasury Department says it can employ "extraordinary" measures to let the government pay its bills in full until early in 2013.

So how would the two men vying for the White House handle things?

Obama: Tax hike on rich key

Like many Democrats and Republicans, the president doesn't like the automatic, across-the-board spending cuts called for under the so-called sequester. He wants them replaced.

At the same time, the White House budget office said the president's senior advisers would "recommend" he veto any bill that averts the defense cuts while leaving intact the non-defense cuts or that "fails to ask the most fortunate Americans to pay their fair share."

Meanwhile, senior administration officials said recently that Obama would veto any fiscal cliff package if it does not include an increase in tax rates for top earners.

The president himself, however, hasn't used the word "veto." Instead, he urges Congress to "work on those things we can agree on" -- namely, to extend the Bush tax cuts for the majority of Americans.

In his last debate with Romney, Obama pointedly said the defense cuts "won't happen" even though both parties -- at least publicly -- aren't budging from their negotiating positions. Then, in an interview with the Des Moines Register, Obama went further, expressing confidence that a "grand bargain" on debt reduction could occur within six months of his second term if he's elected.

Elsewhere, Obama has not pushed for an extension of another key part of the fiscal cliff: the temporary 2% payroll tax cut passed at the end of 2010. But that doesn't mean he won't. "We'll evaluate the question of whether we need to extend it at the end of the year when we're looking at a whole range of issues," Carney said in September. (CNN.com: What to watch for tonight)

Mitt Romney: Give me time

Romney wants time to deal with the fiscal cliff.

In August, Romney told Time Magazine's Mark Halperin that if elected he would rather Obama and Congress postpone the tax increases and spending cuts.

"Let's have at least a year of runway or even six months of runway after the new president is elected so that we can have the tax reform and the military spending plans and the budget plans that are consistent with that individual self-leadership and views."

In May, he said he would want to "deal with these issues on a ... permanent basis as opposed to a stopgap effort that would require unraveling and re-evaluation," he said.

Romney opposes the nearly $500 billion in cuts to defense spending called for under the so-called sequester. And he doesn't want the Bush-era tax cuts to expire for anyone.

At the same time, he has promised to balance the budget in eight to 10 years without cutting defense or raising taxes.

Best-case scenario

Lawmakers and policy experts say the best a lame-duck Congress can probably do before the end of the year is come up with a "bridge" or "framework" deal.

Broadly, that might mean lawmakers postpone fiscal cliff measures for several months to a year, negotiate a small amount of spending cuts and agree to strike a large deficit-reduction deal by a date certain next year, perhaps according to agreed-upon targets for spending and revenue.

But then if lawmakers failed to deliver next year, the fiscal cliff or something similar would take effect.

- Jessica Yellin, CNN's senior White House correspondent, contributed to this report.