Our national debate over economic inequality -- the growing disparity between those with low, middle, and high incomes and wealth -- has evolved in important ways recently.

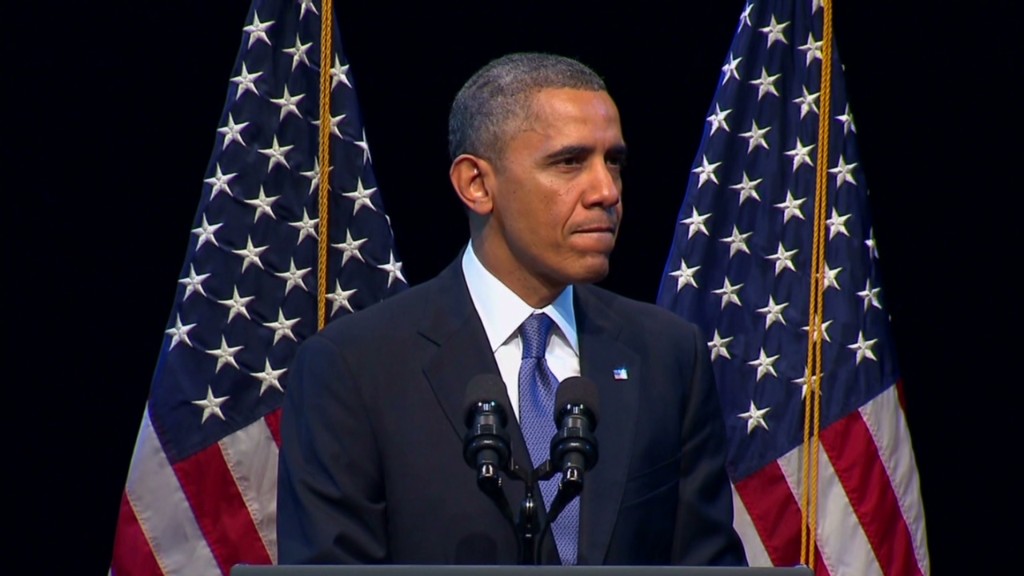

First, by giving a major address on the issue, President Obama elevated it to front-page status. Next, high visibility politicians with very different views than the president on such matters, like Sen. Marco Rubio and Rep. Paul Ryan, also embraced the topic. Sen. Rubio called the inequality trends "startling" and agreed that they "deserve attention."

|

| Jared Bernstein is a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and former member of President Obama's economic team. |

Now, I'll be the first to admit that Washington has been dysfunction junction for a long time now, but I consider this to be progress: Policymakers who agree on almost nothing agree that the level of inequality facing America today is a big problem. The first step to getting better is to recognize you're not well.

Of course, there will always be gaps between the resources of American households at different points in the income scale. There may be some out there who seek equality of outcomes, but I don't know them.

Yet, while we don't always achieve it, most Americans deeply value equality of opportunity.

I believe the reason that policymakers of all stripes are now talking about inequality is that they worry, as do many analysts like myself who've been working on this a long time, that the historically high levels of economic disparity threaten the opportunities of those on the wrong side of the economic divide.

Opposing view: Mobility is the problem, not income inequality

Ask yourself this question: Is America a meritocracy, meaning that regardless of the status of your birth, you're free to go as far as your inherent talents will take you?

It's a question I pose to audiences all the time, and most people recognize that we are not there yet. In fact, we're far from it. Research shows that not only is the correlation between parents' income and education a reliable predictor of how their kids do, but that correlation is higher here than in most other advanced economies.

In other words, while knowing a baby's zip code won't tell you for certain how successful they'll be as a grownup, it tells you more than it should.

But how does this relate to income inequality? First of all, there's a strong, positive relationship between countries with high inequality and that zip code problem. That suggests the two are linked, and that when high levels of income inequality persevere, barriers to getting ahead -- opportunity barriers -- will arise.

Some indicators suggest this process is already at work in the United States:

- There's a wide and growing gap in how much parents invest in their kids. High-income families spend increasingly more on tutoring, art, sports, books, and so on relative to low-income families.

- The academic achievement gap on standardized tests between students for low- versus high-income families has increased by 40% over the last 30 years, the period of rising inequality.

- College attainment has increased much more among kids from wealthy families. The wealthier your family, the more likely you are to go to a top-tier college.

To many Americans, that's why we worry about the heights to which inequality has grown. Not because we begrudge the wealthy their success, but because we want our own kids to be able to realize their economic potential.

And society's growing economic disparities are threatening that most basic aspiration.