Just when you thought the worst was over for Europe, political risk and financial uncertainty could return in 2014.

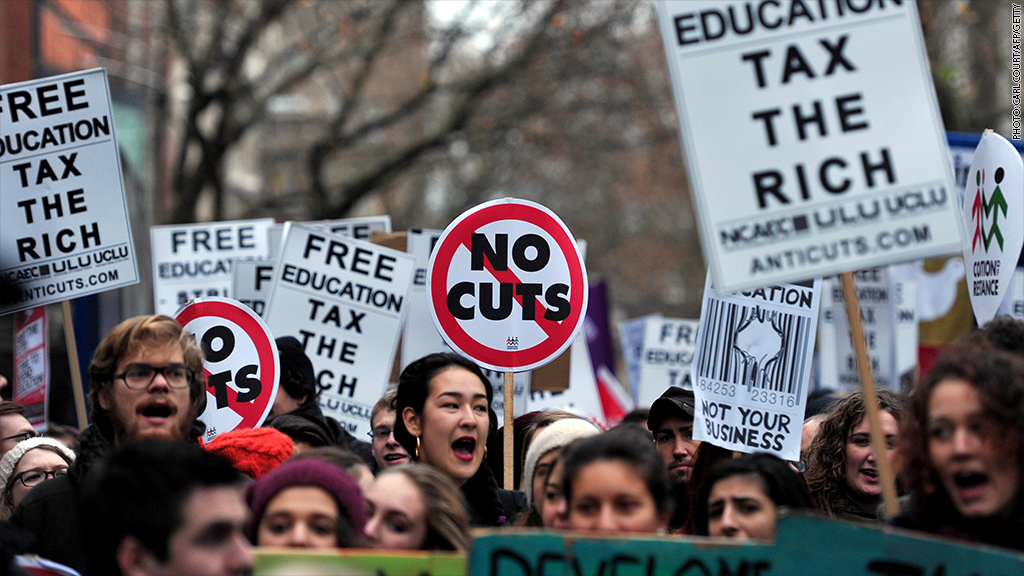

Record high unemployment is giving rise to extremism and some banks may be forced to lean on taxpayers for support.

European Parliamentary elections in May could see strong gains for anti-Europe parties, making it harder to achieve the reforms needed to secure faster growth and create jobs, particularly for the young, business leaders said at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

"The number one challenge in Europe is unemployment," said Accenture (ACN) CEO Pierre Nanterme. "I am extremely concerned about the rise of extremists in Europe -- they're surfing on this lack of inclusion," he said at panel debate hosted by Time magazine.

Europe has emerged from its debt crisis thanks to a series of painful bailouts, central bank action, economic reforms and a pick up in global growth. Investors have responded by buying back government debt, sending yields tumbling from their crisis peaks.

Related: IMF warns of deflation risk

But eurozone growth remains very weak, and is not strong enough to dent record levels of unemployment. Nearly one in four people under 25 are out of work in the eurozone and deflationary risks are rising.

Initiatives, such as a banking union aimed at restoring confidence and boosting investment, are still a work in progress. A new balance of power in the European Parliament could make it harder to complete that project, as well as other reforms aimed at making the eurozone an easier place to do business.

"Think how the Tea Party in the U.S. has complicated political decision-making," said UBS (UBS) Chairman Axel Weber

Related: Europe's lost generation?

A banking union represents the most significant pooling of national power since the birth of the euro. EU leaders had hoped the deal struck in December would be approved by European lawmakers before the election, but that may not happen due to deep divisions.

Weber warned that investors were ignoring another potential risk later this year -- a review of bank assets and stress tests led by the European Central Bank that is due to be completed by November.

"I expect some of the banks not to pass this test," said Weber, a former ECB governing council member, adding that some of those that fail are likely to have to turn to governments for support. And that could resurface concerns about sovereign debt levels.

Related: Pope to global elite: Do more for poor

Without renewed trust in the region's banks, lending to companies is likely to remain crimped, growth will be anemic and unemployment will stay high.

"If radical steps are not taken at a European and country level to break that cycle, we may have not 5 years, not 10 years but 20 years of a mediocre, sluggish situation," Nanterme said.

Harvard economist Ken Rogoff urged Europe to deal more aggressively with the financial legacy of the crisis, by using writedowns and other measures to reduce the debt burden in weaker eurozone states.

"You can't leave the situation twisting in the wind for another five years."