The European Central Bank meets Thursday facing the loudest calls to boost the economy since it last cut interest rates in November.

Last month, the ECB held rates at their record low of 0.25%. But President Mario Draghi warned then it was premature to declare victory in the eurozone crisis, and he promised to use all the tools at his disposal if necessary -- a pledge he repeated 10 days ago.

Economists are divided over whether the ECB will go on the offensive Thursday. Some believe the bank is likely to wait for updated growth and inflation forecasts in March. Others say the time has come. Here's what the ECB is contending with:

1. The risk of deflation

Inflation is slowing in the eurozone, raising the risk of a slide into deflation and stagnation for an economy that is barely growing and still not generating jobs fast enough to bring down unemployment.

Consumer prices rose by just 0.7% in January, weaker than expected and down on December's number. Inflation has now fallen back to where it was when the ECB cut rates in November, and is less than half the central bank's target level.

Draghi has played down the risk of deflation, but the IMF and others have expressed concern that weak prices mean there's little cushion should Europe experience a shock to the system.

Related: IMF warns of deflation risk

2. Shaky growth outlook

Global growth is expected to accelerate this year, thanks to a recovery in advanced economies. But the recent flow of data from the U.S. and Europe has been mixed at best.

Investors took fright this week at a poor reading of manufacturing activity in the U.S. And while surveys in Europe have been more encouraging, retail sales in December were much weaker than expected, falling 1.6% on the previous month.

Emerging markets have been shaken by hints of a slowdown in China, a reduced flow of cheap money from the Federal Reserve, and political unrest. Some have been forced to jack up interest rates to defend their currencies and tackle inflation, moves that could choke off growth and hit Europe's exports.

Related: Investors dump emerging market stocks

3. Market volatility

Investors' appetite for risk has taken a beating recently, as reflected in the flight from the more fragile emerging economies and global stock markets. Traditional safe haven assets such as U.S. Treasuries and German government bonds have benefited, with yields lower than they were a month ago.

Europe's banks are still convalescing, and a sustained period of market volatility may make them even more cautious about lending to households and businesses -- or to each other -- putting the recovery from recession in greater jeopardy.

The overnight interbank interest rate has edged up since the end of 2013, and touched 0.35% last month, before easing back again.

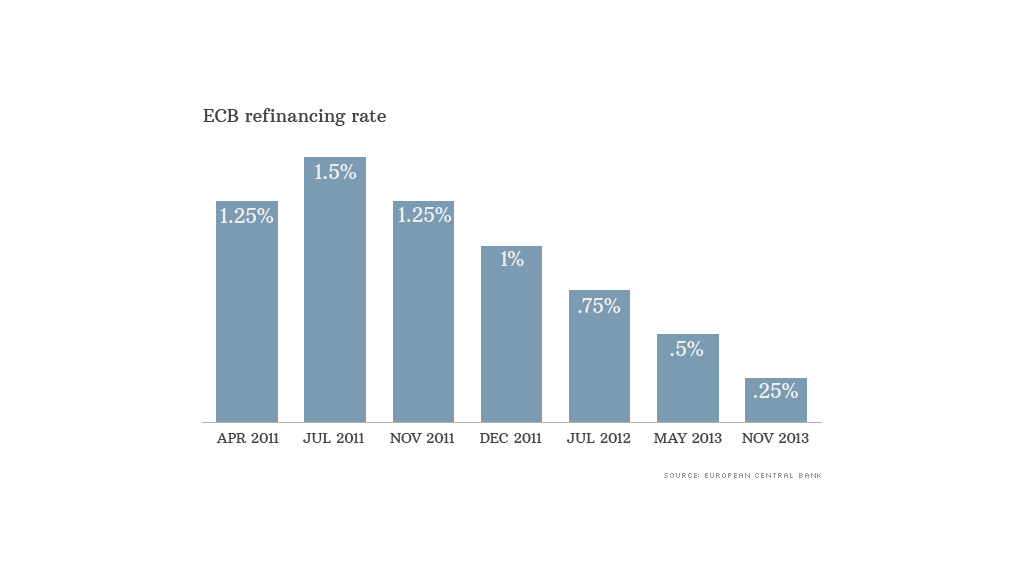

"Volatility has not been welcomed by the ECB in the past and was one of the factors contributing to the refinancing rate cuts in 2013," noted Ken Wattret of BNP Paribas.

So this month, or next, what are the ECB's options?

It could cut the main rate further, perhaps to just 0.10%, take deposit rates into negative territory -- in effect charging banks interest on the reserves they keep with the ECB. Or it could buy packages of bank loans issued to firms and households.

Draghi has indicated that a program of quantitative easing as pursued by the Fed, Bank of Japan and Bank of England, would not be allowed under EU law.