The U.S. dollar is bullying the little guy: emerging markets.

The dollar's rapid rally -- the fastest in 40 years -- is great for the American traveler, but it's painful for many foreign countries and big businesses that operate abroad. Emerging market countries are arguably getting the worst of it.

"Emerging markets are feeling the brunt of the dollar," says Jeff Layman, chief investment officer at BKD Wealth Advisors in St. Louis. "They're getting hit from a lot of different directions."

On top of currency woes, developing countries are also facing political problems, fears of a Federal Reserve rate hike and the commodity bust.

The result is that investors are getting out of dodge. They only put $16 billion into emerging market stocks and bonds in March, according to the Institute of International Finance. Since 2010, emerging markets have averaged much more than that, about $22 billion per month.

Related: 5 travel spots that just got cheaper for Americans

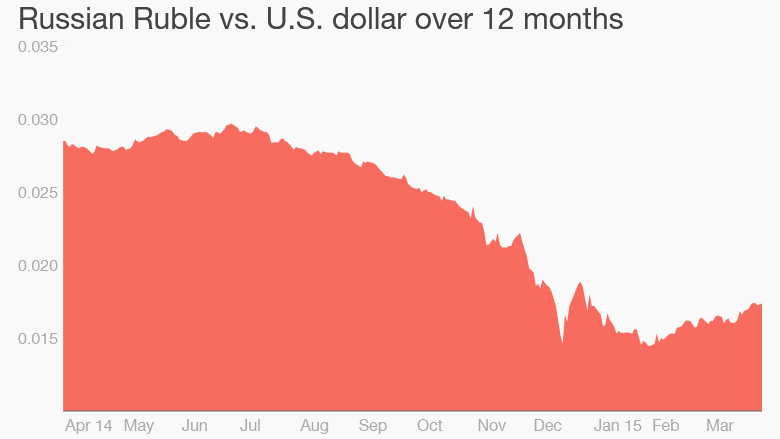

Emerging money's melting value: Emerging market currencies can't keep up with the dollar's speed. The dollar has gained 8% compared to many emerging currencies over the last 12 months, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank.

But looking closer, it gets much worse for some. America's greenback has gained 61% on Russia' ruble, 43% on Brazil's Real and 19% on Turkey's Lira in the past year.

That's a major problem for emerging countries and businesses that have debt denominated in U.S. dollars. Paying off that dollar debt becomes more and more expensive as they pay with their local currency that's losing value fast.

Countries like Turkey, Mexico and Indonesia have 20% or more of their government debt denominated in currency that's not theirs, according to a report by Moody's. That's a lot of foreign debt to pay as their money's value sinks.

For publicly-traded companies, more expensive debt means lower profits and falling stock prices.

When the dollar strengthens, money typically flows to America and out of emerging economies, says Sean Lynch, co-head of global equity strategy at Wells Fargo.

Related: The 2015 bargain: emerging market stocks

Bargain stocks, but maybe not enough: Emerging market stocks are relatively cheap compared to their U.S. counterparts, but the currency loss scares away foreign investors. When they want to convert their profits back into dollars, an eroding currency slashes off some or all of the gains.

The S&P 500 has had a rocky go in 2015, but it's still up 12% over the past year. In contrast, the MSCI Emerging Market Index is down -1.5%.

"The currency -- for the first time that I can recall in many years -- more than offsets the underlying benefit from valuation and growth," Layman says.

Related: What an interest rate increase means for real people

Federal Reserve fears: But it goes beyond the dollar. Janet Yellen might send shivers down spines for emerging market investors.

The Fed is signaling it might raise U.S. interest rates in June or September for the first time in almost a decade. Emerging markets have benefited from the Fed's near-zero rates: investors seeking bigger profits bought emerging market bonds, which have higher interest rates.

Investors already shuddered in fear in May 2013 when then-Fed chair Ben Bernanke announced the Fed would gradually end its stimulus program. Emerging market equities lost 16% in six weeks.

With the markets expecting the Fed to raise rates soon, investors are fleeing high-risk emerging market bonds and moving gradually towards U.S. bonds.

Related: Popular Google search: 'Why are gas prices so low?'

The rest of the problems: The fallback for emerging markets is usually commodities, but not this year. A barrel of oil is a mere $48 today, well below the $100 range it was about six months ago.

That's a big problem for Russia, which is already handcuffed by U.S. economic sanctions.

Beyond oil, a slowdown in China is pushing prices of everything from metals to crops off a cliff. Brazil is hurting from coffee, sugar and soy prices plunging recently. But Brazil has a more scandalous problem -- the huge corruption case involving Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff and its state-owned oil company, Petrobras.

"The things that you're exporting are going down in value...and your liabilities that are in dollars are going up," says James Caron, portfolio manager of global fixed income at Morgan Stanley. "That's a double whammy."