The hedge fund industry's golden age of fat fees and superior returns is over. And the future looks decidedly less fun.

The hedge-fund managers who take home billions of dollars in pay are no longer in denial. There was somber acceptance at last week's SALT hedge fund conference in Las Vegas that fees need to go down.

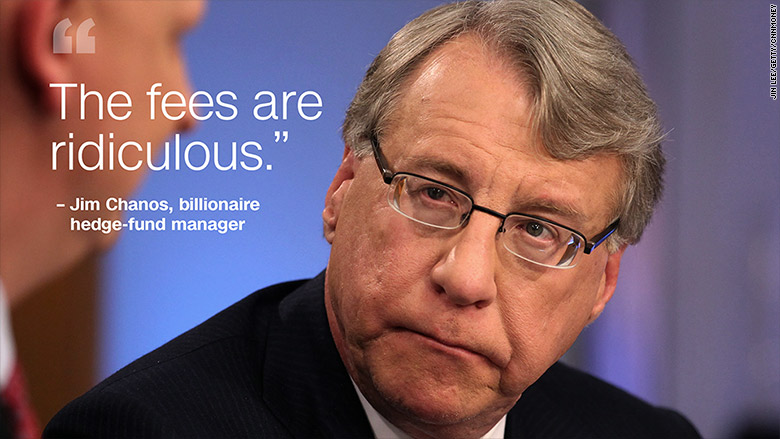

"The fees are ridiculous," billionaire hedge-fund manager Jim Chanos told reporters at SALT, a swanky annual conference held at the Bellagio. "I'm shocked they stayed this high for this long."

And Leon Cooperman, the billionaire founder of hedge fund Omega Advisors, said the $3 trillion hedge fund industry's business model is "under assault."

What's the problem? Hedge funds just aren't crushing it on returns any more. A barometer of hedge fund performance, called the HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index, has generated an annualized gain of just 1.7% over the past five years. Compared to that, the S&P 500's average annualized return for the same period was 11%.

However, hedge funds charge huge fees that eat into client returns. The standard fee structure, known as "two and twenty," calls for a flat 2% fee on total assets managed and an additional 20% on profits earned.

Related: Hedge fund kings made less last year

Now hedge funds are facing a revolt from the asset managers who used to steer vast sums of money their way. For example, in 2014 the largest U.S. pension fund, the California Public Employees' Retirement System (CalPERS) ditched hedge funds entirely.

Roslyn Zhang, managing director of the massive sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation, said she is "disappointed" in the performance of hedge funds her firm uses. Zhang, whose CIC manages $200 billion, criticized hedge funds for adopting "herd mentality" of making similar bets.

"Should we pay 'two and twenty' to be treated like this? Maybe we are not making the right decision," she said.

Others are asking the same question. Hedge fund clients yanked $15.1 billion in just the first three months of this year, according to research firm HFR. That marked the largest outflow since 2009.

As they shift away from "active" investing, investors continue to pour money into "passive" strategies. Over the past three years equity ETFs have enjoyed a $405 billion surge of inflows, according to research firm XTF.

These passive strategies are paying off. About 85% of actively-managed large cap equity funds trailed the S&P 500 over the past five years, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Related: George Soros bets big...on gold

Another challenge for hedge funds: many markets tend to move in the same direction these days. That "correlation" between asset classes -- even ones with little in common -- makes it tougher for hedge fund managers to beat the markets.

For instance, in February, there were a couple of weeks when oil and the S&P 500 moved in lockstep 96% of the time. That's abnormal, given that there's been almost no correlation between stock and oil prices in the past decade.

"I've never seen correlation like this," said Emanuel Friedman, CEO of hedge fund EJF Capital. "We've never had this virtuous circle where all six or seven things interact with each other."

There are also regulatory challenges on the horizon for hedge funds. All three remaining U.S. presidential candidates have proposed ending the carried-interest tax loophole, under which hedge fund managers pay a lower tax on their gains than what regular folks pay on income.

Despite lower returns for the industry overall, some hedge fund superstars are still raking in boatloads of cash. The top 25 hedge fund managers earned a combined $13 billion last year, according to Institutional Investor's Alpha. But even that's down from 2013 when they pulled in more than $21 billion.

Related: Political fear is paralyzing investors

So what does the future look like for hedge funds?

It's not clear what fee structure will be deemed the "right" one in today's world. Something that rewards outperformance could make sense.

But lower fees is sure to drive poor performing hedge funds out of the business. "There becomes a point of equilibrium where it's not profitable to run a hedge fund," said Kenneth Tropin, founder of Graham Capital Management.

The challenging political and market environment means the hedge fund industry should "reduce its profile," said Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM, a major sponsor of SALT.

"It might be a good idea to tone it down. I'll leave it at that," he said.