The unemployment rate for African American workers has never been lower — another sign of the strength of the economy.

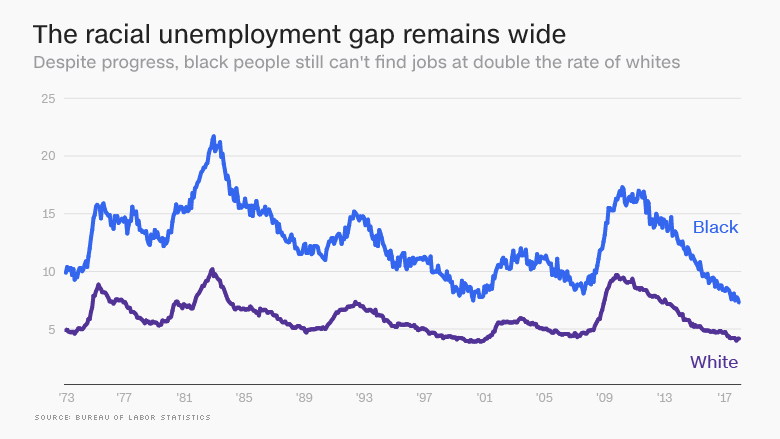

Still, at 6.8%, black unemployment remains well above the rate for white people, at 3.7%. That disparity is deeply rooted and a continuing cause of concern for economists and advocates.

Take Columbia, Missouri. It has long had one of the lowest overall unemployment rates in the country. It's now down to 2.5%, but black unemployment is far higher. In 2016, the last year for which such Census Bureau data is available, African American unemployment locally stood at 8%.

Mike Matthes, the city manager in Columbia, is acutely aware of the problem. African Americans make up 10% of Columbia's population.

"We create the jobs, but never worry about how to get them to the people who need them the most," Matthes said.

To try to narrow the gap, Columbia has worked to connect unemployed individuals with jobs. The city sends cops out on the beat with an app on their phones that can put struggling families into an employer database. Matthes has asked employers expanding in the area, like Aurora Organic Dairy, to make sure its new workforce fits the diversity of the city.

"They didn't blink an eye," Matthes said. An Aurora spokeswoman says the company "will plan to do our best to hire qualified employees who mirror the Columbia community, which would include both gender and racial diversity."

Columbia's projects reflect the larger challenge of making sure people of color, who suffered disproportionately through the Great Recession, share equally in an economy that appears to be picking up steam.

Related: Charlotte's economic success masks deep black-white divide

The racial unemployment gap is an enduring feature of the American labor market, with African Americans averaging about twice the rate of white people. The gap was worst during the late 1980s and has since improved slightly on average, but the white unemployment rate is still only 54% of the black rate. (The average is 4.1%.)

Scholars attribute the disparity to a combination of factors: Hiring discrimination, lower educational attainment, and a higher rate of people with criminal records, who are barred from many occupations.

There has been improvement over the years. In 1990, only 11.3% of African Americans had four-year college degrees, compared to 22% for whites, according to Census data. In 2017, those numbers had risen to 24% and 34.5%.

Still, the racial unemployment gap hasn't receded much. One reason, experts say, is that white and black job applicants are still treated differently. Many studies, which typically test employer reactions to similar resumes with white and black-sounding names, have documented this disparity. A 2017 meta-analysis of the studies found that unequal treatment has remained consistent for the past 25 years.

"I think that the kind of biases that drive discrimination are very resilient and haven't changed a lot," said Northwestern University sociologist Lincoln Quillian, who conducted the meta-analysis, and believes that corporate diversity training hasn't been very effective.

"There was a period of black catching up that occurred in the 1950s and '60s after the civil rights movement," Quillian said. "But after that, there's been a lot more stability than change."

Many employers continue practices that, while not explicitly discriminatory, tend to disadvantage black job-seekers, Quillian said. Allowing executives to hire through their networks, rather than interviewing several applicants for each position, often shut out people of color. Seniority-based systems can be particularly hard on diverse hires, especially when the economy weakens again.

"That tends to work against African Americans who are the last to benefit from strong economic growth," says Valerie Wilson, director of Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy at the Economic Policy Institute. "Once things turn, they're the first considered to be laid off."

Related: The economy is doing great. Here's what could derail it.

The stubborn disparity, Quillian says, underlines the continuing relevance of affirmative action programs in many fields. Other scholars have recommended government-created job programs to make sure people don't fall out of the labor force if the private sector won't hire them.

Some jurisdictions have banned employers from asking up front about an applicant's past criminal convictions, in order to make sure they're not discriminated against.

In addition to the employment gap, African American workers still earn less income and possess only 15% of the median wealth of white families, according to the Federal Reserve.

To Marc Morial, president of the National Urban League, the unemployment rate news was only a small relief.

"When I saw it come down below 7, I partially exhaled," Morial said. "But the fact is that while we're glad people are working, their paychecks don't buy what their paychecks used to buy. And that's got to be a part of any conversation."

Matthes, in Columbia, Missouri, is conscious of that problem as well.

Columbia has one of its lowest unemployment rates ever, but poverty in the city remains high, often for people who already hold down a job. He worries what might happen if the economy tanks again, especially for those on the fringes of the labor market.

To help build incomes, Matthes would favor raising the minimum wage locally, but the state of Missouri, where the minimum wage is $7.85, bars cities from doing so.

"What we've learned very slowly is that our choices create poverty," he said. "You might gain some ground, but it's not permanent."

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the title of the Economic Policy Institute's Valerie Wilson.