|

The 401(k) turns 20

|

|

January 4, 2001: 10:20 a.m. ET

Fastest-growing retirement plan comes of age, but experts see changes ahead

By Staff Writer Jeanne Sahadi

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - Twenty years ago Ronald Reagan was president, the Dow was trading at around 900, and benefits consultant Ted Benna was using a loophole in the U.S. tax code to create one of the first 401(k) plans.

Since then, 401(k) has become a household word, and for good reason. For starters, it has changed the way you save for retirement. The days of the fully funded company pension are over for most people, and the onus is on you to furnish your nest egg.

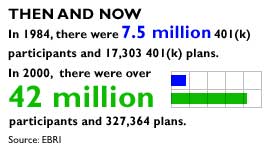

That's exactly what 42 million 401(k) participants are doing. Just ask Baby boomers who got their first AARP mailing. That's exactly what 42 million 401(k) participants are doing. Just ask Baby boomers who got their first AARP mailing.

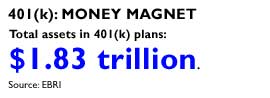

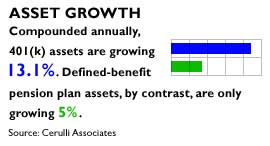

With roughly $1.8 trillion in assets, the 401(k) is the fastest growing savings vehicle, according to research firm Cerulli Associates. Its assets are likely to surpass the $2.1 trillion in all institutional pension plans, whose growth rate is less than half that of the 401(k).

CNNfn.com looks at the 401(k) after 20 years:

Ten steps to a great 401(k)

The basics on rollovers

How to help your heirs

Post your views on the 401(k)

That kind of dollar-power helped fuel the bull market in the 1990s and revolutionized the mutual fund industry, which was quick to market the plans in their early days and now manages more than half of 401(k) assets.

Today, your 401(k) is likely to become the largest asset you own, with the possible exception of your home. And the jobs you choose may depend in part on what kind of 401(k) is offered.

The power of a paragraph

That's an impressive track record for a tax-advantaged savings plan the U.S. government didn't mean to create.

It was a quiet Saturday afternoon back in 1980 when Benna first got the idea for a new plan. He was working on revamping a bank's cash-bonus plan at the time and knew that paragraph (k) of Section 401 in the tax code had gone into effect that year to give legal stature to savings arrangements already in place.

At the time it was common for employees to be given the choice to defer half or all of their non-salaried compensation, often bonuses, into a company's cash-deferred profit-sharing plan. At the time it was common for employees to be given the choice to defer half or all of their non-salaried compensation, often bonuses, into a company's cash-deferred profit-sharing plan.

Section 401(k) essentially gave the definitive go-ahead for that type of tax deferral. But Benna suspected its provisions could be interpreted more broadly. He figured instead of employers putting up money and giving workers the choice to defer, why not let employees defer part of their own salary pre-tax and get an employer match as incentive, particularly for low-paid employees.

"I was stretching the law to suit the design I came up with," Benna said.

IRS gives go-ahead

In 1981, several months after Benna designed his first 401(k) plan for his employer, Johnson Cos., the IRS issued proposed regulations on Section 401(k) that officially sanctioned pre-tax salary reductions.

Click here for EBRI's timeline on the history of the 401(k) plan.

In essence, the IRS made it more straightforward for an employer to provide a salary-reduction savings plan with tax incentives for employees, said Dallas Salisbury, president of the Washington-based Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI).

The pre-tax protection of income was a boon given the high marginal tax rates at the time and the fact that one could contribute more to the plan than to an IRA.

Pension changes pave way for 401(k) growth

But, beyond the tax code, several forces spurred 401(k) growth, not least of which was a sea change in the pension arena, experts said.

Regulatory changes made it more costly and restrictive to run pension plans, especially for smaller firms, said David Wray, president of the Profit-Sharing/401(k) Council of America.

And the government imposed shorter vesting schedules in 1986, Salisbury noted. That meant companies had to increase their pension funding, since more employees would be eligible for payment, even if they didn't stay with the company for more than five to seven years. And the government imposed shorter vesting schedules in 1986, Salisbury noted. That meant companies had to increase their pension funding, since more employees would be eligible for payment, even if they didn't stay with the company for more than five to seven years.

There was also a push for more "portability," where workers could take their retirement money with them. Part of the reason for this was that companies restructured and some older employees lost their jobs. A growing number of people in the work force also started changing jobs more frequently.

Today, the 401(k) has become one of the most advantageous savings tools available, offering benefits for both employer and employee. But there's still room for improvement, experts said.

Savings advocates, for instance, have been pushing for higher contribution levels. Congress is likely consider a bill that would raise the cap on participant contributions to $15,000 a year from $10,500, and would provide a "catch-up" provision for workers 50 and older to save an extra $5,000 a year.

And the 401(k) structure still is evolving to match demand for greater flexibility.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

We need to get the employer out of being the gatekeeper.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Ted Benna

President

401(k) Association |

|

A worker's investment choices, for instance, are likely to move in one of two directions, said Cerulli Associates managing director Peter Starr. They might mirror an employer's institutional pension funds, which are both less costly for participants and are more closely monitored.

Or, he said, they may become more retail-centric, meaning employees would direct all of their 401(k) money into a retail brokerage account, opening up a participant's investment universe.

That sort of change would relieve businesses of some of their fiduciary responsibility, which in Benna's opinion is unworkable. "They're in a no-win situation. They can never have enough funds or the right funds or my favorite funds. And they can be sued," he said.

What's more, for all the talk of participants' control over their investments, all it takes is one merger for a worker to realize she is going to lose access to some fund choice or be told to sell company stock, Benna added. "We need to get the employer out of being the gatekeeper," he argued.

Look for lower costs?

And, given the nearly $2 trillion in 401(k) assets, "Participants should be getting some economy of scale," Benna said.

You may still be paying close-to-retail prices for funds in your plan and high administrative fees on top of that. That may change, Benna said, if firms, especially smaller ones, hire a 401(k) fee-for-service provider that acts as a kind of brokerage offering participants access to a fund network.

The pooling of assets would mean participants could get wholesale prices on many mutual funds, since the provider can buy in bulk for its clients, and fund firms can lower their expenses for participants since they are not providing administrative support for the 401(k) plan.

Benna is a consultant to one such firm, Persumma Financial, which has teamed with mutual fund rating firm Morningstar to offer 401(k) advice and model portfolios for plan participants.

Eventually, this kind of 401(k) could be as long-lasting as a bank account: You may go from job to job but your contributions would continue to be direct-deposited to the same 401(k) account, Benna said.

Indeed, he predicted, "Within 10 years I think the whole market will be restructured in this fashion."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|