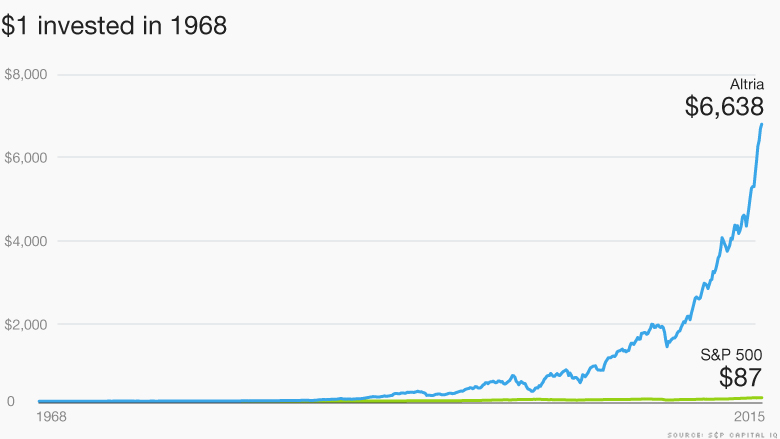

Take a look at this chart. It shows the performance of the most successful company in the world.

One dollar invested in this company in 1968 was worth $6,638 yesterday (including dividends). That's an annual return of 20.6% per year for nearly half a century. No other company comes close to matching its long-term results, according to Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel.

The same dollar invested in the S&P 500 over the same period would be worth $87, or 98% less.

What company is this?

Let's think it through.

It had to have been revolutionary. It had to have been innovative. It must be in an industry that changed the world -- probably the biggest trend of the 20th century. It must have done something no other company could do.

Computers? Satellites? Biotech?

Nope. It's Altria (MO), the cigarette company.

Related: How much money do you need for retirement

Red hot returns: Credit Suisse published a report this week on the performance of every major American industry from 1900 to 2010.

One dollar in the average American industry was worth $38,255 by 2010. That's an annual return of about 10% per year. Some did far better: $1 invested in food companies was worth about $700,000 by 2010. Chemical and electrical equipment companies returned about the same.

Then there's tobacco, which was in a league of its own.

One dollar invested in tobacco stocks in 1900 was worth $6.3 million by 2010. That's 165 times greater than the average industry.

During a century of innovation, progress, excitement, and scientific advancement, no industry did better than cigarettes.

Related: Bankrupt RadioShack wants to reward execs with bonuses

Industry in decline: Most people would look at these numbers and say, "Well, sure. That's what happens when you sell an addictive product."

But what's extraordinary about this story is that the cigarette industry has been in decline for decades.

Cigarettes are, of course, addictive. But smoking rates have been falling for half a century. Half the percentage of U.S. adults smoke today than did in the 1950s. And even though there's been population growth during that period, it hasn't been enough to offsets the decline in smoking rates. Total U.S. cigarette consumption peaked in 1981 at 640 billion cigarettes. By 2007 that dropped 44%, to 360 billion:

By unit sales, tobacco is one of the least successful Americans industries of the last 30 years. Add to it that tobacco advertising has been largely banned for more than a decade, and legal settlements have cost the industry billions. It's amazing tobacco has been able to produce any returns, let alone the highest in American history.

Related: Porsche is planning to eat Tesla's lunch

Foreign sales, pricing power: Part of tobacco stocks' rise is thanks to foreign operations, in countries where smoking is more common and hasn't declined as much as the U.S. But there's more going on here. Altria spun off its international division, Philip Morris International (PM), in 2008. Altria stock is up 289% since then, versus 79% for the S&P 500

Part of it is the ability to raise prices. Tobacco product inflation has increased almost five times faster than overall inflation since 1950. But that, too, doesn't explain everything. A lot of the price increases have been to offset rising tobacco taxes, which in some states make up more than one-third the sales price. (Altria pays far more in excise taxes than it earns in profits.)

There is something about tobacco that leads to extraordinary returns despite a subpar business.

What is it?

It comes down to two factors, both of which are paradoxical and relevant to all investors in all industries.

Related: 1 oil stock I finally bought

Fear, disgust & hatred is good for investors: A lot of investors (understandably) want nothing to do with tobacco companies. Some pension funds are barred from owning them. And then there's the constant threat of litigation, which has hung over the industry for decades. It adds up to millions of otherwise enterprising investors who won't touch tobacco stocks.

Low investor demand keeps tobacco-stock valuations low. Low valuations lead to high dividend yields. And high dividend yields, compounded over decades, add up to massive returns.

The more hated an investment is, the higher future returns are likely to be. The same is true vice versa. This is one of the most difficult investing concepts to come to terms with, but probably the most powerful.

Related: Has Amazon Prime reached a tipping point?

Tobacco companies barely innovate. That keeps them sustainable: Innovation is exciting because it promises something new. New products. New markets. A new future.

But it's expensive. And even if you're great at it -- like Apple (AAPL) is -- you'll probably stumble one day.

The products Apple made just five years ago are utterly irrelevant today. The company has to reinvent itself every few years, continuously coming up with breakthrough products that blow us away. What are the odds it'll keep innovating consistently at the rate it has for another 20, 30, 50 years? Pretty low, I'd say. Even the best players strike out from time to time, and ruthlessly competitive markets show them no mercy. It's rare that a leader sticks around for more than a decade in industries that undergo constant change.

Related: Robert Shiller is buying European stocks

Boring is beautiful: Companies that make the same product today they did 50 years ago are different. They don't innovate, but they don't have to. It's a boring business, but it can be beautiful for shareholders because it keeps the companies chugging along for decades, if not centuries.

The ridiculously large gains from compound interest occur at long holding periods. The key to building wealth isn't necessarily high returns, but mediocre returns sustained for the longest period of time. You typically find that in boring companies that don't innovate, and sell the same products today that they did 50 years ago, and will likely be selling 50 years from now. Food, soap, toothpaste and, yes, cigarettes are good examples.

Morgan Housel owns shares of Altria and Philip Morris International. The Motley Fool recommends and owns shares of Apple. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.