Stolen pay. Sexual harassment. Months without a paycheck. Outrageous fees and expenses that eat away at earnings. And no one to turn to for help.

Models allege that labor abuses like these run rampant in the modeling industry -- leaving many workers feeling more like indentured servants than the glamorous high fashion icons young girls around the world dream of becoming.

While the industry often comes under fire for eating disorders, drug and alcohol abuse and unwanted sexual advances, its problems go far beyond that.

From an analysis of pay stubs and financial statements, interviews with dozens of current and former models, attorneys, labor experts and even a former agency executive, a CNNMoney investigation has found that the fashion world often treats its models in ways that would be unheard of in many other industries. And due to a significant lack of regulation, these abuses can be completely legal.

"It's not an easy industry, you're not going to have a nice lush lifestyle," said Emily Fox, who started out as a model at age 16 and has appeared in Italian Vogue and walked on runways all over the world.

Now 25 years old and still working in the industry, Fox says that most years she earns less than $20,000 before taxes. "You're going to really struggle and you'll be really poor."

Of course, as in any creative and competitive industry, not everyone is going to make it. But models argue that industry practices are a big part of what keeps them from finding success -- especially financially.

One model claims she was forced to rely on her father, a blue collar worker in Ohio, to pay for groceries -- even after gracing the pages of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue. Another, from Britain, resorted to working illegally as a bartender at an Irish pub in New York City to make ends meet. An 18-year-old who entered the business last summer and has already appeared on a number of European runways claims she has yet to receive a paycheck. And a Jamaican model ended up receiving only a few thousand dollars over three years of work in New York -- despite being promised a $75,000 annual salary on official visa documents. (Her agency disputed any wrongdoing, calling the salary a "guesstimate.")

Some situations are downright dangerous. In Florida, a number of young women were so desperate for modeling work that they fell victim to a fake business that allegedly drugged them and used them to create pornographic films.

Welcome to the dark side of the modeling industry -- the one that goes beyond the glossy magazine covers, designer labels and world famous runway shows.

"When you're a supermodel like Giselle or Christy Turlington you're treated like royalty, but 99% of models are treated like garbage," said Carolyn Kramer, a former agency executive who compared the industry's labor abuses to those faced by young factory workers at the turn of the century.

A cutthroat industry

For decades this world has operated in the shadows -- blatantly taking advantage of its young, mainly female workforce. Many models are thousands of miles away from their families, while foreign models often speak little English and are trapped in immigration programs that make them that much more vulnerable. Others aren't in immigration programs at all, but are instead encouraged by agencies to come to the United States illegally.

In many cases, models say it's the agency (or management company, as some call themselves) that takes advantage of them. While they say the designers and brands they pose for can also be part of the problem, models interviewed by CNNMoney were more concerned about agency practices and didn't single out clients.

Of course, some agencies do indeed act as fierce protectors of their models. But the lack of regulation (or a labor union like actors, classical musicians and athletes have) makes it easy for bad apple agencies and fashion houses to thrive, allowing them to treat workers as nothing more than a source of profits.

While the fashion world's most famous faces rake in millions, many aspiring and working models earn unlivable pay and end up indebted to their agencies -- as a perfect storm of 20% commissions and expenses drastically reduce earnings.

The few modeling companies that responded to CNNMoney's inquiries, however, were adamant that the financial issues models complain about are unavoidable in a cutthroat and competitive industry -- that it's just the economic reality that most of the money goes to a small fraction of models.

"Like in any industry, many models are not successful [due] to various issues, such as a lack of commitment, physical problems, or personality flaws," said MC2, a modeling company, which said that it generally discontinues representing any New York-based model that makes less than $150,000 annually. "Just as not every actor or musician will find commercial success, not every model will be successful."

'A toxic power dynamic'

The industry's labor issues often stem from the fact that even though models say agencies control much of their lives (down to their eating habits and the pay they receive), they typically aren't considered employees.

Clients don't typically claim them as employees either. Instead, models are left as contract workers in an industry with little oversight -- making it very difficult for them to challenge everything from wage theft to sexual harassment.

"There is this culture that comes from the agency that you are disposable and you are so lucky to be here," said former model Meredith Hattam. "It's a toxic power dynamic and it starts from the top."

A number of the industry's top players are currently battling a lawsuit that challenges these very labor practices. The suit, proposed as a class action, alleges that the firms have unfairly profited off their models by charging exorbitant fees and expenses, incorrectly classifying them as independent contractors and withholding wages, among other allegations.

In response, the named modeling companies have denied any wrongdoing in court, claiming that allegations of stolen pay and unfair profits are baseless. They have also argued that it would be incorrect to consider models employees because they work sporadic hours and for all different clients.

Email us tips and your own stories at CNNMoney Investigates

MC2, for example, told CNNMoney the idea that a management company has complete control of a model's career is untrue, countering that "each model is free to refuse any booking they choose."

An attorney for Click, another modeling company named in the lawsuit, wrote in court filings that it's important to note that models technically hire a management company -- and not the other way around. He also said it doesn't make sense to evoke minimum wage and overtime laws for models who can bill hundreds or even thousands of dollars a day.

And Katia Sherman, the president and co-founder of Major Model Management (which is also named in the lawsuit), said that many companies like hers are mom-and-pop operations that wouldn't be able to survive if they were required to provide employee benefits to their models. She also said that just because her models aren't her employees doesn't mean she's not looking out for their best interests. And without these agencies to support aspiring models, it would be even harder for young people to break into the industry.

"My models are my children," said Sherman. "I care about all of them. This business is not all about money, but about people."

Low pay, high expenses

Models interviewed by CNNMoney acknowledged that some agencies do negotiate fair compensation for shoots and chase down deadbeat clients. But many said that when they expected this kind of parental support from their agents they were instead thrown to the wolves.

Many get their start in their early teens, and come to the big fashion meccas like New York and Miami on their own. Desperate to please their agents and find work, they're willing to accept pretty terrible labor conditions.

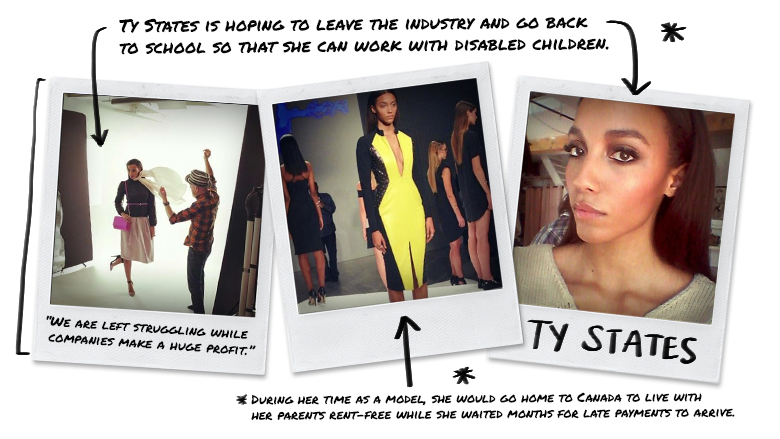

"We are left struggling while companies make a huge profit," said Ty States, 24, who is hoping to leave the industry and go back to school so she can work with disabled children. During her time as a model, she would go home to Canada to live with her parents rent-free while she waited months for late payments to arrive.

Part of the problem: the industry's more lucrative jobs -- like high-profile advertising campaigns -- are very competitive and typically go to those who have "paid their dues."

Meanwhile, high-profile gigs often pay very little, instead paying in prestige. CNNMoney saw countless examples of hours-long work -- from editorial shoots at fashion magazines to fancy runway shows -- that paid models $500 or less before commissions, taxes and expenses.

Others pay nothing more than free clothes, (though some say this practice is declining). That's because agencies don't classify models as employees, and as a result they avoid minimum wage laws (though several lawsuits are currently challenging this classification). And the countless hours spent at castings, test shoots and go-sees (meetings with agents or designers) usually result in no compensation at all.

For the long hours she spent at runway shows and photo shoots, Fox has been paid with everything from a bizarre dress that she has never worn to a pair of beige bellbottoms. Others say a coveted shoot for Vogue has earned them only around $200 (though the magazine has been known to help launch careers). Vogue declined on-the-record comment for this story.

And no matter what the job is, agencies -- and clients -- can take months to pay anything at all, models say. To afford their bills, some models resort to taking cash advances from their agency, which further reduce their pay with fees of around 5%.

"A lot of us don't have rich parents or somebody to take care of us," said male model Alex Shanklin, who is part of the proposed class action suit. "When you work you would expect to at least get a paycheck in a timely manner, but that never really seemed to be the case. It was almost a hide and go seek with the check."

When a paycheck does arrive, it's often a fraction of what the client actually paid the agency. In addition to big commissions, earnings can be devoured by other deductions as models are billed for expenses ranging from walking lessons and dermatology visits to overpriced accommodations.

Marcelle Almonte says she was one of nine models who was charged as much as $1,850 a month to stay in a two-bedroom "model apartment" in Miami, according to the same lawsuit. With a market rate of around $3,000 a month for the entire apartment (as Almonte alleges in the suit), this would mean the agency could have taken in more than $10,000 a month in profits.

Want updates on this and other investigations? Sign up here

The management company, MC2, disputed this in a statement, claiming that it actually lost money on the apartment because of vacancies and models who didn't earn enough to cover their payments.

Meanwhile another member of the lawsuit, Louisa Raske, who worked for clients like L'Oreal, says her agencies have billed her for everything from messenger service and website promotion to client Christmas gifts and flowers given to her on her own birthday.

Expenses like these can leave workers in the red for months, years or even their entire careers.

Fox, for example, says she's owed her agency at least $5,000 at a time, while Lisa Yanowitz (formerly Davies) says that she spent her 14-year modeling career bouncing in and out of debt. She has since left the industry to become a nurse, which she says is a much more stable job.

"Most models never manage to get out of debt. Most models never make any money," said prominent model and actress Milla Jovovich in a recent letter urging lawmakers to take action. In her letter, Jovovich detailed the "outrageous" expenses and labor abuses in the industry, even recalling how, as a teenager, she worked a 24-hour day with no pay.

Models acknowledge that the contracts they sign allow for these deductions, but they say that they are typically expected to pay with little proof or explanation of the charges.

And they worry that if they challenge these expenses, they will be blacklisted from the future jobs they so desperately need.

"A lot of times if you get too concerned or you get too involved, you can feel the agency not liking that," said Addison Gill, a Canadian model who has worked for clients including Calvin Klein, Louis Vuitton and Valentino. "They prefer to deal with girls that aren't questioning them."

This is making it?

Even those who "make it"-- often earning around the six-figure mark but far from the millions of dollars raked in by the industry's most famous -- still claim they face a complete lack of transparency.

They complain that their agencies steal money that is rightfully theirs and continue to tack on excessive fees and expenses that can take up more than half of their pay. Almonte, for example, has a statement showing that 70% of a $1,000 paycheck from a lingerie and swimwear company was eaten up by vague expenses charged by her agency (not even including commissions or taxes).

Others say that agencies and brands profit off of their images without their knowledge -- and without paying them.

Retired model Carina Vretman, for example, says she has had to chase down payments after seeing her face on everything from boxes of hair dye to London billboards. She says she would have lost out on tens of thousands of dollars had she not fought back.

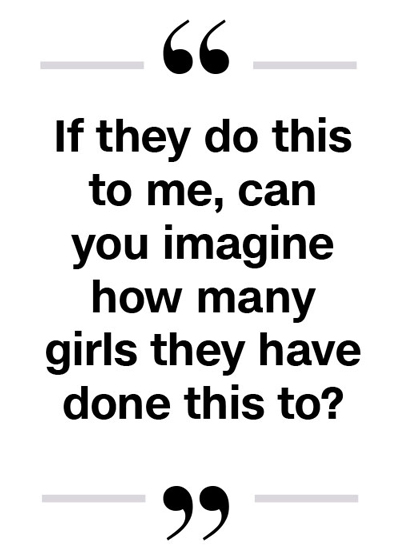

"Why should the agencies take my money?" said Vretman, who is also part of the proposed class-action lawsuit. "They are supposed to represent me, they are supposed to be looking out for me. If they do this to me, can you imagine how many girls they have done this to?"

Lawyers for her agency, Wilhelmina, did not respond to requests for comment but have stated in court documents that the claims against the management company are "meritless."

Raske, a co-plaintiff in the same lawsuit, even alleges that someone at her agency forged her signature on a tax form in order to receive payments from a client without Raske's knowledge.

The company, Next Model Management, did not respond to a request for comment, though Next has denied any wrongdoing in court.

"It can be an ugly industry -- the ugly industry of modeling," said Carlos Carvajal, a New York attorney, who is not involved in the current suit but has represented both models and their agencies.

Abuses remain unchecked

With little oversight of the industry, critics say abusive agencies and their clients remain unchecked.

In contrast, consider another class of creative workers: actors. Whether they're on a commercial set or a Broadway stage, actors benefit from a laundry list of union protections, including mandatory breaks and overtime, minimum salary requirements and prompt payments. They also typically pay their agents commissions of only 10% because of union rules.

While actors have been unionized for decades, attempts by models have been crushed by agencies, said former model Sara Ziff, who was the face of brands like Tommy Hilfiger and Stella McCartney before founding the Model Alliance, a labor advocacy group.

It's already very difficult for independent contractors to create a union since they lack many basic legal protections and rights, she said. Then there's the fear that they will be blacklisted if they join labor efforts.

As a result, Ziff argues government regulation is sorely needed.

With no federal regulation of the industry, states have taken a piecemeal approach. Only some have laws requiring modeling agencies to be licensed. And while a recent law in New York State, (where models often spend the bulk of their career) significantly strengthened protections for underage models, critics say there are still few protections for those 18 and older.

Meanwhile in California, a lawmaker has introduced legislation that advocates say would provide the strongest labor protections in the industry so far. The bill would require models to be treated as employees, among a variety of other labor, health and safety-related regulations.

It is expected to be voted on by the legislature later this year, but the industry is already fighting hard against it with a state trade group of talent agencies calling it "misguided and unnecessary."

And even if this landmark bill becomes law, it would only help workers in the state. So without a much larger overhaul of the way the industry operates, many say models will remain in the same vulnerable situations they've been in for decades.

"It's like throwing fish into a piranha tank," said longtime model Lorelei Shellist, who has appeared in magazines like Vogue and Marie Claire. "They're going to get devoured."