The American Dream remains alive for one particular group of folks.

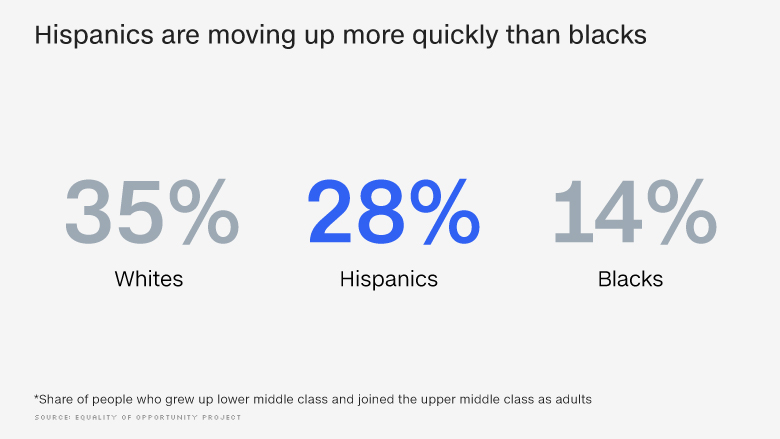

Hispanic-Americans are doing much better than their parents when it comes to income mobility. They are climbing up the economic ladder just slightly slower than their white peers, but much faster than blacks, according to a study by Stanford, Harvard and Census Bureau researchers.

For instance, among those who grew up lower middle class, 28% of Hispanics made it to the upper middle class or higher, compared to 35% of whites and only 14% of blacks. And 14% of middle class Hispanic kids made it to the top of the income scale, compared to 19% of whites and 7% of blacks.

Hispanics also were more likely to escape poverty. Some 45% of Hispanics who grew up in the lowest income quintile made it to the middle class or even higher, compared to 46% of whites and 25% of blacks.

The report, the latest work from economics professors Raj Chetty of Stanford and Nathaniel Hendren of Harvard, looked at the earnings of those born in the late 1970s and early 1980s. They then compared these 30-somethings' earnings with their parents' income from the mid-1990s to 2000. The study excluded children or parents who were undocumented immigrants.

The research comes at a time when Hispanics are facing a backlash in America. President Donald Trump has repeatedly disparaged Latino immigrants -- particularly Mexicans -- calling them criminals and a drain on society.

"We are in a critical time period where Latinos are navigating their mobility in a social and political context that's extremely hostile," said Jody Agius Vallejo, associate director at the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration at the University of Southern California.

The study did not delve into why the Hispanic children in the study were experiencing greater mobility than their black peers. Sociologists, however, have looked at the trend, and their research generally backs up the study's findings. There are some reasons for why this is happening.

It's likely many of the parents in the study were legal immigrants who came to the United States after the gates reopened in 1965, said Van Tran, assistant professor of sociology at Columbia University. These folks generally had less education and worked in lower-paying jobs. However, their children -- particularly ones from Mexican, Salvadoran, Guatemalan and Honduran families -- often have more years of schooling. This allows them to secure higher earning positions.

Related: Latinos key to U.S. economic growth, study finds

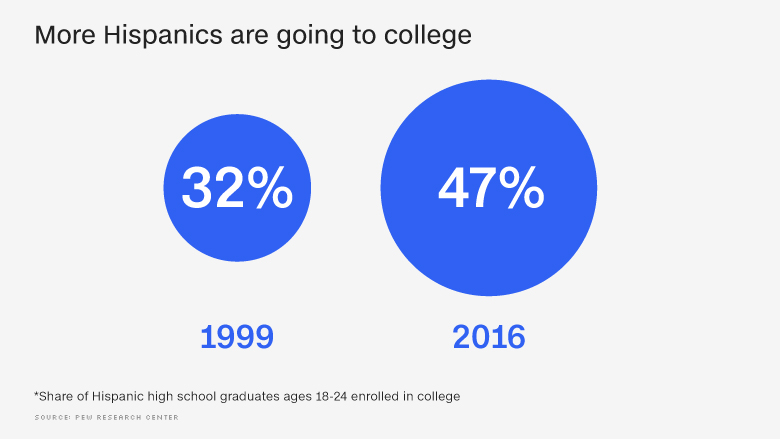

Nearly half of Hispanic high school graduates, ages 18 to 24, were in college in 2016, up from just under a third in 1999, according to the Pew Research Center. The share of college enrollees among their white, black and Asian counterparts increased more modestly.

Also, second-generation Americans often inherit a strong work ethic from their parents.

"The children of immigrants have long been shown to be more driven, motivated and have exceptional outcomes," Tran said. "They are in a good position to maintain those gains as they enter middle age in the next decade."

Hispanics are also building wealth across the generations.

Related: Banks are walking away from low-income homebuyers

The children and grandchildren of Mexican-American immigrants are slightly less likely to be raised in poverty than blacks, Vallejo said, citing a paper she coauthored in 2015 on Mexican-American mobility and wealth. Also, they are more likely to own homes and accumulate more wealth than blacks, though not as much as whites. This is particularly true for families of legal immigrants since they and their children have greater access to better schools and more secure employment.

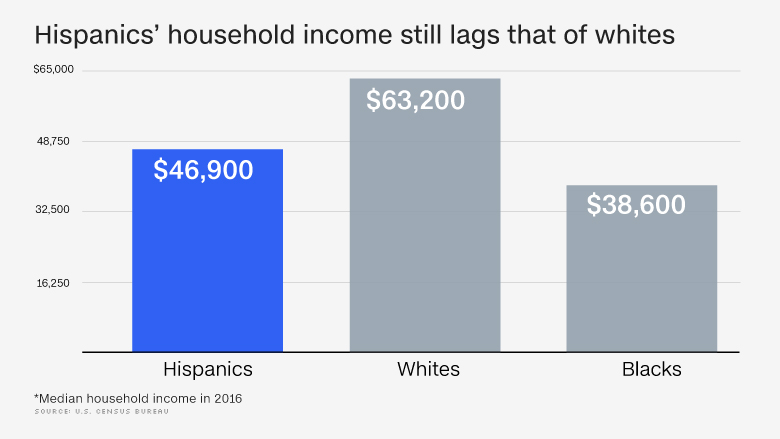

Hispanics, however, still face barriers to advancement. Some experts question the paper's assertion that Hispanics are on a path to potentially close much of the income gap with whites, in part because the upward mobility of the third generation tends to slow. In 2016, the median household income was $63,200 for whites, $46,900 for Hispanics and $38,600 for blacks, according to the study, citing Census data.

While more Hispanics are entering college, many are dropping out before they graduate, said Eric Rodriguez, vice president of policy and advocacy at UnidosUS, a research and advocacy groups serving the Hispanic community. They find they are not academically prepared for higher education, have a harder time leaving their homes and are often working to support their families -- all of which makes it more difficult to succeed in college.

This is leaving them with thousands of dollars in student loan debt. But without the degree needed to land a good-paying job. The debt makes it harder for them to increase their income, buy a home, save for retirement and take care of their families.

"Latinos are not doing fine," Rodriguez said. "The system needs interventions that will promote success and greater mobility."

He would like to see more affordable housing options, as well as measures to assist low-income folks with purchase or rental costs. The federal government should invest more in helping low-income students prepare for and pay for college.

Also, Hispanics still face a glass ceiling in corporate America, said Vallejo, who has researched the Latino middle class and economic elite. She has found that members of these groups still encounter discrimination.

"They are assumed to be undocumented or the help or are viewed as criminals in their every day lives," she said.