SALEM, Ore. (CNN/Money) – On a recent evening I bought into a limited partnership, flipped a bed and breakfast for a quick profit, tripled my money on "OK4U" pharmaceutical stock. I also got downsized from my teaching job, bought a duplex and had a baby.

After all of that, I managed to get out of the proverbial rat race. But my financial skills, or luck, were no match for Mitch.

"I have waited all of my life for this," said a euphoric Mitch when he realized that his investments in a handful of companies had finally paid off.

In real life, we're told to make the most of the cards we're dealt.

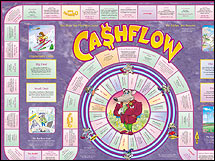

In "Rich Dad, Poor Dad" author Robert Kiyosaki's board game, Cashflow, the goal is to make the most of the financial scenario you're given.

The game, which might be described as Monopoly meets Dungeons & Dragons, has become a cult favorite around the world. To date, about 350,000 copies of the $195 game have sold, and more than 300 Cashflow clubs now meet to play the game and apply its lessons to real life.

The "Lazy Pig Millionaires Club" in Paris describes itself as an ambitious and dynamic group of people who, despite their club name, wish to improve all areas of their lives. The Achievers club in Harare, Zimbabwe, wants to make "massive passive income." In Toronto, the game's enthusiasts will meet later this month to learn more about the game and attempt to make the Guinness Book of World Records.

"We have it all in this group," said Ed Patisso, co-founder of a Cashflow club in New York, which meets every week at the Sony Plaza in Midtown. "Attorneys, accountants, corporate leaders, mailmen, police officers and music artists."

Teach them something

"I think of myself as the guy who didn't do well in school but knew how to make money," said Kiyosaki, who invented the game before writing his best-selling account of the contrasts between his highly educated "poor dad" and his best friend's bootstrapping "rich dad."

|

|

| A game like life |

While Kiyosaki's unconventional philosophy has struck a chord with fans, it has also been the source of criticism among those who advocate "poor dad" strategies -- such as investing in mutual funds and managing financial risk. (Read "Kiyosaki Mania.")

I was never a critic, because that would have required actually reading the book. I will admit, though, that my eyes did roll every time someone told me about how the book changed their lives. And recently, that was becoming a pretty regular occurrence.

So I decided to play the game. Besides, slurping coffee over a board game for a few hours would be a welcome break from the, er, rat race.

Having found each other on Kiyosaki's site, six of us met at a local café to play a hybrid version of Cashflow 101 for beginners, and the more advanced 202. We introduced ourselves, then randomly chose our professions for the evening.

I drew the elementary teacher card, which meant that I'd initially earn $3,300 on pay day and pay about $2,200 in expenses. Vicki, the club's organizer, would be a police officer, while her 11-year-old niece, Charleen, happily accepted the janitor profile.

Mitch, a registered nurse in real life, was to be a secretary. Barbara, an office manager by day, drew the dreaded airline pilot card. Monte, an engineer, would be living the life of a truck driver.

We started the game in the "Rat Race," collecting income from our jobs, paying bills, hoping to not get downsized and trying to buy investments that would eventually pay enough regular income, or passive income, for us to say goodbye to our day jobs and move on to the game's "Fast Track."

One of the key lessons, said Kiyosaki, is that cash alone does not get you out of the Rat Race. That's why Barbara was not thrilled about her role as an airline pilot. She would need several times more passive income than the rest of us to quit her job and still pay her expenses.

Another lesson, according to Kiyosaki, is that low-risk, low-reward investments, like CDs, won't help you get out of the Rat Race. He believes that rental property, franchises and other business ventures are a better bet.

"The people who win are usually the ones who take risks," said Vicki. "Kids often do better than the adults because they're not as fearful."

Luck has a lot to do with who wins and who loses. Charleen, for one, spent much of the game having babies and getting downsized. Mitch won because he drew the right "opportunity cards."

"It's just a game," said Kiyosaki when I asked him about whether Cashflow teaches anything about managing investment risk or analyzing stock.

The point, he said, is to get people excited about investing money instead of just spending it.

Driving home that night, I did feel richer, more optimistic and more open-minded -- and extremely wired from all that coffee. I read Kiyosaki's book cover to cover.

I can't say I'll be giving up my day job or my mutual funds or my emergency cash any time soon, if ever. But the next time someone tells me that Kiyosaki got them excited about investing, I might nod my head instead of rolling my eyes.

When my husband comes to me with his latest big idea, I might even try to think like a rich dad instead of a devil's advocate.

|