|

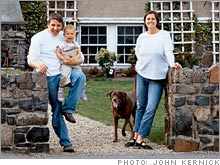

| Richard and Day Newburg, daughter Maia and Lincoln the chocolate Lab. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NEW YORK (MONEY Magazine) - "Are you out of your mind?" Day Newburg cried to her husband when they first drove up to the majestic three-story shingled house overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

Richard had just suggested buying the 100-year-old summer home in the exclusive Marblehead Neck section on the North Shore of Massachusetts.

Price tag: $1.7 million.

The Newburgs, you see, are not the kind of people who usually own million-dollar houses. Day, 34, gave up her job as a medical technician two years ago when their daughter Maia was born. Richard, 36, runs a real estate appraisal business, earning $130,000 or so a year.

That's a comfortable income, sure -- but Marblehead Neck? Where tycoons like Peter Lynch live in walled-in compounds? "I thought he was kidding," says Day.

But she also knew the kind of man she'd married -- a real estate entrepreneur and self-described "old house nerd" who insisted they tour the 14-room home for fun.

What they saw charmed them: flawless wood floors, five fireplaces, original skeleton keys dangling from door locks. "The house has a kind, gentle soul," says Richard. "I just loved it."

What really sold them, however, were the spectacular views.

Perched at the mouth of Marblehead Harbor, the house was drenched in the morning sunrise over Salem Sound and, at day's end, a blood-red sunset over historic Old Town.

As Day stood on the back porch gazing at the sea and the nearby lighthouse, she fell deeply in love too. "People here talk about whether they would rather live on the harbor side or the ocean side," she says. "This house has both."

It was the kind of place, they remarked, that would make a perfect New England bed and breakfast -- and suddenly a light went off in their heads. "Opening a B&B is the way we thought we could afford to buy the house," says Richard.

The odyssey begins

So began Mr. and Mrs. Newburg's wrenching odyssey to acquire and renovate their magnificent new home -- a saga built on complex financial deals, plenty of sweat equity and boundless optimism, none of which were quite enough to prevent the Newburgs from running out of cash and energy before the renovations could be completed.

Eighteen months later, the B&B has yet to open and the couple can barely cover their monthly bills. Exhausted from working on the house nonstop, nerves frayed, Richard and Day bicker over how the B&B should be decorated and sometimes wonder if Day's initial reaction wasn't the right one.

The key questions: How much longer can they afford to go on? Is it time to give up and just dump the house for a tidy profit?

"Hey, Rich, do you have any money?" Day's voice drifts up to the third floor, where Richard is prowling around the two bare-walled, still undecorated suites of the B&B they plan to call One Kimball at Marblehead Light. He rummages through his pockets. Day is just looking for a few bucks to pay the guy delivering meatball sandwiches for lunch. But, inadvertently, she has posed a trenchant question.

No one will go hungry, of course, but the answer is basically no -- Rich has very little money.

Of the roughly $7,500 that he brings home each month, nearly 60 percent goes to paying their mortgage and property taxes. Add college loans, utilities, insurance, food, clothes for Maia and medication for Lincoln, their beloved chocolate Labrador (diagnosed with cancer but still hanging in there), and the family barely breaks even each month.

Nothing is left for their small retirement account, disability insurance for Richard or a college fund for Maia.

Juggling the finances

Such is the seductive appeal of ocean sunsets -- and of living in an aristocrat's estate that once was surely filled with flappers, linen suits and hot jazz on breezy summer nights. That's pretty heady stuff for a couple of kids from Marblehead High who were reunited through mutual friends in their twenties and got married three years ago.

"We kept saying, 'It's going to be really hard,'" Richard recalls. But he had done well with various local real estate investments with this brother Stephen, and Day trusts him completely. "He always comes up with creative ways to make things work."

Only the most creative and adventurous mind, in fact, could have devised the Rube Goldberg contraption of a financial plan that allowed Richard to buy and renovate this house.

First he negotiated the price down to $1.27 million, nearly half a million less than the asking price. Then, to come up with the down payment and initial cash for renovations, he used savings of $63,350, took out a second $200,000 mortgage on the home they owned in Salem and borrowed $110,000 from his family -- a short-term loan that he would repay as soon as he sold the Salem house.

The Newburgs also launched a draconian cost-cutting campaign, trading their Volvo station wagon for a Honda Element and canceling premium cable, spring-water delivery and even Richard's life insurance policy (since reinstated).

But belt tightening alone wouldn't enable them to make the payments on a conventional 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. So Richard gambled on an adjustable-rate loan that, at just 3.4 percent for the first year, cost nearly $1,100 per month less.

The downside: Their monthly payments could skyrocket if, as widely anticipated, interest rates rise (their rate, adjusted annually, has already climbed to 4.4 percent, boosting the monthly payment by $247).

Once the deal was done, Richard found himself in a catch-22 situation. The family could not move into their new home until it was winterized. But he couldn't afford the necessary renovations until he sold the old place in Salem.

As February and March came and went with no buyers, Richard became increasingly anxious. He'd wake up in the middle of the night worrying about everything from the real estate bubble bursting to another terrorist attack.

"Our life was like a speeding bullet train; any little thing could knock it off the tracks," he says. "Everybody we knew thought -- and still thinks -- we're crazy."

Work begins..and then keeps going...

In April 2004, Richard finally sold the Salem house. Using his $90,000 profit, plus $50,000 borrowed from his appraisal business and another $50,000 from a second mortgage on One Kimball, he got down to work on his new home.

Doing a lot of the work himself to save money, Richard and his contractors poured new concrete in the basement, insulated the house, installed central heating and cooling, rewired the electrical system, upgraded the plumbing and built a kitchen stairway to give B&B guests their own private entryway.

With their new home a construction zone, Richard and Day stayed with his mother. For two months they slept in single beds in the small bedroom he grew up in, along with one-year-old Maia and cancer-stricken Lincoln. Richard worked at his appraisal business by day, then at the Marblehead house by night.

Last July the family moved in. Day and Richard could watch the sun rise over the water from their bedroom window, and enjoy the Fourth of July fireworks lighting the sky over Marblehead's fishing village from the back porch. Their dream seemed to be coming true. But Richard knew that until the B&B was up and running, they were not out of the woods.

"Day always says, 'I trust you if you think we can do this,'" says Richard. "My family says that too. But that makes me nervous. Because if it doesn't work out, I know who they're going to blame."

Naively, Day admits, she hoped they could open the B&B last summer. Richard thought it might take until winter. But when their $200,000 renovation budget dried up at the end of the summer, they were too exhausted to tackle the work they planned to do themselves. By then Maia had become a rambunctious toddler who demanded lots of attention. So jobs like painting the interior dragged on for months -- and tensions flared.

"I'd wake up at seven on Saturday morning to start painting, and Day would say, 'I guess it's another day of me chasing the baby,' " Richard says. They also argued about how to decorate the B&B. "What he's good at is real estate," says Day, "but I don't think he knows how much 12 yards of fabric costs."

Increasingly concerned about money, Richard and Day decided to meet with a financial planner. Day had suggested this long ago, but Richard had been avoiding it like a guy with a toothache who won't visit the dentist: "I'm afraid he'll tell me I'm going down the tubes," he says.

Bob Ryan of Resolute Financial in Newburyport, Mass. sat down with the Newburgs in April and pored over the numbers. Sure enough, Ryan was alarmed by their poor cash flow and the fact that nearly all of their assets are in real estate. If interest rates rise by three-quarters of a percentage point each year, he says, they'll be paying over $5,000 a month in interest alone by 2008.

"Richard has a perfect storm of a problem," says Ryan. "If rates go up, his appraisal business could go down, the value of all his properties go down, and his mortgage payments go up."

|