Selling clean machines

Entrepreneur David Oreck explains how he built a small distribution firm into a vacuum cleaner empire. His secret? Innovating more persistently than his competitors.

|

| Oreck's new models - such as the XL Ultra - cost more than the competition's but come backed by strong customer service. |

|

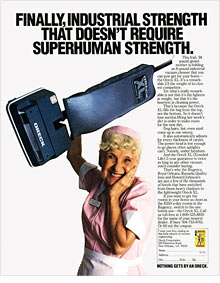

| Early ads targeting hotel managers highlighted Oreck's eight-pound vacuums. |

(Fortune Small Business) -- When the U.S. entered World War II, David Oreck quit college to enlist in the Army Air Corps. At war's end, the idea of returning to class - and Minnesota, his home state - seemed too tame for a young man used to flying B-29 bombers. Instead, he took the first job he was offered: salesman at a Manhattan appliance distributorship.

Sixty years later he is still selling appliances - about $350 million worth each year. The Oreck Corp., which he founded in 1963, has grown to 1,500 employees and 100 company-owned stores - and is profitable. Although Oreck, 84, handed off the CEO title to his son Tom in 1999, he visits the office almost daily to suggest new products and marketing strategies. FSB caught up with him at the original Oreck store near New Orleans, and he told us, in the account that follows, how he became a household name.

When I left the military, the only thing I had ever sold was Saturday Evening Post subscriptions. But in 1946, I managed to land a job in Manhattan with Bruno-New York, then one of the nation's largest appliance distributors. Bruno carried the first automatic washing machine and the first TV sets and was RCA's largest wholesale distributor. The firm also handled Whirlpool (WHR, Fortune 500), which manufactured its own line of vacuums.

After 17 years of working for Bruno, I became head of sales. Then I turned 40 and decided it was time to be my own boss. I was selling the heck out of Whirlpool's vacuums in New York City - at one point our distributorship represented about 30% of the company's vacuum sales. When the president of Whirlpool heard I was looking for the right opportunity, he asked me to be his sole vacuum distributor nationwide, allowing me to run my own independent business.

Of course I accepted, but I quickly realized that the reason Manhattan made up such a big percentage of Whirlpool's sales was that the vacuums weren't doing well anywhere else. It made models for Sears (SHLD, Fortune 500) Roebuck to sell under the Sears label, and didn't want to upset their biggest customer by competing with it. So I suggested that we sell vacuums under another name, and I used my connections with RCA to get permission to brand them as RCA-Whirlpool.

In those days upright vacuums weighed about 20 pounds and filled from the bottom, which meant they had to lift up yesterday's dirt to make room for today's. To combat the problem, Whirlpool tried developing a lighter model that filled from the top.

The idea seemed as if it could be a real competitive advantage. But the pipe clogged and sent dirt everywhere except into the bag. I met with the engineers at Whirlpool, brainstorming ways to fix it. We came up with a solution that worked so well that today my vacuums work on the same principle: The pipe enters the bag via the handle, which is hollow. The result: a vacuum that weighed eight pounds! Whirlpool started manufacturing them just for me.

It didn't take long for competitiors such as Hoover to start swinging. Its salespeople told customers that a lightweight vacuum such as ours would be flimsy - poorly made. Instead of pursuing consumers, I decided to target hotels, which clean miles of carpet a day. That would prove my product was powerful enough for the home.

Around the same time, I heard that a Chicago company, Ozite, had recently invented indoor-outdoor carpet. It had a very low pile and was glued to the floor, which made it durable but nearly impossible to clean. I decided to fly out there unannounced, where I introduced myself to the receptionist. Her desk sat on dirty Ozite carpet.

I had two vacuums under my arm and asked if I could see the president. "Do you have an appointment?" she asked. "If not, you can't see him." I then asked to see the sales manager, and when she refused again, I asked in desperation, "Can I show you my vacuum cleaner?" At that point she just wanted me gone, so she told me to plug it in.

It took me less than a minute to clean the carpet. She wasted no time in paging the president and sales manager! I showed them the clean carpet, and they were astounded - they had been struggling to figure out how to clean it. They asked if I would create a pamphlet to send to dealers. (Today our company does about half its business by mail, online, and phone.)

After a year or so of selling to hotels, I wasn't making enough money to support my family. I had been trying - to no avail - to get my vacuums into Marshall Field's to tap into the consumer market. That's when RCA called and asked if I wanted its New Orleans operation - running an independent distributorship selling radios, records, and TV sets.

At first I thought, "I'm a big shot in New York trying to build my own company. Why would I go anywhere else?" I went to the airport in my heavy coat to catch a flight.

After three or four days of looking at the situation and enjoying the gorgeous weather, it was obvious that I couldn't do any worse than the guy I was replacing - he had the worst performance of any RCA distributorship in the country. I called my wife and kids and said we were moving. My brother managed my vacuum startup in New York City for two years until I could move it to New Orleans.

So then I was dealing with two businesses at once - distributing RCA products while growing my vacuum venture - when I ran into a snag in 1963. The president of Sears Roebuck, who sat on the board of directors at Whirlpool, decided my mail-order venture was cutting into Sears's business. He persuaded Whirlpool to stop making vacuums for me. It was a huge disappointment - the previous year I had sold about 100,000 RCA-Whirlpool vacuums. But at least I could finally put my own name on the product! I quit distributing RCA products and launched the Oreck Corp.

After I found a manufacturer in Germany that could build my product, I started to think seriously about marketing. We did well with mail order, but our customers wanted to try before buying. Selling through distributors wasn't an option - there wasn't a way to guarantee uniform-quality customer service. In the early 1970s I opened the store we're sitting in now.

Today we do about half our business through 500 Oreck stores, 80% of which are franchises. We opened the stores to shorten the lines of communication between us and customers, observing what they liked and didn't like. I call myself a "screwdriver engineer." I have no formal training, but I consider myself mechanically minded. I'm always trying to come up with ways to fix things. For example, when folks complained about not being able to clean well in corners, I thought up "whiskers" on the ends of the roller brushes that could reach into tight spots, loosening dirt.

If we couldn't fix your broken Oreck vacuum while you waited, we'd send you home with a loaner. But we also serviced other brands, and if we couldn't fix them on the spot, we'd give out a loaner - an Oreck loaner. And often customers liked it so much that they didn't want the old one back!

That's when our brand really started to stand for something. I wanted happy customers, and if that meant giving them their money back, so be it. Folks can still try our vacuum for a month, and if they don't like it, we'll take it back. We don't sell the cheapest product on the market - you pay $300 for a basic upright, compared with the $200 you'd spend on a Eureka - but price is only one component of value. Customers want value. If they have confidence in your brand, they'll pay a premium for it.

It's important to me to know I'm doing the right thing not only for customers, but for employees also. When Hurricane Katrina hit our factory in Long Beach, Miss., we brought in temporary housing, doctors, and nurses. Nobody missed a paycheck.

Unfortunately we weren't able to rebuild the facility - the location was vulnerable to another catastrophic storm. In 2006 we moved to a new site in Cookville, Tenn. It was an unhappy decision, but it was the most prudent one.

I'm no longer a company officer, but Oreck is still my hobby, my work, my everything. Besides, I like to vacuum! I use my own product almost every day. And you know, I still notice little things that could be changed or improved. ![]()

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More