Cattle auctions and Imus: A rural TV empire

A former farmer charges ahead with his vision of a TV network for rural America - despite some major bumps in the road.

|

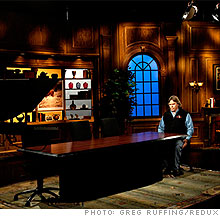

| Patrick Gottsch in the RFD-TV studios in Nashville. |

|

| RFD's programs include live cattle auctions. |

|

| Gottsch travels by chartered jet from Omaha to Nashville. |

|

| Gottsch prepares to record a promotional spot for RFD's new high-definition channel. |

OMAHA (Fortune Small Business) -- On the wall of a log cabin overlooking the Elkhorn Valley in Nebraska hangs a black-and-white picture of Patrick Gottsch as an 11-year-old with his father, also named Patrick. The youngster and his dad are both driving tractors through a cornfield on the family farm near Omaha. Gottsch is deeply proud of his country roots.

"Just like any other farm kid," he says.

Few farm kids express their love for country life as grandly as Gottsch has. Over the past 23 years the 54-year-old entrepreneur has built a small but growing media empire. It is anchored by a TV network named Rural Free Delivery (RFD), after the 19th-century postal service. The channel's vision: round-the-clock content by and for rural America. RFD features shows from National Tractor Pulling to Cowboy Church, not to mention hours of live cattle auctions.

"RFD-TV is a sensation," says Bob Scherman, editor of Satellite Business News, a trade publication. "Pat has a consistent vision and has never given up. His tenacity is astounding."

It hasn't been an easy ride. Gottsch watched his channel sink into bankruptcy, then he rebuilt it into a network that today reaches more than a third of U.S. households. Last year he signed a deal to simulcast New York shock jock Don Imus, whose controversial talk show fits uneasily in RFD's lineup. Gottsch has run afoul of the FCC, made a few enemies, and seen his share of courtrooms. And he has much further to ride. His goal: build a larger audience and pull in more advertising dollars without losing his country roots - or his country viewers.

Gottsch dreamed up RFD-TV while sitting on the front porch of that log cabin, now his home office. It was 1985, and having long since left farming, he was running a satellite dish installation business in nearby Omaha. Every day Gottsch would drive off with a ten-foot C-band satellite dish on the trailer behind his pickup, offering free trials to farmers and small-acreage owners.

"We always followed up on the phone or in person to ask if they liked the system," Gottsch recalls, "and always tried to pop them for referrals."

Then one day a customer asked whether there were any TV channels dedicated to covering rural America. No, Gottsch had to reply. His log cabin epiphany came soon after.

"Suddenly I thought, Well, shoot, there's nobody else going to do it, so why don't I?" he recalls with a smile. "I didn't know any better, so I did."

RFD-TV's first incarnation launched on C-band satellite in 1988. At that time there were fewer than half a million C-band satellite owners in the U.S. Proving the audience to advertisers wasn't easy. The company went bust, Gottsch says, after funding fell through and debt piled up. A 1989 Chapter 11 filing rated RFD-TV's liabilities at more than $3 million, against total assets of $1.8 million. The company went into Chapter 7 liquidation soon after.

Gottsch blames his late uncle Robert Gottsch, who he says offered transitional financing and then took control of the company before it filed for reorganization. But Jim Odle, a longtime investor in RFD-TV, says the channel was doomed by its overreach.

"Patrick took a pattern from a larger network," says Odle. "He had too much overhead, too much hardware. From day one he was operating in the red. He just couldn't catch up."

In 2000, against the advice of friends and family, Gottsch relaunched RFD-TV. Media technology had finally caught up with his vision. Satellite dishes were now smaller and cost $500 a pop instead of $2,000. The number of satellite subscribers had grown by a factor of 32. He had learned his lesson, and would run his business on a shoestring. In a crucial move, RFD-TV would be organized as a nonprofit entity.

RFD's new nonprofit status allowed Gottsch to snag a heavily discounted channel reserved for public-interest programming on EchoStar's (SATS) Dish Network. For the first few months RFD-TV carried just five hours of programming, played on 24-hour repeat each week. Over the next few years, Gottsch steadily expanded his lineup.

In 2003, Gottsch launched RFD-TV the Magazine, which at first offered little more than the channel's listings. The subscription price: $30 a year. "Everyone said I was nuts," he says. Five years later the magazine reaches more than 150,000 paid subscribers with listings and features on upcoming shows. ("Even my dad pays for his," Gottsch says.) The magazine has generated roughly $1.5 million in profit in each of the past five years.

Meanwhile, Gottsch's TV operation came under siege. In 2005 agricultural media company Farm Journal filed a petition with the FCC claiming that RFD-TV was improperly using its nonprofit status as a cover for commercial operations.

"This channel professes to be all about America and apple pie, but they gamed the system," says Jeff Pence, president of digital media at Farm Journal. "There should be a level playing field."

Four other Gottsch competitors and Free Press, a media-reform advocacy group, filed in support of Farm Journal's claims. In its December 2006 ruling, the FCC agreed that RFD-TV did not qualify for nonprofit or public-interest benefits.

The main evidence, the feds said, was the "special relationship" that existed between RFD-TV and Superior Livestock Auction, a for-profit, Fort Worth-based company that broadcasts call-in cattle auctions. According to the FCC, RFD-TV abused its nonprofit status by deliberately excluding other auction companies in order to help Superior, which also happened to be one of the channel's most generous sponsors.

Gottsch denies that there was ever a special relationship between his company and Superior. Broadcasting other cattle auctions would simply have taken up too much of RFD-TV's broadcast schedule, he claims. And he vehemently denies allegations that he ran a commercial business under nonprofit cover. "I went five years without a salary putting this program on as a nonprofit," he says. "That's not trying to beat the system."

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More