Black Diamond's death-defying revenue climb

An elite mountaineering outfitter aims for the mass market.

|

| Black Diamond CEO Peter Metcalf (right) and quality-assurance manager Kolin Powick on a ridge in Little Cottonwood Canyon in Utah. |

|

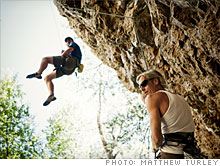

| Black Diamond sales chief Chris Grover belays staffer Andy Merriman. |

(Fortune Small Business) -- For Peter Metcalf, making a small business big is a matter of doing things in proper style. For this human StairMaster, that means taking the time to climb a combined 17,500 feet of Utah peaks on his 53rd-birthday weekend, toting a fine champagne for a summit party with family and friends.

Metcalf runs Black Diamond Equipment - a brand leader in the world of high-performance climbing and backcountry skiing gear - in his own unique way. Black Diamond is staffed mainly by elite mountaineers who design top-quality gear for their fellow athletes. And Metcalf's management philosophy evokes a hippie commune more than a typical U.S. corporation: Decisions here are made almost exclusively by committee.

Metcalf, who co-founded Black Diamond with a $744,000 investment and has grown it to reap an expected $90 million in sales this year, is readying for his biggest climb yet. He wants to double his revenues in the next five years. He just opened a sales and support center in Switzerland and a manufacturing and distribution facility in southern China. And he recently launched several new products, including portable LED lights for climbers and the first new ski boot in two decades to have been entirely designed and developed in the U.S.

As his business grows from small to large, Metcalf's definition of proper style will face a stiff challenge. This former full-time climber, who once slept in storm drains to save money between first ascents in Alaska and beyond, plans to execute his grand design without applying many of the models taught at business schools.

Black Diamond employs few career managers and even fewer MBAs. Instead, the Salt Lake City - based company hires mostly world-class athletes and outdoor enthusiasts. The standing joke among the staff is that the white-water, adventure-sports, and climbing champions on the payroll are better at their sports than most of the expert climbers and skiers who come to Black Diamond looking for sponsorship deals.

"We only want employees whose lives have been forged by competitive sports, who are passionate about the outdoors and damn good at what they are hired to do," says Metcalf. "Because of that outdoor experience, they know that their well-being is dependent on the well-being of the group. In most companies you advance at the expense of the other guy. Here you need that other guy."

In a business culture that often rewards entrepreneurs who concentrate on immediate profit, Black Diamond also stands out for its long-term focus. Metcalf shoots for slow, consistent annual growth - 13% is about average, rising to 20% in a good year. And from a customer-service point of view, Black Diamond caters primarily to a small community of elite mountaineers. So are Metcalf and his fellow climbing mavens up to the task of building a major corporation? Or is Black Diamond stepping off into thin air?

in some ways Black Diamond seems an unlikely candidate for mass-market success. First off, mountaineering is an extremely dangerous activity, which creates serious liability concerns for a company like Black Diamond, particularly as its customer base grows beyond hard-core mountaineers.

Most serious climbers take responsibility for their own safety. But any idiot can walk into a Black Diamond dealership, buy a climbing ax without so much as a question - much less a permit - head for the nearest glacier, and do himself in. Metcalf and three other managers founded Black Diamond nearly 20 years ago after a predecessor company, Chouinard Equipment, was forced into Chapter 11 bankruptcy by a series of liability suits over the deaths of several climbers equipped with Chouinard gear.

According to Metcalf, Black Diamond has been on the receiving end of only three liability suits in the past two decades, none of which damaged the company materially. But every year roughly one staffer or sponsored athlete dies in the field. While I was visiting Black Diamond in mid-August, 11 climbers died while scaling K-2 in northern Pakistan. Not a single person at the company thought it worth mentioning. While that might seem callous, it really shows that the threat of death is central to Black Diamond's culture and business model.

"The fact is, if one of our pieces fails, somebody could die," says Dave Mellon, vice president for R&D and product development at Black Diamond. "We take that responsibility on for everything we make. For us to grow like we have to, our customers need to know that we're committed to the products."

Unlike many manufacturers, Black Diamond does not seek to mitigate risk by relying on third-party insurers, testing companies, or outsourcing partners. Rather, it concentrates its risk by doing almost everything itself. The company is mainly self-insured. Black Diamond - break out your pencils - originates, designs, develops, tests, manufactures, markets, distributes, and in some cases sells directly the vast majority of its very complex line of products.

The strategy made perfect sense once I had spent a few days climbing, skiing, and hiking with Metcalf and the rugged outdoorsmen on his payroll. On the first morning they took me to Steort's Ridge, a 5.6-rated climbing face in Big Cottonwood Canyon, near Salt Lake. I made my way down a sheer 200-foot rock face, controlling my speed with a Black Diamond harness and braking device. (Let's just say I was very grateful for the two Black Diamond staffers, who told me exactly where to put my feet and hands.) If the gear had failed, I would almost certainly have fallen to my death. Only a suicidal climber wouldn't want to know exactly where his equipment came from.

Black Diamond's emphasis on vertical integration flows directly from the company's outdoor culture. And that brings me to a crucial point about Black Diamond's relationship with its customers: The company knows its market intimately because employees see a piece of it whenever they look in the mirror.

"That is the power of that brand," says Mike Wallenfels, president of Mountain Hardwear, an outdoor-apparel and -equipment maker based in Richmond, Calif. "The company is known for engineering everything to the highest possible standard based on their own experience as expert climbers. So other climbers trust them."

Manufacturing, designing, and testing thousands of product variants takes a brutal toll on the closely held firm's overhead and (undisclosed) profit margins.

"It's unlikely that Black Diamond could be a successful public company," says Matt Hyde, executive vice president of REI, the outdoor-equipment retailer based in Kent, Wash., and Black Diamond's biggest customer. "They're just not that profitable. But they make terrific products, and our customers respond to that. Black Diamond is a great brand in our stores."

Metcalf estimates that his total workforce, including line workers, exceeds 450. Every day Metcalf and his core managers struggle to reach consensus on a vast number of business decisions: the exact thickness of an ice tool, minute steps in the manufacturing process by which carabiners are attached to harnesses, marketing plans for the new ski boots, whether or not to include a particular type of LED light in next year's line. Those issues and many more get resolved in grinding, lengthy, and not particularly pleasant meetings. The Black Diamond management "secret" is exactly this: Fight it out until everybody agrees.

"There is not a product we make that didn't turn out better because of the time and energy we took to get to an agreement on what was best," says Metcalf.

This consensus-driven approach comes straight from the staff's outdoor experiences. In Black Diamond's so-called dawn patrols, staffers get up at 5 A.M. to climb and ski before work. One morning I joined three executives for a 3,300-vertical-foot hike up Grandeur Peak in the Wasatch Mountains, on the edge of Salt Lake City proper.

My climbing partner is Bill Crouse, Black Diamond's international sales manager. Crouse, 42, has been on Everest's brutal north face at least six times. My mountaineering skills are strictly amateur. But today we're partners, which means that my opinions count just as much as his. After all, if something goes wrong for one of us, it goes wrong for the other. Out here, and at Black Diamond, everyone is a partner who must be trusted and listened to.

"Even the best climbers need people around them," Crouse says at the summit, as we watch the sun rise over Salt Lake City. "Jerks are dangerous up here. Humility, cooperation, and focus are what keep you alive."

So can this niche company make it big? To find out, I caught up with Black Diamond at the Outdoor Retailer Summer Market in Salt Lake City, an annual salesfest for summer outdoor gear. Most of the nation's specialty retailers come to this multiday event to find merchandise for the coming year. At Black Diamond's large but simple show booth, the company's sales reps are indistinguishable from its customers. The chatter is mostly about some great climb in Nepal or the best route up to the high lakes in Chile. Product and pricing hardly even come up.

Today I'm hanging with Chris Grover, 54, Black Diamond's head of sales. Grover was an early climbing partner of Metcalf's, and he has been with Black Diamond for nearly two decades. He ticks off the summer product line: Ice tools. Harnesses. LED lights. And when we get to backpacks, he stops.

"We do maybe $1 million with these," he says. "Should be ten." Why's that? "Because we haven't yet cracked the Black Diamond essence of what a backpack should be."

When I press Grover to explain this Zen-like observation, he walks over to the trekking poles on display. "These are poles your mom can use to walk on ice better," he says earnestly. "Or you can use them to climb at 18,000 feet. We used to sell a few-hundred-thousand dollars in trekking poles a year. But then it dawned on us that we could treat our poles like bike frames and engineer the crap out of them. We extended the tube diameters, improved the cork handles, developed the strapping, and worked in our flick-lock system. And sales have doubled every year since then.

"Once we get that down for packs, they will do $10 million for us," Grover continues. "And why can't we do that for stoves? Or tents? It has to have something that we can sink our teeth into, and we are just scratching the surface of what that is." ![]()

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More