Inventor's killer sounds scatter pirates

After three decades and 300 patents, a San Diego audio entrepreneur found the secret to putting his company in the black.

|

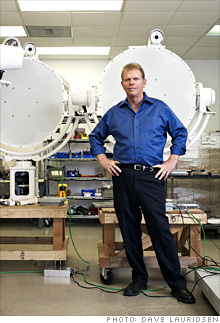

| American Technology Corp. founder Woody Norris |

(Fortune Small Business) -- Woody Norris has little passion for business. When it comes to technology, the 71-year-old founder of American Technology Corp. (ATC), a San Diego acoustic engineering firm, talks with the air of an enthusiastic teenager, telling you how "psyched" he is about his latest "cool" prototype. But ask Norris questions about corporate finance, and he'll shrug.

"I'm an inventor," he says. "I don't enjoy running the business."

He's not kidding. ATC has struggled since Norris started it in 1980, and it's never turned a profit. But the company's fortunes have finally changed, thanks to one of Norris's cool products - the LRAD, or Long Range Acoustic Device. The gadget looks like an enormous satellite dish and produces a bone-rattling noise. It's not a loudspeaker for rock concerts but a nonlethal weapon that has kept Somali pirates and Iraqi jihadists at bay.

The LRAD is the latest invention to spring from Norris's restless brain. The son of a coal miner, Norris spent much of his childhood tinkering with old radios in the family's chicken coop in Barrelville, Md. In the 1960s he developed the audio technology behind the sonogram. More than 300 patents later he'd earned enough in royalties to buy a 20,000-square-foot mansion on 44 acres outside San Diego.

But getting rich off royalty checks is not the same as making smart business deals. Norris once invented a headset that transmits sound through the wearer's skull. He sold the technology for $5 million to a San Diego communications company that later became Jabra. A few years later, Jabra sold it to the Danish firm GN Store Nord for $75 million. Norris doesn't lament the $70 million that got away, even though his company is in debt to the tune of $73 million. (ATC is entirely financed by equity; currently the largest shareholder is New York City hedge fund AWM.)

ATC's turnaround began with a Pentagon contract. In 2000 the U.S. Navy offered Norris $25,000 to help create a weapons-grade audio device that could stop small vessels from approaching U.S. warships. The goal was to prevent a repeat of the al-Qaeda attack on the U.S.S. Cole in Yemen that year.

At the time, Norris was working on his Hyper Sonic Sound (HSS) technology, which uses highly focused ultrasonic waves to "throw" sound to a specific location. HSS has been used in retail displays that talk to passersby without disturbing others on the street. Norris claimed HSS would replace home speaker systems, though acoustics experts say the sound quality is less than crystal clear.

"Woody Norris is given to elaborate exaggerations," sniffs Floyd Toole, a former vice president at Harman International Industries, an audio and electronic products manufacturer.

The LRAD, however, doesn't require high fidelity. Its noises are intentionally disturbing: Think fingernails down a blackboard or a baby's cry played backward. The sound waves are focused in such a way that the LRAD's operator hears nothing, while its target hears the noise at 95 decibels - about as loud as a subway train screeching to a halt right in front of you, but more consistent. "It won't permanently damage anyone's eardrums," Norris says. "But at 400 yards it's loud enough that you're going to get the hell out of there." Norris and his engineers delivered a prototype LRAD to the Navy within months.

Private shipping companies concerned about piracy began to show some interest. In 2005 pirates in two speedboats attacked the cruise ship Seabourn Spirit off the coast of Somalia. Luckily, the Spirit carried an LRAD. Security personnel beamed a series of earsplitting bangs at the speedboats, buying the ship time to move out of range of the pirates' rocket launchers.

The U.S. Marines adopted Norris's device for crowd control in Iraq. At checkpoints in Baghdad and Fallujah, they used their Humvee-mounted LRADs to blast a series of Arabic phrases, such as "Go away or we will kill you." The Marines say the LRAD has an unparalleled ability to disperse crowds - and they've never had to follow it up with deadly force.

Meanwhile Norris started to take his business more seriously. In 2006 he hired a new CEO, Tom Brown, a former president of Sony Electronics. Brown cut costs by manufacturing locally and reducing head count, and focused sales efforts on large clients. ATC customers have included the New York Police Department, the organizers of the Beijing Olympics and the governments of India, the Republic of Georgia and the United Arab Emirates.

In 2008 ATC's revenues grew 10%, to $11 million. The company, which has 35 employees, saw growth of 140% in the fourth quarter alone, thanks entirely to LRAD orders. ATC sells a few other products, such as SoundSaber, an ultrathin speaker technology, and SoundVector, a sonic alarm. But the vast majority of the company's revenues - 80% - come from LRAD sales. (An 18-inch LRAD sells for $20,000, while the 40-inch version costs $30,000.)

Norris still has the ability to throw away a competitive edge: He didn't bother to patent the early-model LRADs because he considered the technology "rudimentary." (Patents are pending on components of the current models.) Two firms, both launched by former ATC employees, sell products designed to compete with the LRAD - the Hyperspike system made by Wattre, based in Woodburn, Ind.; and the SoundCommander from IML in Marietta, Ga. Each company, unlike ATC, is privately held and doesn't release sales data.

One thing is certain: They have received fewer government contracts than ATC. In 2007 the Navy tested the LRAD head-to-head against its two rivals. The official test report said Norris's product offered better range and clarity, which led to a flood of military contracts for ATC.

With Brown looking after the balance sheet, Norris is psyched: He gets to tinker with dozens of ideas for cool products. (One potential prototype: an ultralight personal helicopter.)

"I don't think very much has really been invented yet," he says. "I think the good stuff is on the near-term horizon." ![]()

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More