The anti-iTunes: Forgotten rock for sale

An all-digital music label digs up treasures from pop history.

|

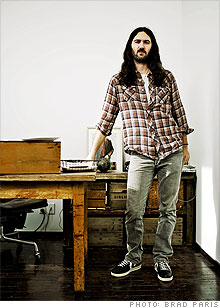

| Keith Abrahamsson, owner of Anthology Recordings |

|

| A classic Moby Grape album gets a spin on Anthology's turntable. |

(Fortune Small Business) -- In his compact New York City office, Anthology Recordings owner Keith Abrahamsson sits at his computer examining a list of recent customers. It seems that Monika from Denmark just spent $29.94 on three albums from his label, including Inside the Shadow by Anonymous. "That's an amazing record," he says, nodding approvingly. "I feel honored to work with a record like that."

Anonymous was a 1970s midwestern band that played chiming folk rock not unlike the Byrds. This is obscure stuff, even for devout followers of vintage rock. But that's the point. It's a music business truism that back catalogues, particularly reissues of classic albums - such as Pink Floyd's 36-year-old masterpiece Dark Side of the Moon, which still sells about 10,000 copies a week - can equal big money. But is there a market for music so underground that few people bought it or even heard it the first time around?

Abrahamsson thinks so. In 2005, while working at his day job (as an A&R man at indie rock label Kemado Records), he dreamed of starting his own company. He briefly considered opening a record store but nixed the idea because it "just seemed suicidal in this climate." Instead, inspired by the cultish hard rock albums of the '60s and '70s that his father once played for him, Abrahamsson created something new: a label that would specialize in long-forgotten albums and distribute music only digitally - no CDs allowed. Says Abrahamsson, "The criteria is 'never too obscure.'"

Launched in October 2006 with only a handful of releases, Anthology now offers 500 digital albums by esoteric acts such as My Solid Ground, a German psychedelic band from the early '70s; British folk rockers Love Exchange, who enjoyed a brief vogue in the late '60s; and even Bobby Beausoleil, a Charles Manson associate and composer who is currently serving life in prison for murder. Anthology's prices - about $10 per album - are low compared with costly bootlegs of the same albums.

"There was a gap in the market for these kinds of records," says Abrahamsson, 32, who closely resembles a musician from about 1973, complete with long hair, beard and flannel shirt. "iTunes doesn't have a lot of this music or real obscure stuff. We're going to grab that market."

Anthology's digital-only route makes economic sense - especially in the current business climate - and keeps costs low. Because the label doesn't have to press actual CDs or booklets, it makes money off sales almost immediately; in a good week it sells $2,000 worth of music. It also helps that Abrahamsson doesn't offer advance money to any of the bands. Instead, he gives them about 70 per song or album sold. He doesn't even pay rent: Because his entire operation is digital, he runs the business out of his Kemado office, with his boss's blessing. His biggest monthly expense is computer storage for his growing music collection.

Even startup costs were low: a mere $20,000. Abrahamsson put up half, and the rest came from friends, some of whom received stock as compensation. One full-time employee and one part-timer help him track down the master tapes of out-of-print LPs (the label adds five to 10 new albums a month) - and the people who made them. Sometimes the label's overtures aren't welcome. One aging Boston-area punk rocker said he'd rather "eat sh-t" than work with Anthology, then changed his mind and allowed that he might if Abrahamsson wired him $2,000 that day. (Abrahamsson declined.)

Most, however, seem flattered that anyone remembers their long-forgotten, long-unavailable music. Tom Nardi, one-time bassist in the Trenton psychedelic garage band Sainte Anthony's Fyre - the group's sole LP, from 1968, was one of Anthology's first reissues - has made only about $100 from the rerelease but isn't complaining.

"It's nice to get the checks," says Nardi, 57, who now works in construction. "And it's amazing that, after 40 years, the music is still out there." ![]()

Becoming Ben Taylor

A look at a music CEO's iPod

The iPhone music maker

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More