How Monster Cable got wired for growth

Monster Cable founder Noel Lee has come a long way from his family's garage.

|

| Monster Cable CEO Noel Lee |

|

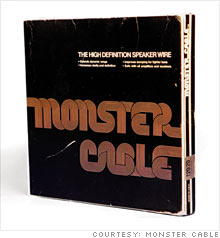

| Early Monster Cable packaging |

(Fortune Small Business) -- Noel Lee trained as an engineer and aspired to be a rock star but became neither. At one point he played drums with a rock cover band in Waikiki between stints at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a government nuclear research center near San Francisco. But ultimately Lee paired his passion for music with his exacting standards as an engineer to create a high-performance alternative to simple lamp wire - and built Monster Cable, a resounding business success.

Lee, 60, founded Monster in 1979 in his family's San Francisco garage. He now has 550 employees at five locations around the world: the company's Brisbane, Calif., headquarters and offices in Las Vegas, Ireland, England and Hong Kong. The privately held firm does not reveal its revenues but is estimated to bring in more than $100 million annually.

Until Monster came along, hi-fi dealers typically provided free lamp wire to hook up speakers and stereo components. Today Monster's wires and cables are only one part of its product story. The company makes everything from iPod accessories (the one product area Lee says requires no consumer education on his part) to specialized surge protectors that prevent power from flowing the wrong way through a home theater system.

On a sunny afternoon, Fortune Small Business sat down with Lee at a Hillsborough, Calif., sidewalk caf to find out how he got started and what it means to do things the Monster way.

LEE: Music is my passion, and it occurred to me that the wires people used to connect their speakers to their home stereo systems were not constructed in a way that provided the best listening experience. In those days speaker wire was an afterthought.

I started testing different wire options at home, varying the thickness, composition and braiding pattern, and listening to Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture again and again through each test cord, until I found the best possible construct.

Listening to wire is a learned process, like wine tasting. You must listen for many things at once - dynamics, loudness, bass response, high frequencies - so you need a piece of music that contains all those elements. [Later, Lee would use Michael Jackson's "Liberian Girl" from the album Bad as his test song.] I would go back and forth between one wire structure and another, listening to the same song thousands of times. Then it was time to show off what I'd learned.

But I'm an engineer, not a businessman. I think that if I'd had more business knowledge and sense in the beginning, I might not have even tried to introduce Monster Cable to the market. At first I couldn't get a loan. For two years the bank turned me down, even though I had a great business plan and my mom's house as collateral. Finally I found out that the head of the loan committee just didn't like music. I realized I had to shop around until I found a bank where the loan officers were also audiophiles! Banks are not big risk takers. If you're an entrepreneur, wherever you go for your money, make sure your banker relates to your vision.

Even after I got started, I had trouble getting enough credit to keep moving forward. When I was about two years into the business, one Canadian distributor wanted to buy about 35,000 units of my product - the biggest order to that point - but would pay me only once the wires had shipped.

The problem was, I needed the money to actually make the product. I went to the bank, and the bankers said, "Show us the product." So I mocked up a stack of boxes, putting boxes full of packaged wire on top and empty boxes below. The bankers saw the large stack and said, "Okay, you're good to go." Thank goodness they didn't open the bottom boxes.

At first it was one store at a time. An early customer, Pacific Stereo in Emeryville, Calif., told me that Monster was a bad name and would hurt sales. The retailer had a presence in California and was making moves toward the East, and I knew that was where I needed to be to grow sales. But when I went to the buyers, I basically had the door slammed in my face. Maybe if I were starting out today, with blogs and online customer interaction, I wouldn't have to knock on so many physical doors. But I would still need to be an educator first and a salesman second.

Finally I got an appointment with Richard Strand, Pacific's vice president of merchandising and a true audiophile, to present my product. He had no idea if it would sell, but he said, "Since you're such a believer, Noel, I want to give it a shot."

So Pacific took a gamble on me and eventually became a great customer, although it has since gone out of business. The challenge with these stores was to educate hi-fi experts so they understood that they were missing one of the most important elements in providing the best audio experience to their customers. I would demonstrate the difference between my wire and theirs, right there on the sales floor. I had to create a market where none existed. In the beginning we called it a cure without a disease.

Besides going store to store, I bought space at half a table in a 10-by-10 booth at the 1977 Summer Consumer Electronics Show. I drove to Chicago with a load of wires for that show. I made my first boxes by hand, and I used rub-on letters and photocopied labels for the packaging and signs. But the labels came out too light, so I bought black felt markers and darkened each by hand. Still, people at the show said they liked the packaging, the idea and our name.

At this point we were still working out of the garage in my family's house. The first production table was a four-by-eight piece of plywood and two sawhorses. I bought a pneumatic pump to wind up the cable, cut it, terminate it and put it in boxes. And that was the Monster Cable factory.

After Pacific Stereo my next big account was Crazy Eddie [now also out of business] in New York City. After that we started to pick up steam. By the end of 1977 we'd moved from the garage to our old company location at 101 Townsend St. I also hired my first employees outside my family: Tai Min and Shang Yu Change, who are still with the company today.

Throughout Monster's existence I've been approached by people who thought they had great plans for partnerships or who wanted to take us public. I knew it was important to stick to my mission for Monster, and I fended them off. Staying independent has been very good for us. But as a businessperson I have been forced to learn some tough lessons.

A few years ago we had to move jobs out of the San Francisco Bay Area. [Lee laid off about 120 production employees, earning him criticism from local officials and activists, who were upset that at around the same time the company chose to become the primary sponsor of Candlestick Park, the home of the San Francisco 49ers. The stadium was renamed Monster Park under a four-year deal that cost $6 million. Half of the money went to San Francisco's parks department - an important component of the deal for Lee.]

Silicon Valley is an expensive place to manufacture, and hanging on to those operations could have done real damage to our long-term business health. Monster was the last of the cable companies to assemble products in this area.

I'd never had to work through the issue of layoffs before, but I learned that I needed to constantly ask myself, "Do I have the right labor force to accomplish what I need to do for the health of the company?"

The main lesson I took away is that I held on longer than I should have. I should have been willing to make those personnel changes even earlier. Everyone else was already outsourcing this type of activity outside the country, most often to Asia. So finally we moved that part of our operation to Mexico.

Ultimately you need more than a good core mission and passion. You must be willing to acknowledge your weaknesses. When business is good, you can have fundamental problems and still survive. When business is bad, you're doomed by those flaws.

A small business guy has to recognize he doesn't know everything he needs to know. You have to find good advisers. We've paid a lot of money to consultants over the years, but really they are committed to making you rely on them and not necessarily to providing the best solutions for your business.

No matter how large or small your business or your goals, you must remember that when it's your money, you make the decisions. You can never abdicate that to someone else. ![]()

Fixed in the USA (but made overseas)

Free advice: Priceless

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More