Soldiers. Park rangers. IRS agents. They all have access to one of the cheapest retirement savings plans available. Yet some are giving up their low-fee plan -- and they are paying thousands of dollars more in fees as a result.

The Thrift Savings Plan, used by millions of federal workers, is like a 401(k), except it's a lot cheaper. Last year it charged an average expense ratio of a mere 0.03%. That means just $3 in fees for $10,000 in savings, or $30 for a $100,000 portfolio.

IRAs or employer-sponsored 401(k)s typically charge more than 10 times that amount.

Nevertheless, federal workers are rolling billions in savings out of the low-fee plan when they leave their jobs, even though they don't have to.

Last year nearly half (45%) of participants who left federal service in 2012 had withdrawn all of their savings -- nearly $10 billion collectively.

Workers on government message boards cite a number or reasons for leaving, including frustration with the thrift plan's limited investment options and strict withdrawal rules.

Spokeswoman Kim Weaver said TSP officials are currently reviewing the plan's withdrawal options to see how they might be changed, and that the agency wants to make sure workers "understand all the costs that they will be paying once they roll their money out of the TSP."

Related: What I gave up to save $1 million

But some retirement savings experts suspect that a heavy sales pitch by private financial firms and advisers might also be a factor.

Gregory Long, the executive director of the agency that runs the thrift plan, wrote in a memo that he thinks some federal workers and retirees may be "swayed by the financial industry's marketing efforts" to roll their money out of the low-cost plans into higher-cost IRAs.

John Turner, an economist and director of the Pension Policy Center and a former federal worker himself, said he became troubled when he heard of friends who had pulled out of their funds only to pay thousands in fees.

As an experiment, Turner called up major IRA providers and asked for advice, explaining he was a former government employee with savings in the thrift plan. Only one firm acknowledged he could do better by staying with the plan's super low fees, while the rest all encouraged an IRA rollover.

Related: Is this retirement move right for you?

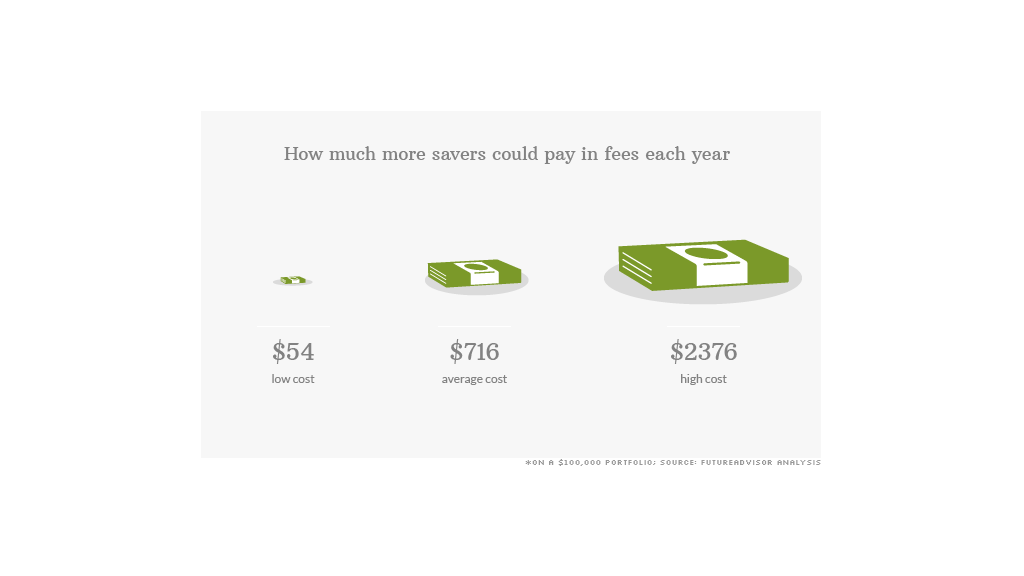

CNNMoney asked FutureAdvisor, an online investment advisor, to run some numbers to compare fees and investment returns:

Let's say a worker has $100,000 invested in the Thrift Savings Plan. Even if she rolled her money into the cheapest comparable ETFs on the market, she would still spend $54 more in fees each year despite getting similar returns.

If the worker were to roll that money into an IRA, invested in mutual funds with average fees of 0.74%, she would pay an extra $716, FutureAdvisor found.

And if she opted for a pricier portfolio, say one with fees of 2.4%, she could shell out more than $2,300 in extra fees in a single year.

"Over years, it's a substantial difference in what you end up with," Turner said. "It's not a trivial issue."

Related: Retirement plan providers misleading savers

To be sure, participants in the Thrift Savings Plan, which has five main funds, can find more investment options in private IRAs.

Yet Turner said the thrift plan offers enough stock and bond index funds that track domestic and international markets to give most savers what they need.

Military veteran Ryan Guina, who writes a military-focused personal finance blog, agreed.

"Unless they're advanced investors, I think they should leave their funds in the TSP because it's simple and it's easy enough that most investors can do it and do it well," he said.

FutureAdvisor, in its analysis for CNNMoney, found that typical investors can almost always get higher returns from the government plan compared to similar investments, especially after fees are taken into account.

Last year, for example, the thrift plan outperformed the sample high-cost portfolio by 3%.

So how does the government thrift plan keep fees so low? It partly subsidizes plan expenses with revenue from loans taken from the plan and forfeitures from employees who leave before fully vesting -- a practice termed "quite unique" by FutureAdvisor Chief Investment Officer Simon Moore.

"They are able to drive costs below market value, which is great for their investors," Moore said. "A corporation wouldn't do that."