A year ago Friday, Amazon announced its quest to find a city for its second headquarters somewhere in North America.

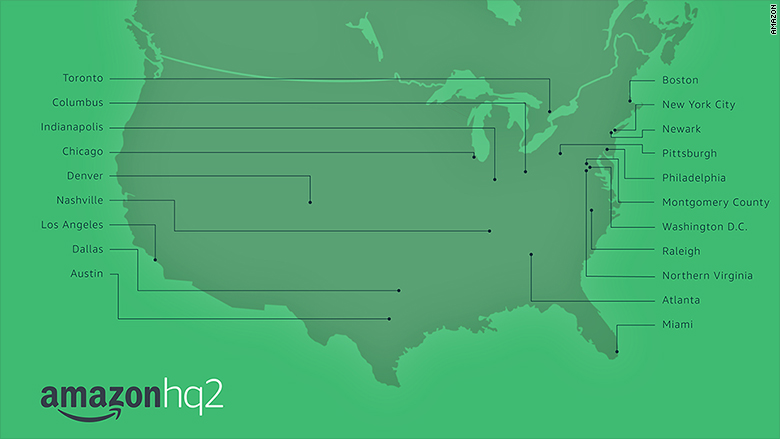

The company has since whittled down 238 proposals to 20 finalists. Executives have crisscrossed the United States -- and one Canadian city -- to tour sites in search of the company's next home. A decision is expected this year.

If anything, the past year reemphasized one thing loud and clear: Amazon knows exactly what it's doing. The process has given the company a trove of free data about cities and drummed up tons of free publicity and hype.

Experts say the public nature of the search made the process unique. Businesses traditionally approach a handful of cities quietly rather than create an open competition.

But Amazon's promise to spend $5 billion to build its HQ2 facility and create 50,000 jobs ignited a frenzy among cities vying to boost their economies. The new facility is expected to be an equal to its Seattle headquarters.

Amazon has a few guidelines for its new campus: proximity to a major airport, ability to attract tech talent and a suburban or urban area with more than 1 million people. Cities responded with splashy campaigns. Tucson, Arizona, famously sent Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos a giant cactus, and Birmingham, Alabama, installed massive Amazon delivery boxes around the city. Other places like Newark, New Jersey, and Montgomery County, Maryland, dangled big tax breaks.

But there's something much bigger at play. Through the process, Amazon has gathered a massive amount of data about participating metro areas, such as details about their labor force, quality of life, access to mass transit -- and arguably, most importantly -- their willingness to pony up huge incentives to attract the company.

The data could be useful for Amazon when deciding where to open future warehouses, fulfillment centers and smaller corporate offices. The information, particularly tax breaks, could also give the company an advantage in future negotiations with that city.

"Cities are working so hard to draw attention and be on the map with Amazon," said Nick Vyas, executive director of the Center for Global Supply Chain Management at the USC Marshall School of Business. "This could literally change the game for the city, county, and the state for that matter."

The public search for a HQ2 host city isn't the only unusual element: The amount of jobs that comes with it is also rare.

"You don't see this scale very often," said Nathan Jensen, an economist at the University of Texas at Austin. "[50,000 jobs] is an incredible single shot to the arm of a local labor market."

Even if a city doesn't win, advantages can still exist for participating candidates, such as other investments from Amazon.

"At the very least, these cities tried to figure out how to best pitch their city for economic development," said Jensen. "[They created] a thoughtful analysis of what makes them attractive for this kind of investment."

He says the process encouraged some cities who didn't make the cut to do some "soul searching" to evaluate where they came up short, which may help spur changes. Meanwhile, cities that were short-listed have already seen a rise in interest from other businesses as a result of becoming a finalist. For example, Philadelphia said several companies referenced its HQ2 bid efforts as a reason for an interest to set up offices in the city. Elm Partners, an investment firm previously based in London, is relocating there.

But its not just the final 20 cities that are getting attention. Several cities that submitted bids but didn't make the short list received an investment from Amazon directly. The company recently announced new fulfillment centers in Birmingham, Alabama; Spokane, Washington; and Ottawa. A new tech office is opening in Vancouver, as well. A source familiar with the HQ2 bids told CNNMoney in July the information from their proposals -- such as details about training programs and labor force -- helped these cities nab these deals.

However, experts also warn that vying cities must be careful not to give away too many incentives. To pay for local tax cuts, communities may have to increase taxes elsewhere or slash spending on public services like education.

Other negative ramifications could surface, such as an increase in housing prices and higher cost of living in the winning city. In addition, some communities have spent significant time chasing Amazon rather than focusing energy and resources on other economic development projects, such as how to help local businesses expand.

It's unclear if Amazon will release an even shorter list of contenders before announcing the winner. Amazon did not respond to a request for comment. Either way, all eyes are on the grand prize.

"Amazon continues to monitor how far the top 20 contender cities are willing to go in offering additional incentives in order to bring HQ2 home," said Ilir Hysa, senior economist at Moody's Analytics.