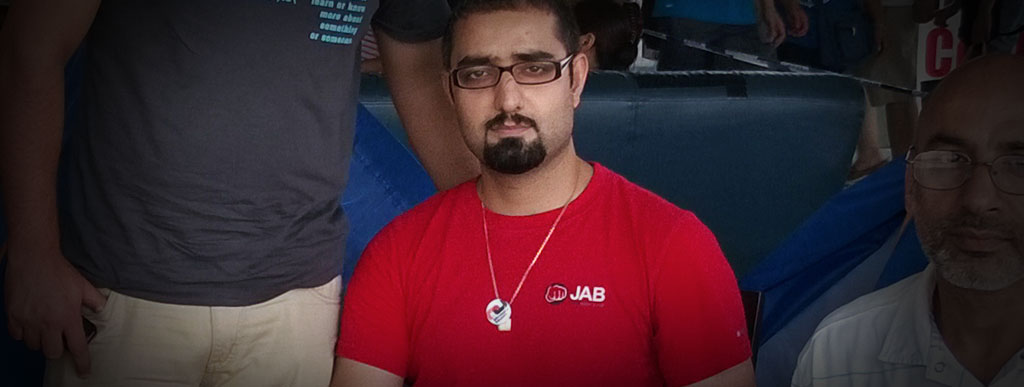

Mohammadi Rahman, 30, has been on the run for his entire life.

As a young man, he fled across the border from Afghanistan to Iran after his brother was shot during the country's civil war. He came to Hong Kong in 2007 in search of a better life, but has instead been caught in a draconian immigration system that is plagued with chronic delays.

Rahman – called Raymond by his friends – is one of thousands of refugees who are forced to live in squalor for years as their cases work through the system. While they wait, the Hong Kong government typically prohibits refugees from working. Instead, they receive some food and a housing stipend of 1500 Hong Kong dollars ($194) per month – a paltry sum in a city where even tiny studio apartments can rent for 10 times that amount.

Raymond is chairman of the Refugee Union in Hong Kong, a group that advocates for better conditions for refugees.

Here are journal entries from a day in his life:

I wake up tired because back pain kept me up until the early morning. My wife – who is not a refugee -- has already left for her job as a “foreign domestic helper” with a Hong Kong family. The job pays only 4000 Hong Kong dollars ($520) per month – much of which is sent to her family in the Philippines.

I make a breakfast of bread and jam, even though I’m not very hungry yet. I worry about my family members in Iran, a country that is very dangerous for Afghan refugees. I desperately want to help my mother and brother find a way to escape.

I eat in our apartment, which is very small and has a total area that is roughly the size of two double mattresses. The rent is 3300 Hong Kong dollars ($425) a month, and leaves us with so little money that we can’t even afford to buy a new toilet seat.

I am going to see a doctor today, but before I leave the apartment, I read a laminated card my wife has placed near our bed. The words might sound cheesy to many people, but I read them every day:

“Life is not about waiting for the storm to pass, but about learning how to dance in the rain.”

I’m taking the bus to a public hospital in Hong Kong’s business district. I choose not to have lunch, because if I did, I wouldn’t have enough money for the return bus fare. I’ve lost so much weight this year that I had to ask a friend to buy me new shorts.

It bothers me when I think about how much food is wasted in Hong Kong. When I first arrived in the city, I had to scavenge for food in supermarket dumpsters because I had no money. That was the first time I felt like a beggar.

The doctor says he can’t do much about my back injury, which is depressing. He can only give me pills that are supposed to help the pain. I don’t want to take so many pills, and the whole thing makes me feel like a throw-away human.

I go to the Refugee Union protest camp, which we have set up on a busy footbridge in Hong Kong’s business district.

We’re trying to draw attention to the rich-poor divide in Hong Kong, and the fact that people shouldn’t be deprived of human rights just because of where they were born or the passport they hold.

I’m feeling dizzy because I’m hungry and took medication on an empty stomach. Sometimes I even have trouble finding fresh water to drink in downtown Hong Kong, where there aren’t many water fountains. I can’t afford bottled water.

I’m still at the protest camp, and more refugees are stopping by. We mostly talk about our shared problems – including the fact that we’re not allowed to work. We don’t have an office, because that would be far too expensive. Thousands of people walk by the camp, but most probably think of it as an eyesore that should be removed.

After taking the slow way home because I can’t afford subway fare, I am finally back at the apartment to enjoy my wife’s beef curry, which I think is the best in the world. We eat on the bed and hold our plates in our laps. Tonight we have splurge on some Coca-Cola as a reward for enduring a stinking hot day.

My mother calls from Iran to ask how I am doing. I lie to her about the harsh conditions I endure because I don’t want her to worry more than she already does. I miss her more than words can say and hope we will someday be reunited.

My family trusted that I would reach a developed country, where I would be safe to work and earn money that would help them escape too. It devastates me that I have provided no help and let them down.

My wife and I watch the comedy “Hot Fuzz” as we fall asleep. I’ve seen it many times but understand the dialogue better and better as my English improves.

Watching a movie is about the only pleasure that I can share with my wife. But that doesn’t matter so much, because we love each other. I think it’s one way that I am luckier than most husbands.

Readers: What's it like to spend 24 hours in your shoes? Email blake.ellis@cnn.com for the chance to be profiled in an upcoming story.