Found in translation: Avoiding multilingual gaffes

How a small translation company helps big brands avoid global mishaps.

|

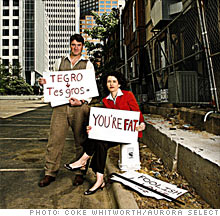

| Vernon and Michelle Menard with one of the product names they nixed |

(Fortune Small Business) -- When it comes to naming their products, many large U.S. companies have veered dangerously close to international embarrassment.

Take the pharmaceutical giant that wanted to call a new weight-loss pill "Tegro." It sounds harmless enough in English, but in French the word is phonetically identical to t'es gros, or "you are fat."

Then there was the name for a global technology training system that sounded exactly like the Korean for "porn movie." Not to mention the HIV medication whose German name could easily be mistaken for "foolish love."

Luckily for the companies involved, those gaffes were seen only by experts at a small U.S. company. Choice Translating, based in Charlotte, has found a profitable niche examining product names in multiple tongues.

"It's expensive to create a brand identity," says Vernon Menard, who co-owns the company with his wife, Michelle. "We're cheap insurance."

The Menards had no intention of getting into brand analysis when they started out. Michelle, 37, began the translation services company in the mid-1990s while studying French and business administration at the University of North Carolina. Vernon, 42, bought half the business in 1999; the pair married in 2001. Since then, Choice has built a roster of about 1,000 freelance translators in more than 80 countries around the world.

Soon, a local branding firm came calling. To evaluate how its clients' product names would sound abroad, this company had been using bilingual students in Charlotte. "They needed more resources," says Michelle, who jumped at the chance to leverage her network of translators.

By 2007, Choice Translating was making $600,000 from brand analysis, out of total revenues of $2 million. (Revenues in 2006 were $1.5 million.) The Menards hope that brand analysis will generate as much as 80% of their business within the next two years.

Clients pay about $13,000 for an analysis of their brand in dozens of dialects in target markets. The Menards built an online survey form so that freelancers in the target market could respond quickly. The questions are simple: Does the name mean anything in the target market (such as an antipsychotic medication that translated to "dogs are afraid of me" in Mandarin)? Does it have any negative connotations (such as the pill that started with the letters "Xep," which in Russian sounds like a slang word for male genitalia)? How easily can it be pronounced?

Once the results of the online survey are aggregated, Choice writes a report and sends it to the client, usually within five days of the original request. Addison Whitney, another brand-consulting firm based in Charlotte, used Choice for 90 projects last year, checking its clients' product names in as many as 30 dialects.

"Now is a good moment to do this," says Renato Beninatto of Common Sense Advisory, a market research firm in Lowell, Mass., that covers the language services industry. "American companies are looking to sell more products abroad because of the cheaper dollar."

Even the giants of the $4.9-billion-a-year U.S. language services market have a kind word for their small rival.

"They've found a nice little niche there," says Kathleen Bostick, vice president of global business at Lionbridge Technologies, based in Waltham, Mass. Lionbridge offers brand-name analysis as part of a suite of "localization" services, or if the client specifically requests it.

Late last year Choice added a visual-evaluation service. The firm's network of native translators examine corporate logos for colors, shapes, and symbols that have negative local connotations. For example, white may represent purity in Western cultures, but in China it is the color of death and mourning. Choice has so far completed five visual projects for two clients.

Choice last year opened a project management office in Lima, Peru, a city Vernon knew from previous business ventures. Today that office houses 15 full-time Choice employees, compared with seven in Charlotte. The network of freelancers requires good project managers, and "it was hard to find talent in Charlotte," says Vernon. "We were often dealing with the leftovers after the banks had their pick. In Peru we are a top-tier employer."

There's no mistaking what that translates to: better talent, lower salaries, and bigger profits. ![]()

How not to sell abroad: Check out our gallery of classic translation gaffes.

Translating your company around the world

Take your business global

Rocking the Casbah

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More