Life after your bank fails

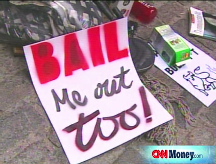

For small businesses with six-figure sums socked away, a bank failure can be a devastating blow.

|

| Fran Quittel lost $10,000 when IndyMac failed. |

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- When recruiting consultant Fran Quittel heard on her car radio one Friday afternoon in July that her bank, IndyMac, had been seized by federal regulators, she was surprised but unworried. An IndyMac customer for five years, Quittel had both personal accounts and business accounts at the bank, but she was confident her accounts contained less than the $100,000 insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

But as Quittel delved into her banking details that weekend, she got an unexpected shock. Her business savings account was temporarily sheltering a chunk of funds awaiting deposit into her 401(k), and her business checking account still contained the money for an uncashed payroll check. The combination pushed the total stored in her business accounts over $100,000 - and when federal regulators closed IndyMac, Quittel immediately lost access to a portion of her uninsured funds.

"I didn't realize how fragile the bank was," said Quittel, the owner of Frances Quittel Inc. in Emeryville, Calif. "If you're a small-business owner, you have cash moving in and out of your accounts all the time - you're putting in money to pay for taxes, to pay health insurance premiums, to pay for retirement account fundings. It just doesn't occur to you that you're playing Russian roulette."

Many small businesses run close to the bone, and don't have six-figure sums stockpiled at the bank. For those that do, the risk of a bank failure remains remote: Washington Mutual (WM, Fortune 500) was the 13th bank to fail this year, out of 8,500 banks in the U.S. The FDIC had 117 banks on its watch list at the end of last quarter, representing a small sliver of the industry.

If your bank does fail, though, it can take with it a sizable portion of your operating cash, if what you have stashed exceeds insured limits. When NetBank went under in September 2007, it held around $800,000 for Applied Cognetics, a four-year-old software development firm in Brooklyn, N.Y. The FDIC quickly repaid depositors for 50% of their uninsured balances, but Applied Cognetics was left for months short several hundred thousand dollars.

"We just had to tighten our belts and work harder," said Chris Coulthrust, founder and president of the 12-person company. "We were able to get back enough to pay all of our bills, and we're profitable, so we were able to write off a lot of the loss on our taxes."

Now with Bank of America (BAC, Fortune 500), Coulthrust is reluctant to open multiple accounts for his company at multiple banks. "If we get past $1 million in our account, I guess we would move it around and create another account, but to have your money in multiple accounts is a pain," he said.

That's exactly what the experts advise, though. Bruce Zicari, a CPA and the partner in charge of the small business advisory group of accounting firm Bonadio Group in Rochester, N.Y., said he's been fielding calls from clients this week asking how to safeguard their bank accounts.

"We've advised them to be sure to keep below the FDIC insurance limits in each account, and to open multiple accounts if they need to," Zicari said. "Unfortunately, it's not the most efficient way to do business, but this is uncharted territory we're in. In the past you kind of took bank accounts for granted, but now it's a real issue."

The best way for companies to guard their cash is to avoid keeping much of it on hand in the first place. Zicari encourages customers to pay for major purchases by borrowing against a line of credit, which they can they promptly pay off, a maneuver that keeps them from having large sums sitting at a bank. Corporate savings should be stashed in money market funds or in Treasury bills, he recommends.

Earlier this month, the Treasury Department said it would insure up to $50 billion in money-market fund investments at financial companies that pay a fee to participate in the program. The initiative, which lasts for a year, will guarantee that the funds' value does not fall below the standard $1 a share.

Nolan Newman, a partner in Seattle CPA and consulting firm Newman Dierst Hales, also backs T-bills and money market funds as good options for small businesses. Given the recent financial turmoil, Newman is encouraging his clients to respond by being proactive in their financial planning.

"Don't assume someone else is looking out for you; don't assume your business model won't be subject to stress," he said. "In the areas of collections, expense controls and discretionary expenditures, tighten up. If you are in negotiations to get a credit facility, move quickly."

In a poll of National Small Business Association members conducted this month, 68% of those surveyed said the FDIC's $100,000 insurance limit wouldn't be enough to fully protect their business accounts. The American Bankers Association, an industry trade association, recently published a list of tips for small business owners looking to protect their bank accounts. Among its recommendations: Use the FDIC's Estimator tool, available online at http://www.fdic.gov/edie/, to calculate whether or not your bank deposits exceed insured limits.

The ABA also recommends that small companies consider tapping CDARS, a five-year-old system designed to offer FDIC protection for amounts far greater than the standard $100,000 limit.

CDARS, which stands for Certificate of Deposit Account Registry Service, is a financial service created by the Promontory Interfinancial Network in Arlington, Va. CDARS works by farming out large deposits across multiple banks within its network. Funds are then invested incrementally in multiple CDs, with no single bank holding more than $100,000. If any individual bank fails - as several CDARS members have - the CDs it holds will be of a low enough value to be fully covered by the FDIC.

CDARS is free to depositors, and can insure deposits of up to $50 million. Member banks pay a one-time fee to join the network and thereafter pay transaction fees on the funds they pass through CDARS. Most of the network's 2,500 banks are small community banks - the average asset base of members is $250 million, according to Mark Jacobsen, president and COO of Promontory Interfinancial Network.

Businesses make up the bulk of CDARS customers, accounting for 37% of its volume. Individuals, public entities like local governments, and banks themselves are also major customers.

"What small businesses like about CDARS is that they can deal only with their local institution and still protect their deposits," Jacobsen said.

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More