Love a local business? Buy a share

Sometimes it takes a village to fund a company.

|

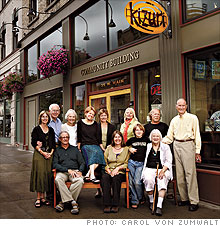

| Local investors gather around Kim Harmson (center, in skirt), owner of the Kizuri fair-trade shop in Spokane. |

|

| Comfort Lounge owner John Halko reveals his fundraising strategy: VIP treatment for shareholders. |

|

| Diners sample Comfort food. |

HASTINGS-ON-HUDSON, N.Y. (Fortune Small Business) -- John Halko was halfway through renovating an expanded space for Comfort, his mostly organic eatery in Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y., when the credit crisis hit. His source of funding -- a home-equity line -- ran out, so he applied for a loan at a local bank. He was turned down.

Halko wasn't ready to throw in the dish towel. His solution? The modern equivalent of an old-fashioned barn raising. Instead of soliciting neighbors to lift timbers, he asked them to open their wallets. For every $500 they purchased in "Comfort Dollars," his patrons received a $600 credit toward meals at the restaurant. As the community rallied around Comfort, Halko says, "it gave us hope." He raised $25,000 in six months, and the new, larger space - now called Comfort Lounge -- opened for business in May.

Plenty of entrepreneurs are turning to their communities for support in these tricky times. As the recession wreaks havoc on America's economy, finding the money to launch, expand or even just sustain a small business is often a struggle. In the second quarter of 2009, venture capital funds raised the smallest amount since the third quarter of 2003, according to the National Venture Capital Association in Arlington, Va. Banks continue to pull credit lines and credit cards from many small businesses. Even proprietors who are willing to extract capital from their homes -- often their biggest personal asset - can't always do so, because the declining housing market has left so many homeowners underwater.

But entrepreneurs are resourceful, and as the economic crisis forces them to seek new sources of capital, a growing number appear to be finding money in their own backyards. After all, local customers have a personal incentive to invest in their favorite businesses. And while no one is officially tracking the trend, anecdotal evidence suggests that the practice is growing.

"There are no secure returns out there right now," says David Lavinsky, co-founder of Growthink, a venture investment firm headquartered in Los Angeles. "People are very willing to invest in their local community, especially if there is the possibility of return."

In January 2009, Vox Pop, a popular bookstore and coffee shop in Brooklyn, was drowning in $190,000 of debt, including overdue rent, unpaid city health department fines and expenses from a failed expansion. Desperate, CFO Debi Ryan offered shares in Vox Pop for $50 apiece, calling community meetings and buttonholing patrons as they came through the door. Each share entitles its holder to a small dividend once Vox Pop's debt is paid.

In 10 days Ryan raised $64,000 from newly minted shareholders -- enough to keep the business afloat. With that capital came an unanticipated bonus: Vox Pop's customers-turned-shareholders visited the shop more frequently than they had before, coming in to buy everything from their morning coffee to children's birthday gifts.

"With this many shareholders we have a ready-made customer base," Ryan says. "Everyone wants to see Vox Pop succeed."

Lavinsky says Ryan's observation is spot-on. "When a customer is a shareholder or supporter, ego is involved," he explains. "If I give you a check for $5,000, I don't want you to fail."

Jeff and Tami VandenBerg, siblings who own the Meanwhile Bar in Grand Rapids, sold $5,000 worth of "Meanwhile Money" certificates as they were building their pub. That turned out to be a smart move. When they opened for business in 2007, certificate holders showed up in droves to spend their "money."

In the bar business, crowds beget crowds. They've never left. Says Tami: "It really brought a sense of community ownership to the bar. People felt vested in us."

For most small business owners, relying on the largesse of neighbors isn't a viable long-term survival strategy, but it can offer a shot in the arm during times of crisis or change. The VandenBergs, for example, used their community funding to install a tile floor and lighting while they waited for a bank loan to come through.

"In the big picture it was a small percentage of what we ultimately spent," says Jeff.

The largesse can be considerable. In April 2008, when Kim Harmson decided to open Kizuri, a fair-trade gift store in Spokane, she was able to raise $73,000 from 11 investors in the city's activist community at a low interest rate of 3%, with no prepayment penalty.

Harmson admits she had many sleepless nights before the store opened last October. She need not have worried. Since Kizuri's launch Harmson has met or exceeded sales projections every month -- an accomplishment she credits in part to her community-funded business model.

Consultants say honesty is the key to successful relationships with community patrons. As with any investor, a detailed business proposal should be offered, explaining why the funds are needed and what your benefactors will get in return.

"You don't want to come across as a fly-by-night person looking for a handout," cautions Warren Neuburger, the CEO of 40billion.com, a startup Web site that promotes community-based business fund-raising on social networking sites such as Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

And though it's essential to be candid, do your best to avoid sounding desperate. "As a business you never want to say 'I'm hurting,' " says Paul Gregory, a lawyer who specializes in small business issues with the New York City firm Herrick, Feinstein.

Larry Matthews, owner of Back Bay Grill in Portland, Maine, knew he had to install an air conditioning system in his restaurant to stay competitive. But amid deteriorating economic conditions he was reluctant to dip into cash reserves or to make a large purchase on credit. In June 2008, Matthews approached a group of his best customers, explained his need for cash and offered to sell them $1,500 restaurant gift certificates for $1,000 apiece. He raised the $12,000 he needed in one day.

Then he faced an unexpected issue: As word of the certificates spread through the community, customers who hadn't gotten a chance to buy them began calling. They wanted in on this great deal. Some were upset that Matthews hadn't sought their support. "I was surprised," he says. "People got a real kick out of the idea. They liked that I wasn't relying on a bank."

So Matthews, who also needed new dining room chairs, offered another round of certificates. This time he didn't turn anyone away. He raised $40,000, much more than he needed to pay for the dining room upgrade, and added the extra funds to his cash reserves. Matthews believes that the certificate program was a win-win. He was able to show his appreciation to loyal customers by saving them money without sacrificing his bottom line.

"If one or two tables a night use this credit, our cash flow isn't affected," he explains.

Even in this Great Recession, simply reminding people that local businesses need support can help stabilize them. The Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a Minneapolis research group, found that cities and towns that ran "buy local" campaigns during the 2008 holiday season saw retail sales fall by an average of only 3.2% from the year before, while towns that didn't sponsor such campaigns saw declines of 5.6%.

Sometimes the threat of losing a beloved merchant is enough to bring customers to the rescue. In 2005 the onslaught of big-box book retailers like Barnes & Noble (BKS, Fortune 500) and online providers, including Amazon.com (AMZN, Fortune 500), forced Clark Kepler to close his 50-year-old business, Kepler's Books, in Menlo Park, Calif. At the time he expected a few days of mourning among his regular customers and die-hard bibliophiles in the area.

Instead, distraught customers rallied in front of Kepler's shuttered store. They taped dozens of testimonial letters to his windows. More pragmatically, a number of well-to-do patrons reached out to Kepler, offering money and business expertise. Ultimately, Kepler's Books reorganized as a C corporation, with 24 community members contributing between $25,000 and $75,000 each to raise the $1 million necessary to reopen the store. These big-bucks benefactors are now shareholders, though Kepler admits they are unlikely ever to see a return on their investment apart from the satisfaction of helping to keep a much loved local institution afloat.

Not all of Kepler's fans could fork over huge wads of cash, but he didn't forget his smaller donors. With help from Anne Banta, a Silicon Valley public relations executive, Kepler devised a structure for donations modeled on museum memberships. Customers who donate between $20 and $2,500 are eligible for a variety of benefits, including discounted books and invitations to private author events. The store boasts 1,500 members who contribute, on average, $75 annually, providing Kepler with an extra $100,000 in yearly revenue.

To keep patrons happy and engaged, community-supported businesses must communicate with them efficiently. Vox Pop's Ryan set up an e-mail list that allows shareholders to contact her, other store employees and one another. Back Bay Grill's Website maintains a private sign-on area where account holders can monitor the amount of "money" they have left in the system. It's so successful, owner Matthews reports, that some of the restaurant's customers now pay for meals in advance, even though there's no longer a bonus offered for doing so. Why?

"They get to feel like rock stars," he says, laughing. "They can stand up at the end of a meal and walk away." ![]()

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More