A Kevlar killer comes to market

With help from the Pentagon, a carbon nanotubes innovator takes on DuPont.

|

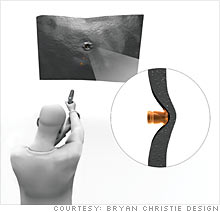

| Nanocomp's superstrong, lightweight textile survived its first bullet test. Each sheet is less than a fifth of an inch thick. |

(Fortune Small Business) -- Few entrepreneurs plan to shoot their product down. For David Lashmore, it was a necessity.

Lashmore's company, Nanocomp Technologies, is the first in the world to make sheets of carbon nanotubes -- microscopic tubes stronger than steel but lighter than plastic. The Pentagon has financed much of the Concord, N.H., firm's work; stakes include the $500 million U.S. market for body and vehicle armor, which is currently dominated by DuPont's Kevlar.

In April, Lashmore had a mechanical multicaliber gun shoot bullets at different versions of his sheet, each less than a fifth of an inch thick, at a speed of 1,400 feet per second. Four sheets were breached, but three showed no damage. Lashmore and his 35 employees were ecstatic.

"We didn't expect it to work at all," he admits.

Carbon nanotubes are not new. The superstrong molecules have excited scientists since the early 1990s. In theory, they could be used to build superlight cars or aircraft. But it proved difficult to grow nanotubes longer than 20 microns (one-fifth the width of a human hair). You could get the stuff only as a powder that was used to make tennis rackets and bicycles.

In 2003, Lashmore started experimenting with carbon nanotubes at a high-tech incubator. A year later he was making nanotubes 1,000 microns long.

That got the attention of Peter Antoinette, the former CEO of a high-tech materials company, and the pair founded Nanocomp in 2004. They developed a patent-pending system, controlled by a computer, that could produce large quantities of one-millimeter nanotubes. This was long enough to start making yarn and sheets.

More than 80% of Nanocomp's revenue, at least $10 million this year, comes from the Pentagon. "We're funding them more than we've ever funded any fiber project," says engineer Philip Cunniff at the Army's Research, Development and Engineering Center in Natick, Mass.

Army tests show the material works as well as Kevlar. The military also hopes to replace copper wiring in planes and satellites with highly conductive nanotubes, saving millions of dollars in fuel costs.

Within four years, Antoinette says, he will be producing the nanotube textile for upward of $10 per 35-gram sheet. The price of Kevlar varies wildly depending on the application, but Nanocomp will probably have to reduce costs to roughly $1 a sheet to be competitive. (DuPont makes 50,000 tons of Kevlar a year.)

Still, experts are optimistic. "They've solved a lot of problems," says Ray Baughman, director of the NanoTech Institute at the University of Texas at Dallas. "It's a relatively near-term product."

DuPont may soon have trouble shooting it down. ![]()

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More