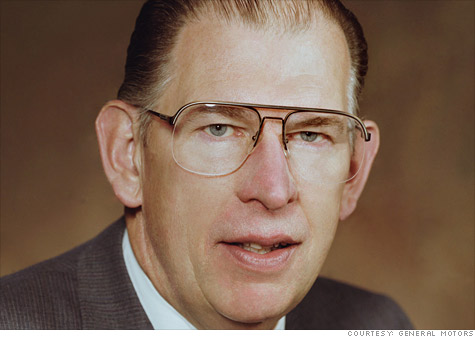

Former GM CEO Robert C. Stempel died at 77 on Tuesday.

FORTUNE -- Pushing out CEOs at General Motors has become routine lately, with two incumbents having been displaced in the past two years.

But when the board of directors got Bob Stempel's resignation in 1992, he became the first GM (GM, Fortune 500) boss to lose his job since company founder Billy Durant was removed in 1921.

He was the wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Stempel, an accomplished engineer and popular leader, was the kind of CEO GM had once needed, but his timing was bad. Stempel should have risen up in the 1960s when the automaker was being turned over to a faceless succession of accountants and bureaucrats. So accustomed were they to success that they allowed the car business to become secondary to the bureaucracy and insularity that would bring the company down in 2009.

Stempel, a car guy's car guy, might have prevented that. He loved working on things mechanical and was especially fond of the Olds Toronado, one of GM's first front-wheel drive cars.

Instead, he was forced to become a financial engineer. Stempel got his shot at the top job in 1990, after his predecessor Roger Smith spent the company's treasure on ill-considered ventures like armies of factory robots, unneeded assembly plants, and a whole new car division in Saturn.

Under ordinary circumstances, Stempel would have had a difficult time, given GM's competitive shortcomings. Market share had declined precipitously under Smith, falling from 43.5% to 33.5% and the company belatedly was cutting capacity to compensate.

Ever the loyalist, Stempel refused to undo Smith's disastrous decision to divide North American operations into two autonomous groups, thereby destroying the informal networks that actually allowed the giant company to function.

And he wouldn't get tough with the United Auto Workers, allowing the union to establish its notorious job banks that guaranteed laid-off workers nearly 95% of their full pay.

Stempel memorably referred to the contract as a "win-win" when it actually was a "win-lose."

Stempel's fate was sealed on his second day in office. That was when Iraq invaded Kuwait, setting off the first Gulf War, driving oil prices sky-high and sending the economy into recession.

Nothing in Stempel's engineering background had prepared him for this kind of multi-pronged crisis. The pressure was enormous and he didn't handle it well. A deliberate, perhaps plodding, decision-maker, he hated to be rushed into making changes and preferred to stick to his plan regardless of circumstances. And as a human being, he couldn't face the idea of laying off people he had worked with for years.

Procrastination at the top during a crisis antagonized the board of directors. Former Procter & Gamble (PG, Fortune 500) CEO John Smale was dispatched on a fact-finding mission that revealed a rot at the heart of the company.

When Smale reported back to the board in March, he didn't bring good news, as I recounted in Sixty to Zero, published this spring in soft-cover by Yale University Press. Costs were high, product quality was low, factories were running well below capacity, GM was slow to market, and a sweeping reorganization was needed.

Stempel reacted slowly, almost stubbornly, to the news. He ignored the board's direction to move two executives aside, and couldn't bring himself to dismiss a close friend, as the board wanted. Instead, he demoted him. Stempel remained in place as chairman and CEO, but had effectively been given a vote of no confidence.

The new setup didn't work. Reluctant as ever, Stempel didn't take the hints that rapid change was required and continued to proceed in his predictable manner. With the company hemorrhaging cash, the directors decided Stempel had to go, and on October 23, 1992, he did.

A proud man, Stempel stayed around Detroit. For a time, he penned notes to journalists -- something he would never have done as CEO -- correcting them on points of GM history. Then he went to work for a battery research company and waited years before the founder promoted him to CEO. Second acts are tough there, but Stempel was never heard to complain.

GM was lucky to have him in its good years. And Stempel was a loyal enough soldier to try to save it during its bad years. Unfortunately for him, and the company, he was badly miscast. ![]()