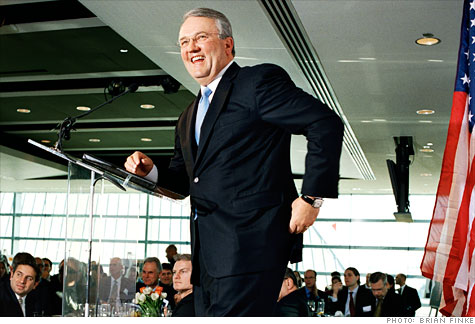

Lobbyist Jack Gerard

FORTUNE -- Jack Gerard has pretty much been in crisis mode since taking over as president and CEO of the American Petroleum Institute in November 2008. Shortly after he arrived at the powerful oil-industry lobbying group, President Obama and a wave of Democrats swept into office, promising to fund alternative energy sources and take action on climate change. Last year the BP disaster poured more than 200 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, and Gerard spent the summer prepping his members for more than 50 congressional hearings and eight separate investigations related to the spill and its aftermath. Then, in mid-May, executives from five oil companies appeared before a committee of the U.S. Senate and defended their earnings, which could hit record highs in 2011. "Don't punish our industry for doing its job well," Chevron (CVX, Fortune 500) CEO John Watson said. The performance was, by all accounts, a public relations disaster.

Indeed, Big Oil could scarcely be less popular than it is now: Gasoline prices on average are hovering around $4 a gallon, up more than a dollar from a year ago; turmoil in the Middle East and strong global demand contribute to high prices, but try telling that to the guy spending $75 to fill his tank at an Exxon station. President Obama, on the hunt for ways to cut debt, has targeted oil companies' tax breaks, and an NBC/Wall Street Journal poll in February found 74% of all respondents favor such a move. "Emotionally, no one is on their side," Robert Passikoff, president of the brand-loyalty consultancy Brand Keys, says of the industry. "No one feels bad for the oil companies."

And yet Gerard, a 53-year-old professional lobbyist whose last gig was running a chemical trade association, thinks he can get Americans to support, even root for, Big Oil. As he was putting out fires on Capitol Hill and at the White House, he also reached out to left-leaning groups that haven't been traditional allies, such as the AFL-CIO and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, and has even hired the Nature Conservancy's top grass-roots organizer to mobilize a citizen activism campaign for API. Gerard believes he can protect his industry by reminding an increasingly prickly and vocal public -- think Tea Party -- about how many people his members and affiliates employ. (API says it is responsible for supporting some 9.2 million jobs.)

Eventually he hopes to have a presence on the ground in every congressional district in the country, so when a policy proposal hits the industry's bottom line, lawmakers from Seattle to Savannah will hear complaints about it from voters back home. The gambit is showing signs of success. A series of API-organized rallies last summer helped derail the "spill bill" Democrats aimed to enact in the wake of the BP (BP) disaster. Now he is hoping the prospect of new jobs will stoke popular zeal for hydraulic fracking -- a practice that is raising safety and environmental concerns.

Wooing the American public is just one prong of Gerard's strategy for preserving his members' tax breaks and expanding their access to energy reserves. A lobbyist is only as good as his relationships, and Gerard, a devout churchgoer with eight children, including twin boys adopted from Guatemala, is quite adept at using his personal life to forge bonds with important allies on the Hill. At the same time he's gained unprecedented direct and regular access to the CEOs of his most important member companies, including Exxon's (XOM, Fortune 500) Rex Tillerson and ConocoPhillips' (COP, Fortune 500) James Mulva.

Gerard often seems clinical, almost professorial, when he talks about the issues he lobbies for. (He asks four times during one interview whether he is boring me, and in a follow-up session in his downtown Washington office he is surprisingly equivocal on the subject of climate change.) But rivals shouldn't mistake his professionalism for lack of passion. Gerard loves a challenge, and nothing could be more of a battle than revamping Big Oil's image. "If I'm playing basketball," the 5-foot-9 Gerard explains, "I want to take on the team who's got the 7-foot-3 guy as opposed to the team that's got the 6-foot-5 guy. Why? Because he's tougher to beat."

Making the right connections

Before Gerard agreed to take the job at API two years ago, he made an unusual stipulation for a trade association director. He didn't want to be just a hired gun; he wanted to be a strategic partner with a direct line to the industry's CEOs. He got it -- and he isn't shy about using it, keeping in constant contact with his bosses over the phone and by e-mail, much to the chagrin of the oil companies' in-house lobbyists, who don't enjoy the same access. "This can make or break a trade association, having that relationship at the top and having the ability to pick up the phone and talk to someone," he says. Gerard also regularly flies to Houston for meetings with oil executives, and he has found a way to get particularly close to Exxon's Tillerson, who heads API's biggest member company and happens to serve as national president of the Boy Scouts of America. Gerard has been active in the leadership of the D.C.-area organization.

"You sit down for dinner and start talking to somebody, and you find you've got a passion for something similar," Gerard says. "A remarkable thing about humanity is to come together and find those common bonds, and Scouts happens to be one I share with Rex." Tillerson credits Gerard with doing "an exceptional job leading the industry at a very challenging time" by assembling "an effective grass-roots and issue education program that has significantly increased the industry's voice in the national energy discussion."

Indeed, few of Gerard's good deeds go unexploited. He is an active presence in the Mormon church as the equivalent of an archbishop, which gives him ties to Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch -- the top GOP member of the Senate's tax-writing committee -- and presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Last summer Gerard joined Democratic Sen. Mary Landrieu and a U.S. delegation on a weeklong trip to London and Ethiopia that focused on international adoptions. Landrieu has always been a reliable friend to the oil industry -- Louisiana is one of the biggest oil-producing states -- but just two weeks after returning from her travels with Gerard she stunned the White House by placing a hold on Obama's nominee to be his next budget director, employing a Senate maneuver to block the appointment. Landrieu explained the move was intended to pressure the administration to lift the moratorium on drilling in the Gulf of Mexico imposed after the spill. The White House blasted Landrieu's ploy as "unwarranted and outrageous," but it relented, lifting the moratorium seven weeks before it was set to expire. Landrieu says the hold was her idea, and she asked Gerard to support her only after placing it. "I'm proud of it," she says, and as for the trip, "when Jack and I travel, we just talk about adoption issues."

Inside Gerard's head

The son of a John Deere salesman and a schoolteacher, Gerard grew up in Mud Lake, Idaho (pop. 358). As a child, he memorized the serial numbers on tractors while pitching in at his father's business. The family had a small farm too, and Gerard and his three brothers bracketed their school days by milking Holsteins. Back then there weren't a lot of distractions to complicate his schedule. Now Gerard chalks up his time-management strategy to a three-word formula: "good, better, best." It's a philosophy, he says, that encourages him not to settle for a good use of his time but to strive for the best one. The credo comes from a 2007 speech by a Mormon church leader named Dallin Oaks. Embedded in Oaks' message was an admonition that "to innovate does not necessarily mean to expand; very often it means to simplify."

And so Gerard has simplified API, firing 20% of the staff and paring priorities from a sprawling list of two dozen items, including research into alternative energy, to just six, focused on expanding onshore and offshore drilling and blocking proposals such as the Senate Democrats' effort to cut about $21 billion in tax breaks over 10 years. (Most of the money, almost $13 billion, would come from ending the oil giants' eligibility for a manufacturing tax credit, the rest from eliminating a number of smaller, industry-specific deductions.)

As instructive as the fights he picks are those he dodges. On the question of whether climate change is man-made, Gerard not only declines to offer an opinion, he's oblique on whether he has one at all. "I'm not a scientist," he shrugs. Gerard, who actually has been a part of this debate for a decade, going back to his days running the National Mining Association, doggedly steers the conversation to the process for addressing climate change rather than take a position on an issue that's core to his membership. "The view we've taken is that we have a committee that works on it." Asked if that includes a recognition that the phenomenon is man-made, Gerard weaves again: "I'd have to go back and look at the broader principles that have been adopted."

Gerard's rhetorical jujitsu on a hot-button topic dividing the parties -- and, to a certain extent, his membership -- speaks to a key piece of his mission. He has set about trying to change the perception that Big Oil and Republican politics are inextricably bound, a pursuit that gained urgency when Obama moved into the White House. Gerard acted quickly, hiring Marty Durbin, nephew of the No. 2 Senate Democrat, Dick Durbin of Illinois, to head up API's lobbying team and start opening Democratic doors on the Hill. He organized fly-in lobbying visits by African-American, Hispanic, and female oil workers. And he formed a partnership with the building and construction trades department of the AFL-CIO to tout the job-creating potential of new drilling projects. Informal talks with social-media experts from the Obama campaign prompted Gerard to poach Nature Conservancy's Deryck Spooner to help build a grass-roots army that now claims more than 500,000 members.

Last summer, after the House passed a tough bill to boost safety standards for offshore drilling and remove a liability cap for oil spills, Gerard mounted a round of rallies in regions far from the oilfields. At one, in suburban Chicago, more than 500 union workers assembled for a slick corporate production stage-managed to look like a working-class event. A parade of industry and labor leaders spoke, crediting the oil business for creating American jobs. The rally concluded with a speech by former Chicago Bears coach Mike Ditka, who blended stories of his own hardscrabble upbringing with an appeal for energy independence.

The protest -- one of seven that API organized last summer -- sufficiently spooked the Senate. "In those smaller media markets, it's a big deal," says retired Sen. George Voinovich, a moderate Ohio Republican. The spill bill barely got a second look when the Senate returned from its August recess. And when Obama in September proposed funding a new $50 billion infrastructure program by repealing Big Oil tax breaks, Voinovich told the President that the industry's on-the-ground vigor would be a major obstacle. Recalls Voinovich: "I told him, 'You've got as much chance as a snowball in hell.'"

The fight for fracking

Though API is seen as the lobbying arm of some of the world's largest companies (Exxon, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips are Nos. 2, 3, and 4, respectively, on the Fortune 500 ranking of companies by revenue), it also includes dozens of small suppliers, and Gerard has started to enlist those companies and other allies in his effort to show how vital the industry is to the economy.

During consideration of the spill bill last summer, API reminded liberal members of Congress of the small vendors that sell everything from boots to helicopter parts to the oil and gas business. Across the country farm bureaus, truckers, grocers, cattle growers, and union locals also got in on the act, piping up in defense of Big Oil. "Jack has done very well at expanding the allies we have in this so people understand how important we are to their industry," says Marathon Oil (MRO, Fortune 500) CEO Clarence Cazalot.

Gerard's tactics will soon be put to the test again as he tries to win local support for horizontal hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. The technique allows drillers to blast a high-pressure cocktail of water, sand, and chemicals into shale rock more than a mile underground. The process cracks the rock and releases the oil or natural gas trapped inside. Some environmentalists and local activists contend that runoff from the practice threatens to contaminate water supplies, a charge the industry denies. Blowback against fracking has been so intense in New York that the state declared a temporary moratorium pending further review. The Environmental Protection Agency is conducting its own study, with results expected next year. Gaining access to the deposits remains a critical priority for Gerard, and it's easy to understand why. Some of his biggest members -- including Exxon Mobil and Chevron -- have been getting in on the frenzy by snapping up smaller outfits working in the field. For Gerard, developing the new resources could be a political game changer for the industry, allowing it to ramp up its presence far beyond the traditional confines of oil-rich and gulf states. The largest known oil shale deposit in the world sits underneath Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah -- containing an estimated 800 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Another major deposit spans most of North Dakota, into Montana. The Marcellus Shale, containing the largest natural-gas deposit on the continent, underlies New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. And a sizable deposit, the Fayetteville Shale, is buried in northern Arkansas. Gerard touts the employment benefits of starting projects across the map -- 280,000 new jobs over the next decade by developing the Marcellus Shale alone, and another 340,000 by building the Keystone XL pipeline, a 1,700-mile venture to carry crude from the oil sands of western Canada down to Texas Gulf Coast refineries. All are potential enlistees for Gerard's grass-roots army. But it turns out that highly paid oil executives aren't the only potential liabilities to Gerard's efforts to put a kinder, gentler face on the industry. As the rally in Joliet wound down, attendee Mike Dalfano, a pipefitting instructor, acknowledged his enthusiasm for the Keystone XL pipeline and the jobs it would create, but he isn't ready to give Big Oil the tax breaks and perks Gerard is seeking to preserve. "The oil companies are profiting quite a bit, and we need to tighten the screws on them." Presented with Dalfano's ambivalence toward the industry that supports his job, Gerard is nonplussed. He's convinced that Dalfano and millions of others will come around. "We're putting the true human face on this industry, so people understand these are moms and dads, local PTA presidents, and Little League coaches," he says. "That's our challenge. And when the public understands the consequences, they weigh in." Now if only his biggest members could just stay out of the headlines. ![]()